Cases in Search of Uses and Vice Versa

This is the first installment of a new column by Immerse editor Jessica Clark, “Interface Everywhere,” exploring the implications of storytelling and art at the cusp of the physical and the digital.

VEGAS— Up and down the strip, towering screens tout performers and pasta, mobile billboards boast intricate acrobat automata, a sultry pair of eyes surveils you from a rooftop, and in every direction, flashing, blinging lights lure cash out of your pockets. Reality and simulation mingle freely: a fake Eiffel tower cheek-to-jowl with a strangely spangly CVS. The mind reels.

Vegas

itself is a disturbingly immersive experience. Photo by Jessica Clark

Vegas

itself is a disturbingly immersive experience. Photo by Jessica ClarkSo, what could be a more fitting, immersive setting for the Consumer Electronics Show (CES), the massive annual extravaganza of gadgets and gizmos? Engulfed by The Venetian — itself a hi-fi replica of a tourist phantasm — I strap on my badge, bag, and water bottle and trek to what’s called “Eureka Park.”

There, I find a section of scrappy startup vendors busy eroding the boundaries between the physical and the digital. Drone racers from Croatia explain that their 360 headset offers a more encompassing first-person view, allowing “you to fly 150 miles per hour with your feet on the ground.” A maker of tactile data gloves allows me to pick up, plant, and water virtual seeds. I drool nostalgically over the Pix backpack, which displays a programmable animation reminiscent of a Lite-Brite, and the Cinema Snowglobe. A video clip plays when you shake one of these, explains co-founder JD Beltran—like a digital picture frame with a “a better, cooler form-factor.” Even cooler: a larger “crystal ball” version.

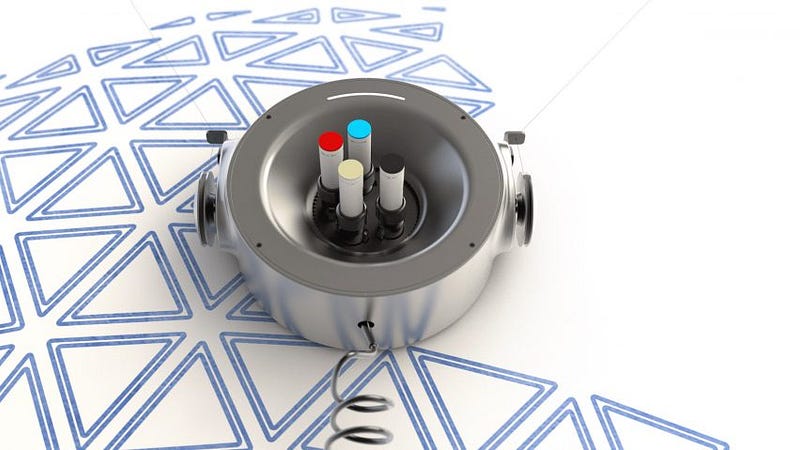

The Scribit

is suspended on a wire between two nails, and wanders your walls drawing images that you

program.

The Scribit

is suspended on a wire between two nails, and wanders your walls drawing images that you

program.Scribit combines analog and digital elements in a new way: plotting out a drawing on a wall with custom markers that allow images to easily be written and erased. “Scribit is our response to the fact that today’s innovations are all bringing in more pixels, more stress, more information into our lives,” said Chief Marketing Officier Andrea Baldereschi. “We liked the idea of creating a piece of technology to remind us that beauty takes time to be achieved and take shape.” Easy to set up with just two nails and an outlet, this “write and erase robot” is designed to be used in homes, businesses, and educational settings. Multiple Scribits around the world can be programmed to draw the same picture simultaneously to facilitate collaboration or team building.

Few of the vendors I spoke with had thought about storytelling or journalism applications for their products. Instead, they see “use cases” for more lucrative industries—telemedicine, defense, flight simulators, driverless transport, advertising.

How would a filmmaker or journalist use data gloves? “That’s an interesting question,” reflected Maxime Stinnett of BeBop Sensors, the motto of which is “Make Things Knowable.” Perhaps it could be used to control documentary drones, he suggested, or for haptic reporting, in which the user could feel the thing being described. “We haven’t thought about it yet, to be honest,” said Ivan Jelusic of VR headset maker Orqa FPV, “but I’m very much sure that some smart people can come up with applications for that.”

My suggestion that the Pix backpack could be used as a roving news ticker was a new one—hard but not impossible given that you program the animations one at a time from a related app. “All of the best ideas are in your mind, not mine,” said Baldereschi—a refrain which suggests a wide open field for documentarians and other creators of nonfiction narrative to seize upon emerging tools and find compelling uses for them.

For me, a clear takeaway from CES is that the “user interface” as it is commonly understood has officially exploded. No longer limited to an interaction on a screen or with a joystick, the connections between humans and machines have moved both out into the world and more intimately inside the body.

Of course, there were numerous screens of all sizes on display (including the much-anticipated foldable ones)—as well as eye-popping holographic displays such as Hypervsn—see my interview here. But this year, with flagging headset sales, buzz about VR was on the wane, and AR/mixed/extended reality was on the rise.

Image

courtesy of Nreal.

Image

courtesy of Nreal.For storytellers, this presents interesting interface challenges, as whatever is being superimposed upon the world around the viewer has to blend well with the background. When I tried the Nreal Light —a pioneering mixed reality headset that looks and feels like regular sunglasses—the 3D images were impressive but made little sense superimposed on passing conference-goers. Complete with prescription lenses for users that need them, these take a big step towards making augmented reality more consumer-friendly. But again, this is a case in search of a better use.

AstroReality’s info about the moon is regularly updated with data from NASA,

USGS, SETI and other sources.

AstroReality’s info about the moon is regularly updated with data from NASA,

USGS, SETI and other sources.One nice example of form, content, and function melding intelligently was AstroReality’s AR moon, earth and planets, which allow users to hold a 3D-printed model of a celestial body and zoom into it with an app to get related information backed up by data from NASA. How and where this might be used was clear: in classrooms, planetariums, and the homes of astronomy enthusiasts, in the same way globes were in our not-so-distant past. The companion AR notebook adds a fun Harry Potter-style taste of the experience for people who can’t afford the models themselves. (Full disclosure—they gave me a free one since I was there covering CES. See the demo here.)

If mixed reality breaks the fourth wall between the viewer and the experience in new ways, some gadgets on display at CES breach previously sacrosanct boundaries between bodies and machines. Healium XR uses a “brain sensing headband” in conjunction with an app or VR googles to track users’ stress levels and prompt them to more sanguine states while watching “therapeutic stories” that they can influence with real-time EEG feedback. The Dreem band also tracks brain activity, plus movement and heart rate, to monitor sleep quality and pipe sleep-inducing tracks into your inner ear via bone conduction. Sounds relaxing.

Is your

fetus ready for a close-up? Photo by Jessica Clark

Is your

fetus ready for a close-up? Photo by Jessica ClarkThe Fetus Camera allows moms-to-be to snap their own in-utero candids of the “first smile of life,” while the Pregnancy+ app offers eerily interactive images for each stage of gestation. (Strangely enough, pregnancy’s fine, but female pleasure is off the table.) At CES, it seems that practically anything on a human can become an interface: your skin, your jewelry, your shoes. No more just buying a shirt and wearing it—geotagged garments from Awear Solutions gather info about when and how a garment is worn, and connect to a scavenger hunt game which rewards you for wearing it to particular locations.

While such new possibilities offer exciting creative options for storytellers, it’s all a bit overwhelming. After traipsing through several exhibit halls on my first day at CES, I retreated to a readymade immersive environment: the Dream Box, which promised to balm my nerves with chromotherapy and an enclosed nap space. By day two, I retreated to yet another simulation—the Salt Grotto in the Venetian’s Canyon Ranch Spa, complete with soothing “sea air” (Quote marks are theirs) and ersatz twinkling stars. By day three, I was good and ready to flee Vegas for the nearby Mojave Desert with its actual rocks and sky.

Palate

cleanser: immersion 1.0 in the Mojave. Photo by Jessica Clark.

Palate

cleanser: immersion 1.0 in the Mojave. Photo by Jessica Clark.A month later, in Park City, it was a relief to return to the New Frontiers exhibition, where the tech was at least peripherally being put to use in service of stories and art. There I saw an old soliloquy reborn in Seven Ages of Man, a volumetric capture of an actor performing Shakespeare’s famous speech from As You Like It, which aptly observes that “all the world’s a stage.” The piece, experienced via a Magic Leap AR headset, allows viewers to walk around a 3D figure of the actor, blended with CGI animation, and a physical set. At this point the tech is relatively seamless, enough so that it’s possible to concentrate on the content rather than just the novelty of the experience.

“We’re here at Sundance to share how theater and this world are colliding, and how we look at performance in new ways,” said Sarah Ellis, the director of digital development at the Royal Shakespeare Company. The hope is that by making such immersive experiences available anywhere, audiences won’t be disenfranchised by their location. “It’s how we extend theater into to the multiple stages we have today.” The process involves not just new tools but “new craft,” she says—a mixed reality device allows audience members to see one another, recreating the communal experience of live performance.

Sitting in a booth at Ben’s Chili

Bowl with Samaria Rice. Photo courtesy of Oculus.

Sitting in a booth at Ben’s Chili

Bowl with Samaria Rice. Photo courtesy of Oculus.Another strong piece in the New Frontier exhibition that combined physical and digital elements was Traveling While Black. Participants sat down inside a a recreation of a booth in DC-based restaurant Ben’s Chili Bowl to experience VR conversations with locals and civil rights activists set in a similar booth. The feeling of being there in the scene was palpable, and the discussions were bracing, reflecting on historical and contemporary prejudice.

During one conversation with Samaria Rice—the mother of Tamir Rice, shot in Cleveland in 2014—the restaurant’s patrons form a circle around the booth, serving as witnesses. Coproducer Ayesha Nadarajah explained that the team came up with that idea for the scene the day they were filming. “We wanted her to feel that she was surrounded by a supportive community. She said the presence of those people made her feel safe.” Because the experience can be intense, the team created the setting of the booths to give participants their own safe space to reflect and recover. A 360 version of the film is available from the New York Times, but the sense of being inside of it is hard to match.

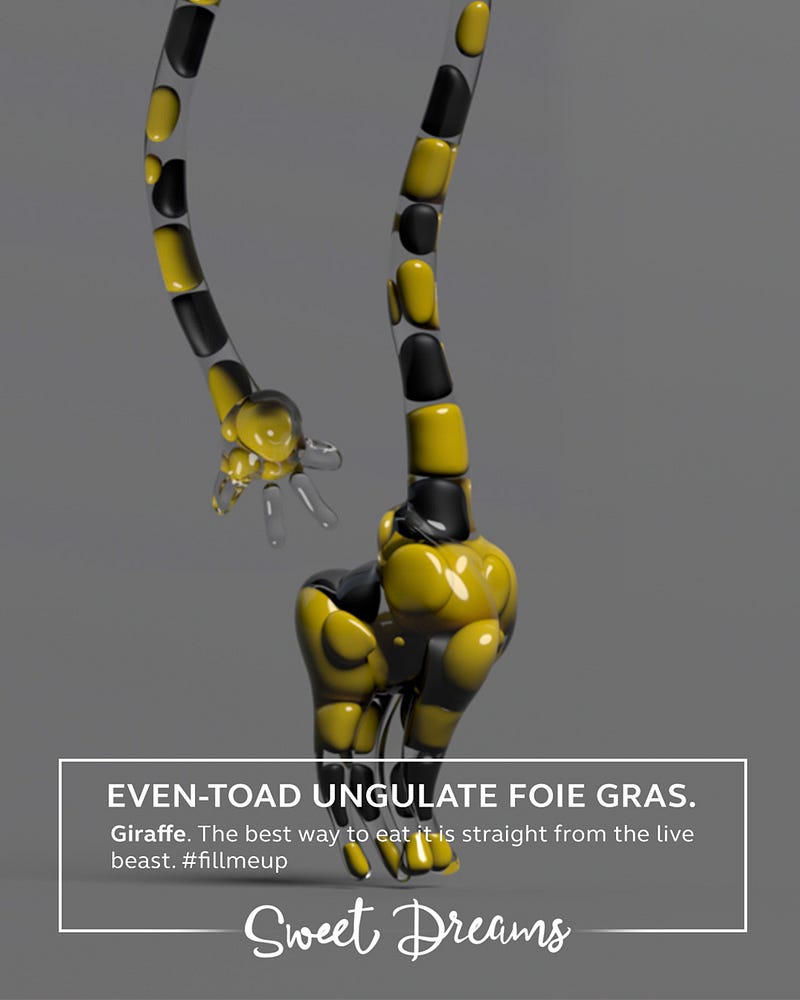

Other pieces were less serious, but still intriguing. One favorite: Sweet Dreams, by Marshmallow Laser Feast, offered a whimsical morality tale about gluttony set in Luscious Delicious Land—a place where people get so greedy, they end up consuming the universe itself. Throughout the experience participants are asked to taste various items while wearing a VR headset, and the tingly, tart, surprising flavors are almost distracting enough to counter the fact that much of the story is set at the teetering edge of a giant gullet.

What would it take to bring some of this—history, heart, prankster creativity—to the seemingly soulless halls of CES? There’s surely some sweet cash to be made in improving the user interfaces for insane all-you-can-gorge tech shows. But that’s a challenge for another column.

Photo (banner): Michio Morimoto

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.