Have you ever met a normal, healthy and working engineer who gives a damn about contemporary art?—Billy Klüver, founder of E.A.T.

The clashing worlds of art and science make strange bedfellows — or so it might seem. But a rendezvous between this unlikely twosome leaves plenty of room for ramifications. Yes, artists and scientists ask different questions, use different methodologies, and pick different platforms and modes of communication to share their findings. Their positions in society are poles apart. Despite these differences, over the past decades, joint ventures marrying art and science have grown into a fascinating field of their own.

Multiplicity and diversity are key. Such projects don’t come in one flavor: They have an agile and iterative nature, and they take on different shapes and forms. Such collaborations are part of the creative and cultural industries— which are the topic of a one-year research project I am working on in the context of the Creative Economy theme of the Fontys University of Applied Sciences in Eindhoven, in collaboration with the Amsterdam based design studio ARK .

Under the title Our Brave New World, this research encompasses a field in which both a critical as well as a curious attitude towards technology is felt. The title refers to the science-fiction novel Brave New World, written in 1931 by Aldous Huxley, in which a dystopian future is dominated by technology and rationalism.

To counter this, Our Brave New World is an investigation into how the creative and cultural industries re-appropriate our technology-driven society and work to unpack how in an active, creative and responsible way, new possible futures are being researched and developed. Our Brave New world wants to investigate the various technical, philosophical, ethical, and mind-expanding questions arising at the intersection of art, science, technology, society, and the future.

This research project describes an intricate maze of cross-disciplinary labs as artistic practice. These operate just beneath the surface of the everyday world but together are shaping the cultural, social, and political possibilities of tomorrow. How can the creative industries be framed as a blueprint for our possible futures? And, more importantly, how can we keep track of their findings to give change a kick in the tail?

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). Mirror Dome Room at the Pepsi

Pavilion, at Expo ’70, Osaka, Japan

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). Mirror Dome Room at the Pepsi

Pavilion, at Expo ’70, Osaka, JapanIn his Two Cultures lecture in the 1950s, chemist and novelist C.P. Snow talked about a “gulf of mutual incomprehension” between literary intellectuals and physical scientists. This gap was the reason it was so hard to solve the world’s problems, he said. Now, 60 years on, the compatibility between Shakespeare and the second law of thermodynamics still can’t be taken for granted, and still holds a world of promise.

Bell Labs was one of the first interdisciplinary labs to bring its findings to a broader audience. Under the direction of John Pierce — perhaps not coincidentally also a science-fiction writer and author of the article “Portrait of the Machine as a Young Artist” published in Playboy in 1965 — Bell developed technologies such as the transistor, laser, Unix, C, and C ++, followed by computer graphics and computer animation. It was Pierce who in 1961 invited artists such as James Tenney, Stan Vanderbeek, and Lillian Schwartz to join his scientific team temporarily as artists-in-residence.

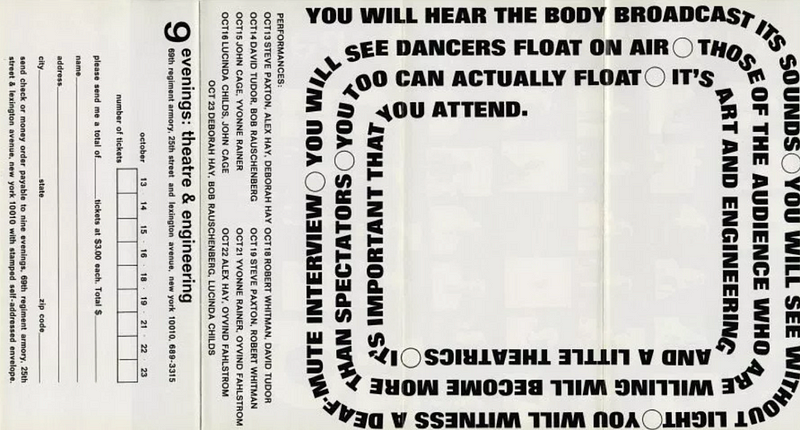

In a follow-up, Bell Lab’s Billy Klüver oversaw the production of the now famous 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering in New York in 1966, which would later become Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). The goal was pretty straightforward: to investigate whether it was possible to bring these disciplines together. Tasked with this mission, 10 artists and 30 Bell Labs engineers went to work for 10 months. And they certainly put on a show worth watching. Although the 9 Evenings were not always received positively by critics — not everything worked, and technical and artistic characteristics became confused — they succeeded in sparking the audience’s imagination about such collaborations between art and science.

When your

event’s promotional poster promises that, for a mere $3 a ticket, “You will hear the body

broadcast its sounds * You will see without light * You will see dancers float on air” and

concludes with “It’s Important That You Attend, there’s bound to be some disappointment.” —

Patrick McCray, Leaping Robot Blog (http://www.patrickmccray.com/tag/billy-kluver/)

When your

event’s promotional poster promises that, for a mere $3 a ticket, “You will hear the body

broadcast its sounds * You will see without light * You will see dancers float on air” and

concludes with “It’s Important That You Attend, there’s bound to be some disappointment.” —

Patrick McCray, Leaping Robot Blog (http://www.patrickmccray.com/tag/billy-kluver/)

The objective of E.A.T. was, in Klüver’s words, to make “materials, technology, and engineering available to any contemporary artist.” In its heyday E.A.T. had 28 divisions in the U.S. with more than 6,000 members.

As we can also read in the recently published M.I.T. research project Collective Wisdom—a vast endeavor by Kat Cizek, William Uricchio and others — and also published in parts here on Immerse — joint lab practices have gained importance and have been further developed since E.A.T. This is not only as a new form of creating and sharing knowledge within the cultural and artistic domain, but also as a challenge to the idea that work has only one creator, one author. Why do we see these new and flexible forms of collaboration, organization, creation, and authorship popping up today, not only organized top-down by the “established” organizations, but also as a new mode of rhizome-like initiatives, sparked by individuals?

© 2015

Xandra van der Eijk, BAD AWARDS, Fluid Matters

© 2015

Xandra van der Eijk, BAD AWARDS, Fluid MattersThe reason could be that we, as a planet, are facing a series of interrelated problems that are too complicated to deal with from within one discipline, or even one country or one political entity: technology, ecology. As a central element, we, humanity, are getting in each other’s way, and we need all the help we can get to cope with the aftermath.

Another reason could be that technological networks seem to have enveloped almost every aspect of social and personal life, turning users into products, as Shoshana Zuboff puts it in her recent book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. The question is, how can we push back?

In the future that the surveillance capitalism prepares for us, my will and yours threaten the flow of surveillance revenues. Its aim is not to destroy us but simply to author us and to profit from that authorship.—Shoshanna Zuboff, 2019

What’s more, wearable, and wireless technologies have the strange quality of being both omnipresent and invisible at the same time. Like fish, we are unaware of the water that keeps us alive. Technology is becoming increasingly opaque and most of us are oblivious to the ethics and politics of algorithms and data trackers, yet undeniably they steer our choices, leaving us to wonder who is boss.

At the same time, we have entered a new age at an ecological level: the Anthropocene. The impact of human life on the planet is undeniable and irreversible. Here we are entangled in a catch-22: it’s partly technology that got us into this mess, and it seems that it’s also technology that’s going to get us out of it.

But maybe there is a third way, and we should be heeding Evegeny Morozov’s warning about “solutionism”: the false notion that as long as we use the right code, algorithms, and robots, we can make the world frictionless and trouble-free. The value of imperfections and the necessity of looking for alternative roads is crucial. We need to come up with different solutions: social, analog, political, and creative. Do we need better tech? Or do we need better humans? Or are the two interconnected? Negotiating these questions is critical in understanding our world of today and tomorrow.

As Néstor García said in Art Beyond Itself, art can help us out: “It can be the place of imminence, where we catch sight of things that are just at the point of occurring; it proclaims something that could happen, promising meaning or modifying meaning through insulation.” But art alone is not enough to respond to our increasingly complex environments; multi-disciplinary skillsets are necessary to unravel old domains and build new ones, and to explore new frontiers. We need unusual but fruitful collaborations between different disciplines to face the music: artists and engineers, storytellers and creative technologists, and thinkers and doers will come up with new approaches for alternative futures.

The research we are embarking on will reveal the collaborations of these sorts of teams, of artists and storytellers, philosophers and dreamers, scientists and coders, technologists and filmmakers, and will show how, beyond the dystopian and utopian narratives, they are creating new stories for and about possible futures. It is about groups that operate in the intriguing domain where the triangle of a) art, science, and technology, b) society and c) the future compete to take the foreground.

The primary motivations are shared interests and curiosity. The process is as interesting as the outcome, and serendipity is a shared practice. A fascinating set of organizations is arising — made up of interdisciplinary bio-labs, media labs, meet-ups, and pop-up organizations, sometimes governmentally fostered and funded and sometimes fully independent and bottom-up, grassroots and activist-minded.

Research

ARK: examples of interesting data visualizations by a.o. Clever Franke

Research

ARK: examples of interesting data visualizations by a.o. Clever FrankeThis mesmerizing and scattered collection of interconnected initiatives is not that easy to find, and it is primarily an inner circle of fanboys and girls that keeps track of their comings and goings. There is not something like a yellow pages of the creative industries divided into clear categories where we can look them all up.

This is a total missed opportunity for many reasons: for the field itself it would be great to have an easy way to team up with like-minded organizations to share ideas and compare notes, or to be able to look up someone from a different domain — beyond your own network — and to find new partners in crime. But also for possible new audiences, curators, decision makers and governments it would be an improvement to have a place to go if you’re looking for the latest developments in these cultural and creative industries. So, how can we make this mostly invisible grid of initiatives show up on the surface of our awareness, and make sure we can find them when we need them, so their labor and adventures will be shared with a wider community than their own address book?

We will be working with the graphic design collective ARK on an interactive map of the creative industries in the Netherlands. So far, we have built a list of over 300 organizations that are working in interdisciplinary teams. The map will be open-ended, bottom-up, interactive and three-dimensional: anyone can subscribe if they consider themselves to be part of this industry, and they will share their connections with the “network of networks” in the field. The map will be under permanent construction and “growing up in public.”

Alongside this map we are working on a white paper about the ontology of the concept of the lab and the myth of innovation, a series of field notes as tidings of the research and as reports on specific case studies and best practices. Here on Immerse, we hope to share these travels.

Coming up, stories about:

- Festivals as Labs: about angels, superpowers and flexible realities, and how themes function as tools to understand the relationship between technology and society.

- Sacred Hill: a research lab that questions human essence through virtual reality spaces.

- Trust me, I’m an Algorithm: How artists help us understand the true nature of things by being disruptive, inventive and humorous.

- The Internet is Broken: how can we save it. A case study to reclaim the public sphere online.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.