Each issue, Immerse editor Jessica Clark explores the implications of storytelling and art at the cusp of the physical and the digital.

“At this point, VR and AR are two of the last major technologies that haven’t faced a huge scandal involving genocide, mass surveillance, election tampering, or the wholesale dissolution of truth,” wrote Andi Robertson for The Verge at the cusp of the new year.

Given the breakneck pace of development for new forms of digitally mediated reality, the question is: How soon?

Not soon enough, if you’re Kevin Kelly, who bills himself as “Senior Maverick” for Wired. In his claustrophobic March cover story, he welcomes us all to “Mirrorworld” — a future place he claims is on the way, which will consist of a full-sized digital twin of every place and thing on earth, queued up as a “grand third platform” to follow the web and social media. Whoever dominates it, he writes, “will become among the wealthiest and most powerful people and companies in history.”

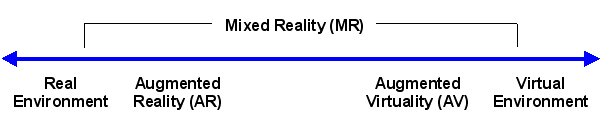

From Wikipedia: The

Reality-virtuality continuum

From Wikipedia: The

Reality-virtuality continuumTo keep things short, let’s use the term “mixed reality” (MR) to include augmented and extended reality platforms and content, plus the AI and location services often used in conjunction with such experiences. Contemporary MR offers rudimentary versions of this grand vision, suggests Kelly. In typical fashion, he notes that digitizing everything everywhere will produce some unforeseen problems, and probably kill a few people in the process, but in the end it’ll all be worth it.

“We know there will be severe physiological and psychological effects of dwelling in dual worlds,” Kelly shrugs. “The great paradox is that the only way to understand how AR works is to build AR and test ourselves in it.” He also allows that to “synchronize the virtual twins of all places and all things with the real places and things while rendering it visible to millions — will require tracking people and things to a degree that can only be called a total surveillance state.”

But, hey, in return we’ll get what Kelly calls a new “super power” — i.e. “super vision,” which will allow us to see not just the familiar tangible world, but the “virtual ghosts” of objects, and perhaps even the avatars of the AIs whose voices we can only hear right now. “Inside the mirrorworld, agents like Siri and Alexa will take on 3D forms that can see and be seen,” he predicts. “Their eyes will be the embedded billion eyes of the matrix.” (Paging Jordan Peele…)

While Kelly waxes ecstatic about “super vision,” he’s less bullish on, well, supervision. He asserts that neither any government nor a “Big Brother” monopolistic corporation should mar the future he projects. Instead, some vague and unimagined authority will help to produce the “mechanisms in the mirror world to prevent fakes, stop illicit deletions, spot rogue insertions, remove spam, and reject insecure parts.” Maybe blockchain can solve this, he hand waves. Well, who cares, really. As long as someone gets rich!

None of this hubris is really surprising — after all, Kelly co-founded Wired and writes books with titles such as The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future. Sweeping over-generalizations and grating techno-utopianism even in the face of a lethal tsunami of backlash are his bread-and-butter.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, scholars, artists, media-makers and advocates are treading water, still trying to figure out how to counter the excesses of previous media forms while preparing for this next deluge. Out front: journalists, documentary filmmakers, designers and civic tech developers, busy trying to hold the line on verifiable facts, find ways to generate empathy among compassion-fatigued and choice-addled audience members, and create trustworthy mechanisms for engaging people in the democratic process.

Already we’re dealing with the fallout from previous failures in media regulation and civic education: a president spawned by reality TV and tabloids who denigrates the press, and a digital public sphere distorted by bots, hackers and trolls. Attempts to provide media literacy training to help citizens decipher twenty-first century forms of information assume incorrectly that they’ve already mastered basic twentieth-century skills of literacy and numeracy. Now, how will yet another layer of reality — virtual, mixed, augmented or whatever — further tangle everyone’s perceptions?

Here at Immerse, we tend to take an optimistic view of new technologies, seeing them as opportunities for creativity, self-expression, organizing, and connection. But — real talk — both U.S. and global media activists need some rapid-response methods for forging standards, practices, and policy remedies posthaste. While we’re still busy trying to save journalism and regulate Facebook, MR devices and apps are creeping into people’s everyday habits, changing the ways they conceptualize the world around them, form their own identities, interpret evidence, and create social bonds. The advent of 5G connectivity is going to turbocharge these technologies.

A recent conference I attended at Penn celebrating the launch of the Media, Inequality and Change (MIC) center reveals the contours of the social and policy issues raised by any new set of media and communications tools. There are issues of localism vs. consolidation; the status and treatment of media workers; concerns about obscenity, libel, and outright lying; balancing of market freedom against the public interest. There are the carrots — how do we create incentives, networks, infrastructure, and funding to support public-interest news, storytelling, educational content, and community organizing — and the sticks to punish and wrest concessions from the companies, moguls, and bad actors who are polluting our public sphere.

There’s no need to reinvent the wheel here — the very same companies currently under the microscope for violating users’ privacy and shredding journalistic marketplaces via their social platforms and digital services are the ones dominating the emerging MR marketplace. Pick your target: the “FAANG” corporations (Facebook/Apple/Amazon/Netflix/Google) or the “Big Nine” that futurist Amy Webb writes about in her latest book (subtract Netflix and add Alibaba, Baidu, Microsoft, Tencent, and IBM.) These powerful global companies are busy building proprietary platforms, gadgets, services, and experiences that will underpin the MR content creation and distribution for years to come. We need to pay attention to this now rather than waiting for new huge scandals to force us into reaction.

Still from

a new immersive POV Spark project, “Changing Same: An American Pilgrimage”

Still from

a new immersive POV Spark project, “Changing Same: An American Pilgrimage”When it comes to funding better alternatives, in the U.S., some of this work in the immersive media arena is already taking place within established public broadcasting and public access organizations — which were funded via previous policy interventions. Take, for example, the recent announcement that POV just launched Spark, a new unit that produces interactive/immersive experiences. The Brookline Interactive Group — a media arts center “rooted in the tradition of public access television” — has pivoted to training community members how to make VR/XR, and, unlike many less inventive peer organizations, is healthy and growing. Black Public Media has also gone all in on VR and other new technologies, launching a 360 Incubator and hosting a BPM+ screening series to highlight black creatives producing in this space.

For the most part, though, it has proven difficult to force legacy public media organizations to invent or invest in new ways of making media. One bright note: a recent summit organized by Matt Locke of Storythings aimed to reconceive a “public media stack,” which would provide “a sustainable ecosystem of ethical, independent technologies without exploiting the data, content, or relationships that are critical [to such projects].” There, developers, producers and wonks gamely rolled up their sleeves to map out 130+ software products currently being used to create, distribute, collaborate around, or evaluate digital media—and to speed-write a new definition for the new forms of “public media” these tools enable.

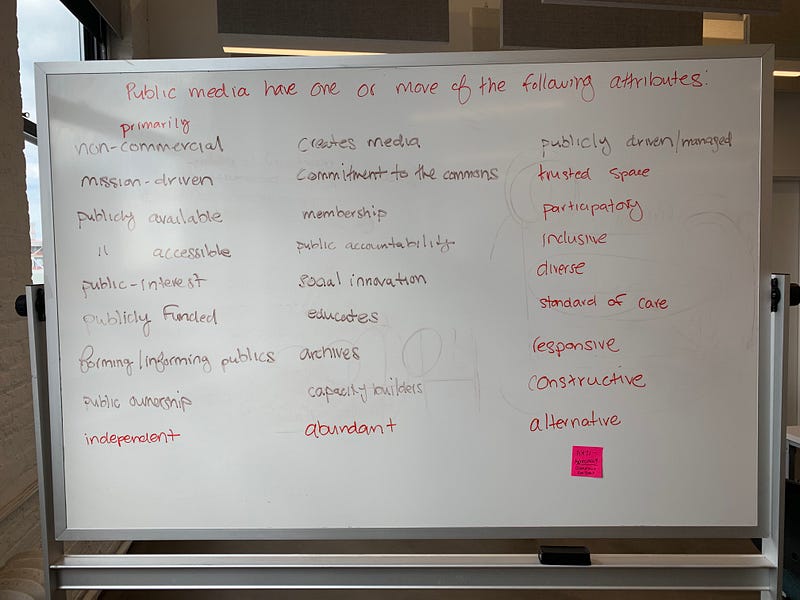

Brainstorming at the Public Media Stack Summit

(Photo by Jessica Clark)

Brainstorming at the Public Media Stack Summit

(Photo by Jessica Clark)But other countries are already much further ahead both in terms of laying down rules for digital platforms (for better or worse) and investing in emerging content. The National Film Board of Canada has long been a leading funder and incubator of incredible media experiments, for example, and the UK is funding R&D in virtual, augmented, and mixed reality technologies. Finland is going gangbusters on digital literacy training. At the MIC center event, I picked up Media Manifesto 2019: A Media Policy Fit for the 21st Century—a progressive vision for even more sweeping and future-facing reforms in the UK.

In short, the U.S. is lagging in media policy and public funding for MR and adjacent media experiments. This puts us at both a moral and a competitive disadvantage. As Kelly suggests, there’s no getting out of the fact that we are all going to have to reckon with the consequences of mixing reality in new and disruptive ways. So what can we do together to rapidly devise a better way through?

Photo (banner): Michio Morimoto

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.