Meet the new Co-Creation Journalism Fellow

When she finally won her Freedom of Information Act requests in court, filmmaker Assia Boundaoui was granted access to tens of thousands of pages of FBI documentation from years of secret surveillance of her community.

“I had won. But I was still looking at thousands of pages of FBI documents full of black holes,” she said. “I was extraordinarily frustrated as a journalist, and felt I had hit a wall.”

Renowned Algerian-American documentarian Assia Boundaoui returns as a new Co-Creation Journalism Fellow at MIT Open Documentary Lab with her new work, Inverse Surveillance Project. She describes it as a “hybrid documentary, multimedia, AI project, co-created with my immigrant-Muslim community in Chicago, which repurposes thousands of declassified FBI records collected during decades of surveillance, as raw material for creating a counter-narrative and reimagining the secret archive. Using AI fuelled truth-seeking and traditional Arab cross-stitch embroidery we will design/produce a co-created process that makes space for a community traumatized by state surveillance to build power, seek truth, and heal.”

I spoke with Assia about the project this summer. Here’s an edited version of that conversation.

Kat Cizek (KC): What was the genesis of the Inverse Surveillance project?

Assia Boundaoui (AB): In 2013, I began making a documentary film called The Feeling of Being Watched, about the neighborhood where I grew up in Bridgeview, Illinois in Chicago — Southwest suburbs — an immigrant Arab Muslim community. For as long as I can remember, everyone in my neighborhood has always felt that we were under government surveillance. As a journalist, I wanted to investigate and find out what happened. I found an FBI investigation called Operation Vulgar Betrayal, FBI’s largest domestic terrorism investigation in the US before 9/11 and it was focused on my neighborhood.

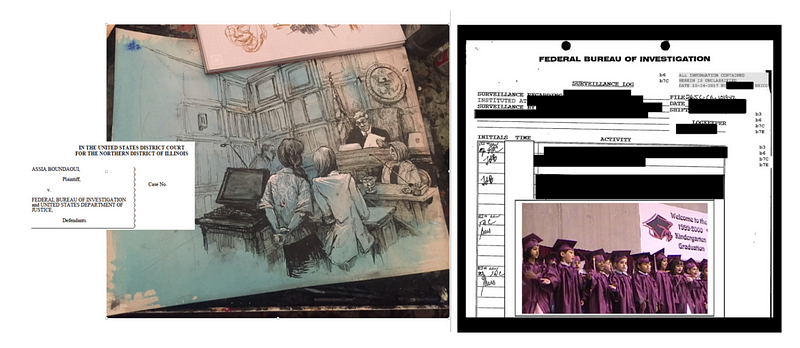

Artistic renderings of court

proceedings of Boundaoui’s FOIA requests, by Molly Crabapple.

Artistic renderings of court

proceedings of Boundaoui’s FOIA requests, by Molly Crabapple.In the course of making the film, I filed Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, compelling the government to release any records that they collected in the course of this investigation of my community. They denied having them at first. After a year, they admitted to having 30,000 pages of records and told me that it would take five to seven years to release them. In concert with a lot of people and a lot of supporters, I filed a lawsuit against the FBI, and two years into the lawsuit, the judge ordered the FBI to release all 33,000 pages to me within about a year and a half.

Every month I would get 3,500 pages of records and usually, more than two-thirds of them were redacted, so … I get something like 900 pages. And in those 900 pages, they are additionally full of black holes at places where the government had redacted, — had disappeared — information about this investigation.

In-between the holes, there was an image that we pieced together. Basically, the FBI had seen my immigrant Muslim community as a criminal network. An organized criminal network. What we actually are is a network of an immigrant community. The FBI saw things like people donating to Muslim charities, donating to their mosques, borrowing money from each other. In an immigrant community, these are things that are very ordinary. It’s part of the fibers of our community. These things that were normal for us were seen by the FBI as suspicious, as nefarious, as evidence of an organized crime network.

One of the most troubling things that came out of those documents was this redacted space. As a journalist, I was very, very frustrated that I had gone to war with the FBI for transparency to actually find out and get these records. I had won, but I was still looking at documents full of black holes. I was extraordinarily frustrated as a journalist and felt I had hit a wall.

Boundaoui’s 2018 documentary,

The Feeling of Being Watched.

Boundaoui’s 2018 documentary,

The Feeling of Being Watched.KC: So this project picks up where your film leaves off.

AB: The film leaves off with this idea that we can’t stop surveillance. We can’t stop the state from surveilling us, but we have a power and responsibility — especially those of us who have been surveilled in communities of color — to watch back, to watch the watchers. And that’s where I leave it off. That’s where the film ends. And I think the Inverse surveillance project tries to answer that dilemma. The answer is community. The answer is citizen under-sight.

We talk about transparency and impunity, we talk about rights, but we rarely talk about trauma and healing when it comes to state surveillance. How can we facilitate healing from this collective trauma that we experienced as a community?

Where’s the salve? How do we collectively heal? When you’re positioned in a place, there’s no parachuting in and out to make a film and tell a story when you’re in community. It means that when you make a film to expose a lot of pain and trauma, that there needs to be more than that.

Co-creation provides that something else. It’s not something that we do for community, or we leave behind even as a benefits agreement, it’s something that we do with community. That’s this project: to co-create with my community in Chicago, a multimedia visual art installation, an AI project that repurposes a secret archive and uses it as our canvas basically to rewrite the narrative that the FBI wrote about us for so long and to create our own community archive.

Boundaoui will co-create

story circles in the community, experimenting with different media, including audio, video,

illustration, and Tatreez, Palestinian cross-stitch embroidery. (image courtesy Tatreez &

Tea)

Boundaoui will co-create

story circles in the community, experimenting with different media, including audio, video,

illustration, and Tatreez, Palestinian cross-stitch embroidery. (image courtesy Tatreez &

Tea)KC: Tell us more about the role of AI in the project, about co-creating with the AI.

AB: Most Redactions expire after about 40 years. And what happened to my community is not at all a unique thing. There is a history in this country, centuries-long history of state surveillance of communities of color. And there are hundreds of thousands of records about those investigations that targeted the black community, civil rights movement, black power movement in the 60s, the Japanese American community in the 30s and the 20s, the Puerto Rican independence movement in the 80s. A lot of these records are fully unredacted at this point.

The idea to use artificial intelligence in the Inverse Surveillance project by coding a machine-learning algorithm to imagine what might be behind the redacted spaces in the FOIA records. This data set will be made up of two parts: it’ll be historical, and the other part will be anecdotal from the community. The historical part tries to pull together all of the records that have been released from the FBI records of the [historical] surveillance of communities of color, and take that unredacted record and use it to try to imagine what might be behind the redacted spaces in the records of my community. The second part of the data set is the idea to have people share their stories in non-traditional ways, in story circles, and different ways in the community, in ways that don’t re-traumatize people but offer a way, a path towards healing that also is a benefit to people.

These data sets will help the machine learn, and we can begin to imagine a new narrative in that redacted space.

It’s beyond simply just predicting what information is redacted. We’re co-creating with AI to create a counter-narrative, using people’s recollections, using people’s lived experiences. I call it a hybrid documentary project because the question is: where does the journalistic need for information for facts end and the emotional desire for meaning come in? When we’re looking at the redactions, it’s not to just to predict what information might have been disappeared, it’s more than that. Meaning is important too.

Boundaoui’s 2018 documentary,

The Feeling of Being Watched.

Boundaoui’s 2018 documentary,

The Feeling of Being Watched.KC: What is co-creative journalism? Where does the journalism end?

AB: I won the Livingston Award for National Reporting and the main judge, David Remnick, who is the editor-in-chief of The New Yorker, explained why they chose my film. He said, “I looked at the title and I started watching the film and I said, ’Journalists don’t care about feelings. This is not… What does feelings have to do with journalism?’ And then he went on to say, how I changed his mind when he watched the film. And I think new journalists are concerned with feelings. We are. I think that I’m concerned with meaning beyond facts also.

My use of primary sources, the use of interviews with primary sources, the freedom of information act requests, using FOIA as a tool, all of that is the practice of doing journalism. But when you’re not able to access certain information, how do you make meaning in those blank spots? Hybrid journalism practice is also a decolonial one. A lot of journalism is very, very colonized, as it talks about objectivity, it talks about having massive distance in the gaze between the one seeing and the one being watched, which is in fact, a surveillance position.

I want to close that gap. I don’t want that distance. I am positioning myself within community and inside community.

Objectivity is a colonial dog whistle. In co-creation, the gaze is from the inside, it’s not from the outside looking in. It disrupts a lot of common little things about establishment journalism that will always value government authority opinion, always over the peoples, over a person without a title.

A lot of the violence we experienced in our community came not just from the surveillance gaze of the FBI, it also came with local and national news coverage. It came with this red paint of terrorism, the ‘terrorist next door’ narrative that was constantly written about us. And we have a deep distrust of journalists in our community and of reporters. It’s really dangerous because it means that we don’t take part in the narratives about us. We don’t even like to speak and give quotes. We don’t get involved at all. We’re wary of the whole thing.

Co-creation disrupts authorship in fundamental ways that journalism can’t even define itself without. So it’s very interesting that when you bring those two things together, you’re talking about a decolonized practice of doing journalism. That’s what co-creation is in journalism.

The new Co-Creation Journalism Fellow at MIT Open Documentary Fellow is generously sponsored by Just FIlms at Ford Foundation.

As an extension of her earlier

“Stories of Surveillance” Co-Creation/Open Doc Lab fellowship, Boundaoui worked with projection

artist Robin Bell to “project redacted FBI documents onto government buildings, specifically the

the FBI Hoover building in DC and the NSA Titanpointe building in New York city. On the sides of

these buildings, we projected the redacted documents and in the black holes I projected videos

and family photos from my personal family archives of what we were up to in the 90s, juxtaposing

the really mundane everyday things we were doing. Graduations and picnics and barbecues and

camping, our family photos and our archive into the black holes of the FBI documents,

juxtaposing what they were saying about us, with what we were actually up to, and also their

archive with our archive.”

As an extension of her earlier

“Stories of Surveillance” Co-Creation/Open Doc Lab fellowship, Boundaoui worked with projection

artist Robin Bell to “project redacted FBI documents onto government buildings, specifically the

the FBI Hoover building in DC and the NSA Titanpointe building in New York city. On the sides of

these buildings, we projected the redacted documents and in the black holes I projected videos

and family photos from my personal family archives of what we were up to in the 90s, juxtaposing

the really mundane everyday things we were doing. Graduations and picnics and barbecues and

camping, our family photos and our archive into the black holes of the FBI documents,

juxtaposing what they were saying about us, with what we were actually up to, and also their

archive with our archive.”Collective Wisdom is an Immerse series created in collaboration with Co-Creation Studio at MIT Open Documentary Lab. Immerse’s series features excerpts from MIT Open Documentary Lab’s larger field study — Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media within Communities, across Disciplines and with Algorithms — as well as bonus interviews and exclusive content.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.