On the guerrilla potential of AR, dramatic arcs, and the politics of visibility

In 2010, a group of “uninvited” artists took over MoMA by placing their artwork in its galleries using location-based augmented reality (AR). The pieces were only visible to those who knew they existed and used the accompanying mobile application. “We AR in MoMA” was a groundbreaking AR intervention in which the organizers, Mark Skwarek and Sander Veenhof, questioned: what is the impact of AR on our public and private spaces? Is the distinction between public and private spaces fading, or is reality fragmenting into individual perceptions?

A year later, Tamiko Thiel, one of the artists who exhibited at “We AR in MoMa,” co-founded an artists group with Skwarek and Veenhof and led their intervention at the Venice Biennale. Known as Manifest.AR, they were not only early practitioners of AR but wrote the augmented art manifesto. The group opened the conversation for the value of AR as a form of art.

“ARt Critic

Face Matrix,” augmented reality installation, Tamiko Thiel, 2010. Screenshots from the AR

intervention “We AR in MoMA,” MoMA New York.

“ARt Critic

Face Matrix,” augmented reality installation, Tamiko Thiel, 2010. Screenshots from the AR

intervention “We AR in MoMA,” MoMA New York.A pioneer in both Virtual Reality (VR) and AR, Thiel is an internationally recognized digital media artist who explores the interplay of place, space, the body, and cultural identity in works that take the form of an AI supercomputer, sculpture, digital prints, videos, interactive 3D virtual worlds, AR, and deepfake AI installations in situ in galleries, museums, and public space. In 1994, Thiel worked with Steven Spielberg on the pioneering Starbright World, an online virtual world playspace, commissioned by the Starbright Foundation, in which seriously ill children in hospitals all over the U.S. met via a network to play together as avatars in the virtual 3D world and discuss their concerns via text chat, audio, or video conferencing. Thus, Thiel’s trajectory has been characterized by her ability to recognize the value of new approaches to art and storytelling, and to chart blueprints for their implementation in the field.

My research at the Open Documentary Lab (ODL) on augmenting public spaces has been part of a two year initiative to explore augmented technologies and techniques used by communities to claim, reclaim, and reimagine their public spaces. For instance, AR adds to, through a phone’s camera, the user’s real-life experience, whereas VR produces an alternate world in which the player uses special equipment such as computers, sensors, headsets, and gloves. I admire how Thiel deploys AR as a way to question institutionalized practices of accessibility. AR does not require permission or invitation, nor gatekeepers or curators who define whether the art is worthy enough to occupy private or public space. Moreover, unlike a physical artwork that is removed after its exhibition, AR artwork remains on site as long as the artist wishes; neither institutions nor the government is able to remove it. For Thiel, the idea that they could place their art wherever they wanted was liberating.

After her participation in the ODL panel “LAYERS OF PLACE: The Art of Augmenting Public Spaces and Places with Stories and Technologies,” I spoke with Thiel about her work in AR and VR. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

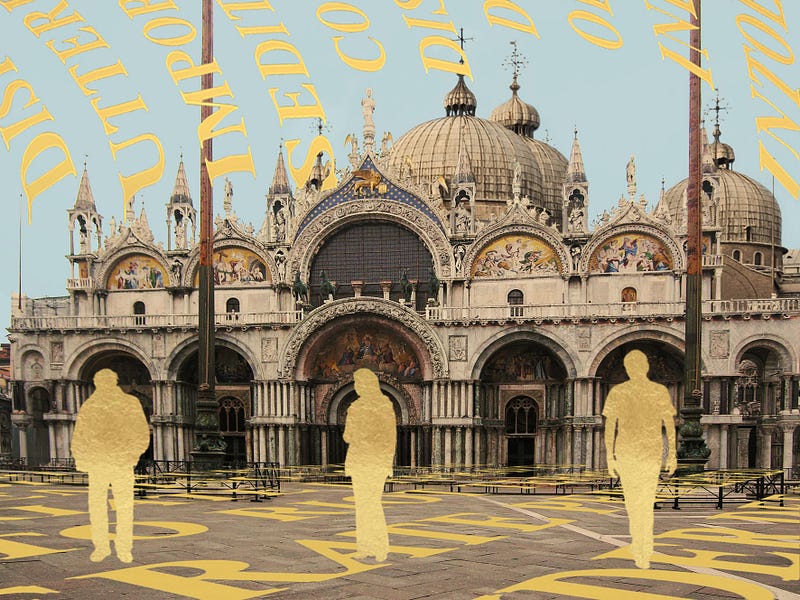

“Shades of

Absence: Public Voids” augmented reality intervention into the Venice Biennial, Tamiko Thiel,

2011.

“Shades of

Absence: Public Voids” augmented reality intervention into the Venice Biennial, Tamiko Thiel,

2011.Immerse: In a digital world, why do you think physical space still matters?

Tamiko Thiel: Even the virtual reality installations that I’ve done always include moving a body through space. In augmented reality, you have to physically move your body through space to see the entire installation. For me, the appropriate receptive and kinesthetic senses of the body are a very important part of perceiving and interacting with virtual and augmented space.

Immerse: What’s unique about AR compared to VR?

TT: I spent 15 years working on a total of three virtual reality projects. Working in VR means that you spend a lot of time researching the site and reconstructing it, and only then, you can start playing around. With AR, I could use an existing site and I didn’t have to spend four years recreating a site before I could start playing with it as in my VR artwork. I think the fastest turnaround that I’ve ever had was maybe two hours or even less. I was in Lisbon and I was staying a couple of blocks away from the square where the Portuguese Carnation Revolution had started. I found a carnation on the internet and created a rain of carnations. I installed the piece with GPS at that Square, and it turned out really well. And I thought: I can, within a couple of hours, create an artwork that speaks to a deeper history of this very specific site. It was incredibly empowering.

Immerse: Do you apply your theory of dramatic structure, an experiential viewpoint, to your AR work? Is there any AR project that illustrates the use of sequence to create a dramatic structure?

TT: With AR, I don’t want to focus on people who have the newest, most expensive smartphones; I want to make it more inclusive. Therefore, I’ve always tried to keep my works simple enough so that they can be seen by a large number of people, and that has meant keeping the content a little bit reduced. With virtual reality, you’re working with so much more computing power, so you can afford to create these more complicated dramatic structures, but as the old smartphones become more powerful I hope to do more and more of that with augmented reality as well.

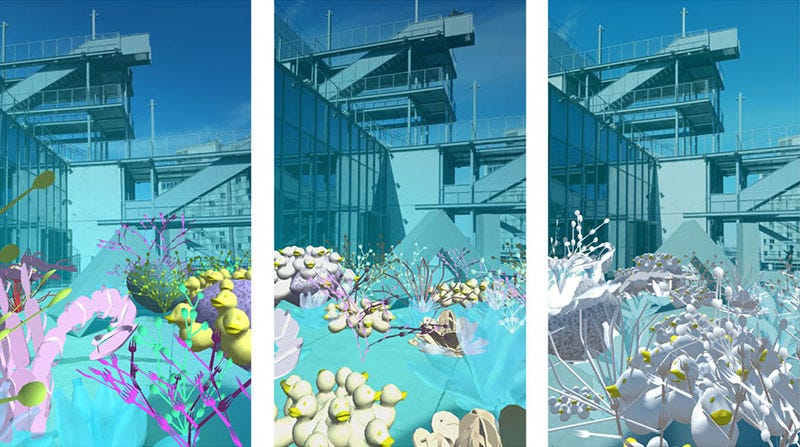

In a piece I’m working on right now together with my co-artist /p, ReWildAR, for the FUTURES exhibit at the Smithsonian, I’m creating a wildflower and pollinator insect meadow, and there, I will be setting up a sort of a dramatic arc that takes you from early spring to late summer and back again. You have some flowers that come out in the early spring and then fade away, so there’s sort of a melody of both flowers and their associated pollinators fading in and out. This is the first time that I’ve thought, okay, even with low-powered smartphones I should be able to create a certain dramatic arc. It’s a little bit of an experiment.

“ReWildAR” AR installation, Tamiko Thiel and /p, 2021. Commissioned by the

Smithsonian Institution for the Arts and Industry Building

“ReWildAR” AR installation, Tamiko Thiel and /p, 2021. Commissioned by the

Smithsonian Institution for the Arts and Industry BuildingImmerse: In your VR projects, users play a central role in constructing their own narrative. How do you conceptualize the role of users in your AR projects? What do you think about the user’s agency and accountability, for instance, in Biomer Skelters?

TT: When you’re playing a game you usually have to try as hard as possible, you have to put out as much energy as possible in order to win. In the area of biofeedback, there’s a different mindset. Biomer Skelters was done together with Will Pappenheimer, one of my colleagues from Manifest.AR. We spent a lot of time talking with scientists working with biosensors at the Liverpool John Moores University. They also talked about ideas like “relaxed to win.” The concept of relaxing to win sounded interesting to me, and Will and I came up with the idea of competitively coating the entire city with vegetation. Will suggested participants had to choose a “team”: You can be either an Indigenator, who is planting indigenous plants, or an Exoticator planting invasive species. It’s an interesting use of terms because we often talk about invasive plants taking over from the native plants. If you use the same words to talk about humans, however, you get into very difficult realms of racism, colonialism, imperialism and alterity. I wanted to bring that into the discussion. We were hoping that somebody would pick it up, but the venues said, “no, let’s just talk about plants,” which was too bad.

Immerse: Something that I have been puzzled about is the invisibility of AR. If you have invisible art, you might want to heighten its awareness. I’m also intrigued by the recursiveness of AR. For instance, for your piece Unexpected Growth, there was a projector that was displaying what the people were seeing. What are your thoughts about the visibility of AR?

TT: One of the things that got me interested in AR as a geolocated form is that it doesn’t need a physical object, and, therefore you can do it anywhere you want. The very first time that I worked with augmented reality was this intervention into the MoMA organized by Mark Skwarek and Sander Veehof, and the whole point was that we were not allowed to put our artwork inside; we couldn’t put physical images nor objects into MoMA. That’s part of how an institution like MoMA defines the canon of what they allow inside their doors. With AR, it was the realization that walls are not an impediment anymore. We can put our artwork anywhere, so it was that specific ability that they can be used for guerrilla interventions where, otherwise, we would need to spend a lot of time and energy trying to get permission from whatever authority controls that space. Or the whole point might be that you know that authority would not authorize you to put the artwork there and therefore you are using AR to locate it there, to get around exactly that prohibition.

“Unexpected

Growth,” augmented reality installation, Tamiko Thiel and /p, 2018. Commissioned by the Whitney

Museum of American Art, and now in the collection.

“Unexpected

Growth,” augmented reality installation, Tamiko Thiel and /p, 2018. Commissioned by the Whitney

Museum of American Art, and now in the collection.Immerse: The color gold seems to reoccur in your projects. Why is that?

TT: There’s a specific technical reason. If you try making AR on a lot of different backgrounds, you’ll find that generic backgrounds are white, very dark, or various colors, but usually not gold. And, of course, gold has an association with high value and artwork in some sense. So, it’s partially because it’s wonderfully visible, no matter the background, and the other part of it is because the gold leaf is a statement in itself to say that this is a work of value.

Immerse: What’s next for you and your artwork? Are you going to continue working on AR, or are you looking towards other technologies?

TT: I’ve got several things happening. I am hoping to have a broader art practice in the future. Because as much as I love AR and VR, I also love the physical world, I love objects, I love images, and I want to be able to produce in a wide range of media.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.