An interview with Sara Snyder of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery

Sarah

Snyder. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Sarah

Snyder. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art MuseumSara Snyder is the chief of External Affairs and Digital Strategies at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery. Immerse editor Jessica Clark spoke with her about how these two institutions are discovering, creating, and exhibiting 360 videos, VR, and other interactive works.

Tell us a bit about your work.

I do public-facing work with the museum, from communications marketing and social media to digital video production and various events and activities. Most of that is centered on our temporary exhibits. We have up to a dozen shows a year across two main buildings

How long have you been experimenting with immersive tech?

We started working in VR in 2016. At that time, the Renwick Gallery had just reopened after renovation. We built the museum with an immersive installation, Wonder. It was nine galleries, each with site-specific work by contemporary artists who had been commissioned to explore common materials and craft in a new way.

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1,

2015. Photo by Ron Blunt. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1,

2015. Photo by Ron Blunt. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art MuseumThat show was runaway success; we had some of the best attendance we’d ever seen at the gallery. Wonder was meant to transport visitors into thinking about everyday objects in a different way. There was an installation by Gabriel Dawe, where he filled the room with threads in rainbow hues. You felt as if you were in a magical environment but it all crafted out of simple thread.

People loved the show and asked us how we were going to capture it. It was site-specific, so it would be gone. At that time in 2016, it seemed like everybody was getting a 360 camera and so we worked hard before the show closed to capture it as best we could in high-resolution 360. We created an app, which you can still download on your phone, Wonder 360, and it’s a little time capsule of the show.

We showed it to one of our board members and he thought it was okay but wanted to be able to move freely within the space, as a fully rendered three-dimensional world. That’s the limitation of 360 video. So, he put us in touch with friends and we connected with VR producers. We also talked to Intel, our funding partner, which was interested in seeing VR used for purposes other than gaming.

We’ve since done two VR projects with Intel support. One of them is called Beyond the Walls, which is a capture of our permanent collection galleries and our main building. It takes some works from the late nineteenth century and some from the twentieth century and lets you explore those works in our museum. There are also magical portals hidden around the space that allow users to teleport. For example, you’re standing in front of the painting of the Aurora Borealis, thinking about how Edwin Church saw this national phenomenon at the end of the Civil War — and what it meant to him — and then you can be transported to see footage of Aurora Borealis in the sky, taken in Iceland.

There’s also a sculpture that was created as a graveside memorial at Rock Creek Cemetery in DC, and another one in the art museum. So, we created a teleportation tunnel that allows people to stand in front of the version at the museum and be “transported” to the cemetery with the breeze in the background. Some of the greatest American sculpture in this country is in cemeteries, so it’s an educational exploration. It took a while to get the interpretation part right. We hope to have that for download within a few weeks.

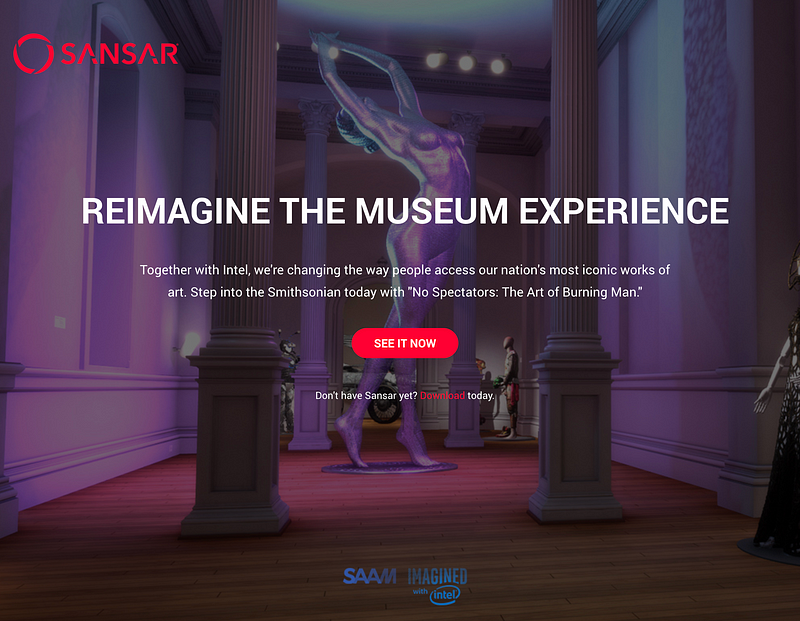

The other project we worked on with Intel is perhaps the most ambitious, No Spectators: the Art of Burning Man. We knew we wanted to capture it in 3D and make sure it could be rendered in a fully explorable world. So we captured the whole show, put it on Sansar. The idea here is that you can see a museum show with others — your friends’ avatars can be walking around experiencing the VR together. The download is free but the room-scale experience can really only be experienced with the fancy headsets, such as Vibe or Oculus.

An important part of Burning Man is the environment in which is takes place, at the open desert in Nevada, so this doesn’t really capture the feeling of what Burning Man is like in person. But we were able to take a number of outdoor sculptures that were commissioned for the neighborhood and virtually place them in an imaginary desert-scape. You can walk out the door and instead of being in the Golden Triangle neighborhood of northwest D.C., you’re in a desert-scape with 40 people and you can see this sculpture in that context. You can climb up on top of the sculpture, something we definitely don’t let you do in the museum!

We sent that show on the road. It’s in Cincinnati now. It’ll be in Oakland later, but the virtual capture of that show can live on and reach more people than are able to come in person.

What kind of responses are you getting from the exhibition?

The goal with the room-scale, more ambitious projects was to see whether there was any interest. This was all very untested; there was no benchmark for what success would look like. The responses we received from visitors have been wonderful. Many people have come away raving. I feel like offering art to people in this platform is important. Gaming and entertainment are a given, but it has the potential of offering completely transformative transporting experiences.

Are you at a point where you can find those artists?

Yes, we worked at one of them with the Burning Man show: Android Jones. He created a fictional landscapes inspired by Burning Man. We’re seeing more artists. Companies such as HTC and others are investing in VR; it’s a long-term strategy to have larger audience for their platforms.

What other projects are on the docket?

One other thing that our museum does is engage with the gaming. We had a really popular show in 2012, The Art of Video Games. I expect to see more exploration around media arts. If you can build sculpture and create immersive environments on another planet in VR, why not?

But it’s a lot of hardware maintenance and staffing. When we had the Android Jones VR work in the gallery, we had two gallery attendants who worked full-time to help people get in and out of the headsets. There’s a lot of needed wiping and disinfecting and charging the hand controllers. I’m much more interested in how we can provide and curate content for people who have the technology available to them in other spaces — homes or classrooms, for instance — than in doing that.

We’re just not quite there yet with the adoption, but we’re seeing incredible progress with the untethered headset. Most people don’t want to set up a whole room in their house for VR. It needs to be more flexible. To me, the holy grail is when the tech disappears, and you’re in the world.

This must be hard to find. Where do you go to talk about emerging media in the museum space?

Museum Computer Network and Museums and the Web are two annual meetings that are really inspirational. Also, SXSW.

In a follow-up, Snyder noted that she’d be remiss if she didn’t also mention the current show at the Renwick Gallery, Ginny Ruffner: Reforestation of the Imagination, which mixes AR with physical artworks. Plus, the annual SAAM Arcade earlier this week focused on “breaking barriers… showcasing projects that recognize and relish the diversity of gaming audiences, allowing a wide array of players to see themselves and their interests reflected on screen.”

This piece is part of an issue of Immerse sponsored by the Knight Foundation in conjunction with Knight’s call for ideas to advance immersive arts experiences. Open for applications through August 12, the call offers recipients a share of $750,000 in funding, as well as optional technical support from Microsoft. Learn more.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.