Designing I-Docs for the Classroom

By Liz Miller

Over the last several years at festivals, conferences or even faculty meetings I hear a familiar refrain, “Who exactly is the audience for interactives?” Many film festivals are still figuring out how to properly program i-docs so that they don’t end up in neglected corners, as side-shows to other main features. Directors have been exploring a wide range of methods to get users to move beyond a cursory visit and dig deep into what is often a great deal of content.

As a professor and documentary maker with experience in media advocacy I see media as a first step in a longer process of social engagement. I am as invested in the outreach stage of a project as I am in the production. What really matters to me is how interactives can be used and circulated to make a difference. What can an interactive do that another media form cannot?

How to engage students with i-docs

As a professor of Communication Studies in Montreal, I spend a lot of time in classrooms and I use interactives as primary texts, so, of course, I have a bias, but I do believe that one of the crucial places where interactives really matter is in the classroom, and here are a few reasons:

- The luxury of time: One of the biggest challenges for interactives is maintaining attention in a crowded mediasphere where viewers can click away. If an interactive project has two to six hours of material and users spend an average of seven-minutes on a project, that is a pretty unfulfilling viewing ratio. Since academic semesters usually run from ten to thirteen weeks, classrooms can offer a more immersive experience, where students can engage with a project over time.

- Digestibility: Educators have been showing short clips of feature-length documentaries in the classroom for years. There just isn’t time to show a 90-minute piece. Most interactives are already a composite of easily digestible micro-pieces, making it easy to share with students.

- Different learning styles: By integrating maps, data-sets, video, images, text and more, interactives make it easy to talk about new forms of literacy. Medical students are now using videos and streaming media alongside text books to learn about open-heart surgery or other complex procedures. Likewise, an interactive can be paired with a theoretical article, a podcast, a collection of tweets, or any other media.

- Multiple perspectives: A collaborative, non-linear form offers a welcome alternative to the exceptionalism of the single protagonist and puts diverse perspectives into conversation. The polyvocality of many interactives works well in a classroom, where students are asked to consider comparative perspectives, frames of references, and situated experiences.

- A captive audience: Despite the fact that digital natives are the obvious target audience for interactives, my experience is that very few students or teachers are discovering them on their own and the classroom is an obvious place to introduce them.

With all of these advantages, I wanted to explore how I might design an environmental interactive for the classroom. Many of the environmental activists I work with suggest that the most effective way to address thorny environmental issues is through education. I wanted to make teachers like myself the target audience and see how that would impact the development, the aesthetics and even my own perspective on advocacy, education and outreach strategies.

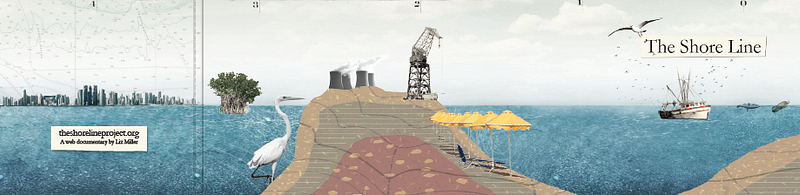

So in 2014 I began working on The Shore Line, a storybook for a sustainable future designed by Helios Design Lab.

Who to turn to for models?

I started the project by researching what was already happening with interactive outreach. I first spoke to the directors and outreach coordinators of three high profile Canadian interactive projects: Here at Home, Fort McMoney, and Highrise. These conversations led to some key insights that I discuss in greater depth in an article I co-authored, “Choreographies of Collaboration: Social Engagement in Interactive Documentaries.” But here are a few key points:

- Long-term partners who have a mutual stake in an interactive project play a critical role in ensuring its potential to make a difference. Considering how a project will be used from the outset will inevitably broaden the potential reach. And impact should not be conflated with exposure since getting a project to the right audience can be more effective than trying to reach everyone.

- Media partners are key in getting broad attention for a project. Media institutions such asThe New York Times, The Globe and Mail, and The Atlantic have been exploring partnerships with interactive directors to garner attention around contemporary issues. This model can be applied to smaller media outlets as well to reach more targeted audiences.

- Guides. It is easy to miss out on key features in a crowded mediasphere so having a dedicated person to help users navigate the site and to seed debate is critical for an interactive to remain relevant for more than the average seven-minute session.

Through these conversations I learned a great deal about the emergent roles of “game masters,” “super players,” “matchers” and more, but I still felt that the classroom as a targeted site was lost in the quest for mass exposure. This is not to undermine the tremendous work of projects such as Campus, the National Film Board’s five-star educational resource, or the stellar educational guides that projects like Highrise have developed. But it just seemed to me that if teachers were somehow invited in as partners early on, there might be a way to build a deeper impact.

Another approach was to see what practitioners from diverse disciplines were doing to make their work matter. Together with Steven High, an oral historian, and Edward Little, a theatre artist, I conducted over thirty interviews with artists and scholars who were invested in the social impact of their creative work. Our main take-away was that there are few shortcuts in making cross-disciplinary projects matter. Social impact takes time and solid partnerships are essential. The interviews we conducted are featured on a website, Going Public, and in our upcoming book, Going Public: The Art of Participatory Practice.

Finally, I returned to case studies of long-format environmental documentaries that were made with the intention of shifting public perspectives and practices. Shirley Roburn’s thoughtful essay “Beyond Film Impact Assessment: Being Caribou Community Screenings as Activist Training Grounds” carefully analyzes the long-term advocacy strategy of the film Being Caribou and deconstructs simplified notions of social engagement. Also, Beautiful Solutions is an elegant internet resource companion to Naomi Klein’s environmental documentary This Changes Everything that I have found especially useful in the classroom.

Shore Line: Liz Miller & Helios

Design Labs

Shore Line: Liz Miller & Helios

Design LabsPutting it all into practice

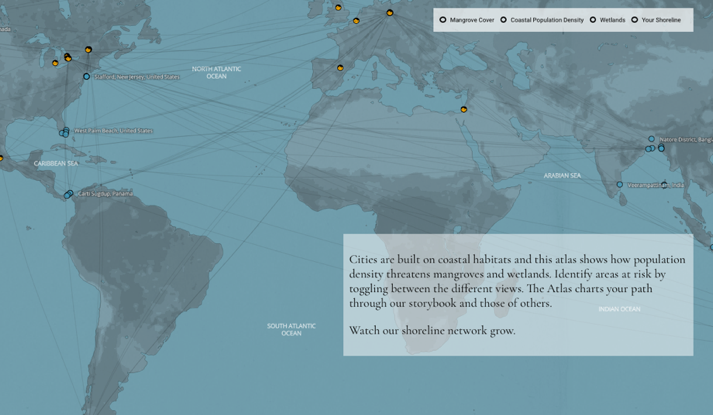

The Shore Line is about the dramatic changes playing out along our global coasts. I was drawn to the coast as a subject, but also as a metaphor and even a method — as a way to challenge boundaries and narratives in addressing climate-disasters. The surge of coastal tourism, the increased dumping of industrial waste, and the unsustainable growth of fossil fuels are threatening the very ecosystems that protect us from increasingly frequent storms and sea level rise.

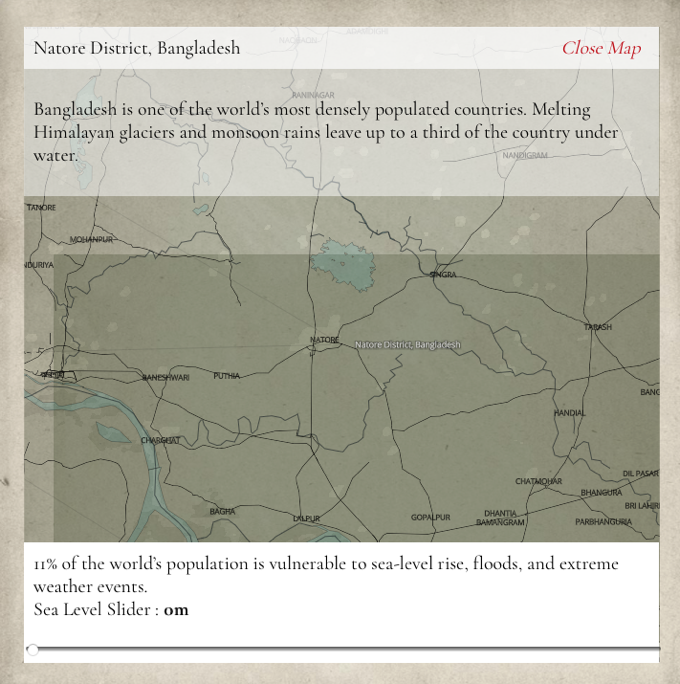

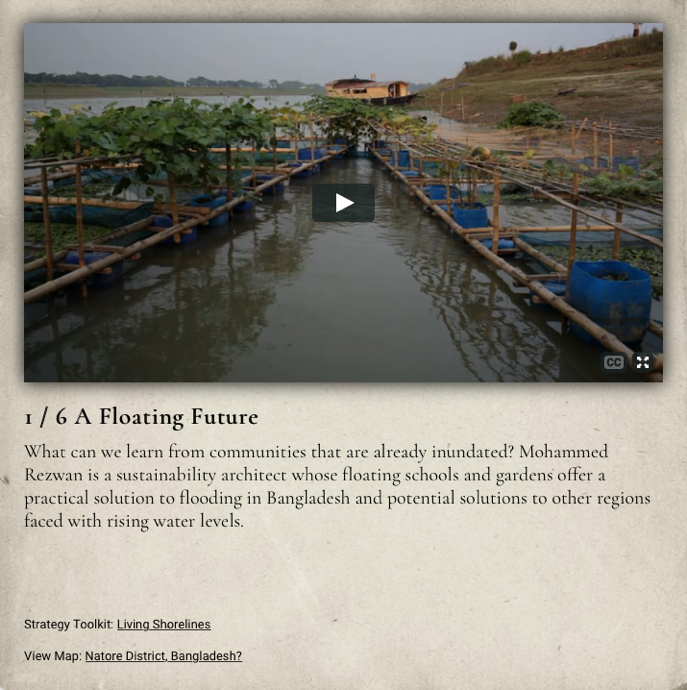

Rather than dwell on disaster, however, the project features 43 profiles of individuals enacting change along the coast. Our team consisted of international documentary directors, students, educational advisors, and Helios Design Lab. The project features a sustainability architect in Bangladesh who designs floating schools, a sand artist in New Zealand, an Indigenous community organizer in Panama who is coordinating the migration of his village from a low-lying island to the mainland, a science fiction writer in Vancouver, and a wide range of people who are out there making a difference. Each of the 43 profiles is connected to a map with a sea level slider to visualize that community with up to six meters of sea-level rise.

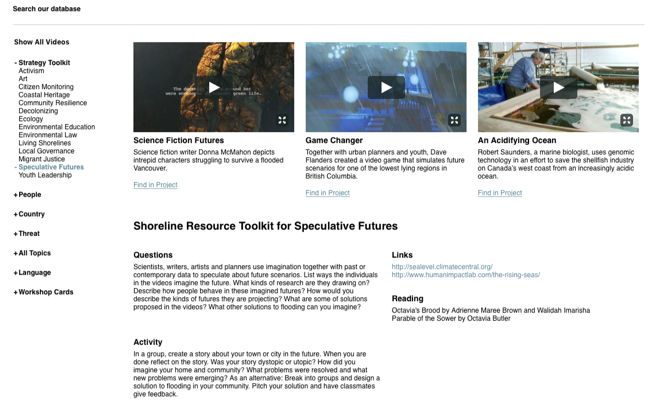

Our atlas features all the video profiles alongside NASA data sets to visualize the impacts of coastal population density and development on existing wetlands and mangroves. And in the database we have strategic toolkits with action-based pedagogical resources.

I teach a course in media and the environment and one of the biggest issues students express is being overwhelmed by the scale of environmental destruction. Glenn Albrecht, a philosopher and professor of sustainability at Murdoch University in Perth, has coined the term “solastalgia” to describe the profound sadness we feel knowing that the landscapes that we love are under attack.

Albrecht came up with the term as the coal industry in South East Australia was turning the coastal city of Newcastle into the largest coal-exporting port in the world. People were writing to him in desperation as the landscape disappeared before them. I wanted to create a resource that featured achievable actions — a place where students could discuss how place, traditions, gender, race, age and economic circumstances inform local methods of resistance or resilience. Below are a few ways I approached the challenge.

- Identify teachers to profile: With teachers as a target audience, I intentionally wanted to find some exceptional teachers to profile. We developed five profiles of educators from India, the U.S, and Canada who are helping their students feel connected to the environments around them and who are helping students initiate actions and campaigns. We also feature youth educators (ages 13 to 23) who, with the support of mentors, are holding workshops with adults, planting mangroves in sinking communities, and learning about laws and treaties in order to defend their land.

- Create integrated toolkits and resources: Teachers spend about 30-seconds reviewing a new resource and so, in consultation with a seasoned educational trainer, we developed one-page workshop sheets for easy use in the classroom. I asked graduate students, environmental experts and experienced teachers to author one-page workshop sheets and to design questions, activities, and resources that we could also feature in our online “strategy toolkits.”

- Test the project in classrooms: An early first step was to test out the project with my students. For a graduate seminar on media and the environment, I had the students watch four short videos each week, paired with articles we were reading. They were asked to write weekly responses on a website we developed for the class. The best part of this exercise was the ritual of writing and the challenge of synthesizing dense articles with the short videos. With my undergraduate production class I sent eight production teams to different shoreline sites around the island of Montreal as part of a place-based observational exercise. By visiting, observing, and documenting their own shoreline, the students had a more informed starting point for analyzing the site and the challenges of other shoreline communities.

- Design the project to reach across platforms and cultures: It is no secret that designing a project that would work in classrooms from Bangladesh to Canada is an enormous challenge. We have had to make numerous decisions in order to balance the excitement of what we could do with the reality that most teachers work with technological constraints.

The project is online and we are planning an official launch at the end of October in connection with Sustainability Day. I am excited to send the project out into classrooms but it will take a lot of work. I can already see how critical is to sit down with teachers and show them all the features we have developed over the last year. Despite my best intentions with toolkits and resources, every teacher has a different screen, a different platform and a different relationship to technology. And there is a lot more to figure out to make this interactive matter.

Meanwhile, Glenn Albrecht has come up with a new concept, soliphilia, which he describes as “the love of and responsibility for a place, bioregion, planet and the unity of interrelated interests within it.” Hopefully The Shore Line is one small part of a desperately needed effort to foster inter-connections with each other and with the ecosystems we rely on.

Further reading:

- Sandy Storyline

- Great Lakes commons map

- Indigenous Environmental Network

- ‘Surfacing’ project

- The Beach Builders by John Seabrook

- The Beach, A Fantasy by Michael Taussig, 2000

- The Human Shore by John Gillis

- The Great Derangement, Climate Change and the Unthinkable by Amitav Ghosh

Liz Miller is an independent documentary maker, trans-media artist, and professor who lived in Central and South America for over six years. She is committed to producing work that connects individuals across cultures. She is interested in new approaches to community collaborations and the documentary format and her work connects personal stories to larger social concerns. Find out more.

This piece appears in issue #10 of Immerse, which was curated by the editors of i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary (Columbia University Press, 2017). Discover other stories in this issue here.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.