There’s little doubt that the best way to pick up and learn a new language is through immersion. Removed from the creature comforts of a native tongue and surrounded by unfamiliar words, phonemes, and syntax, the brain rewires.

In Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, art and media historian Oliver Grau describes the experience of immersive media as “mentally absorbing and a process, a change, a passage from one mental state to another.” As with language immersion — which often means being embedded in a place and culture that is different from one’s own — such experiences have the potential to transport a person from their day-to-day to a wholly new mental place, transforming the way they understand the world.

In the Knight Foundation’s On View podcast episode “The Newcomers,” Vince Kadlubek, CEO and co-founder of Meow Wolf, posits that his Sante Fe-based arts organization’s wildly popular immersive storytelling exhibitions reflect a societal step beyond the experience economy to the transformation economy. No longer are consumers willing to settle for any old experience; now, people want to “pay for a transformational experience,” one that leaves them changed in some way. On View host Chris Barr follows up: “For an experience to be transformational, it has to provide meaning.”

Seen in the context of capitalism, the idea of consuming transformation concerns me. Can meaningful change be purchased? Can individuals repeatedly expect transformation with every transaction, at the snap of a finger or the opening of a wallet?

As a museum technologist, I’m committed to harnessing emerging technologies to deepen a visitor’s relationship with the objects and stories on view. I’ll always remember a moment at my former place of work, the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, that demonstrated the power of immersive technology. Between 1964 and 1966 Warhol created almost 500 screen tests in his Silver Factory studio using his trusty Bolex camera. He would then project them in the studio but at a slower rate, resulting in ethereal silent films — intense close-up character studies of individuals both famous and unknown.

At the museum, we created the Screen Test Machine, an interactive experience that allows visitors to be the subject of a Warhol short film. In an architectural space that harkens back to the aluminum foil-covered brick walls of Warhol’s studio, visitors sit in front of a Bolex camera that we gutted and replaced with a digital camera. After filming, the Screen Test Machine slows down the black-and-white video and sends it to their email inbox.

Screen Test

Machine at the Andy Warhol Museum

Screen Test

Machine at the Andy Warhol MuseumI once watched a woman sit for a screen test, her gaze rapt in a staring contest with the camera’s lens. The minute the whirring of the camera subsided and recording stopped, her shoulders slumped, her face transforming from one of concentration to relief. She said to her friend: “I felt like I was there, an aspiring starlet in Warhol’s studio.”

I see museums as essential to retaining real, meaningful transformation through immersion. Through their mission-based work and often-non-profit status, cultural institutions sidestep some — although admittedly, not all — of the profit-driven impulse of the transformation economy. For artists and museum professionals, the zenith of their work is to provide meaning that leaves a person changed in some way. At the same time, they recognize that transformation is gradual, a result of visitors bridging their lived experiences with outside knowledge to synthesize into new meaning.

Even though Kadlubek describes the transformation economy as society’s next evolution, museums have long been sites of immersion and transformation. Museums are perfect sites of transformation precisely because curators and artists can present objects and stories that catalyze new thinking, offer interpretation and layers of knowledge to help contextualize those objects and stories, and provide a space for reflection and discussion.

In Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums, and the Immersive View, Alison Griffiths traces the historical forebears of museological immersion. The medieval cathedral uses the monumentality of its architecture to evoke the religious sublime. She contends that the “revered gaze” developed within the walls of the cathedral — “a way of encountering and making sense of images…that are intended to be spectacular in form and content.” Cultural institutions today continue to employ such techniques, whether in the gallery or on the IMAX screen.

In the nineteenth century, artists developed panoramic paintings: large-scale, 360-degree images depicting historical scenes, military feats, or awe-inspiring landscapes, fully surrounding the audience. Artists painted traveling panoramas on transportable canvas scrolls, allowing the makers to tour their images at venues such as theaters and ballrooms for a seated audience to enjoy, often accompanied by narration and piano music.

Even the earliest museums integrated immersive elements to bring their objects and stories to life. In Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, Lawrence W. Levine points to one of the United States’ first museums as an example.

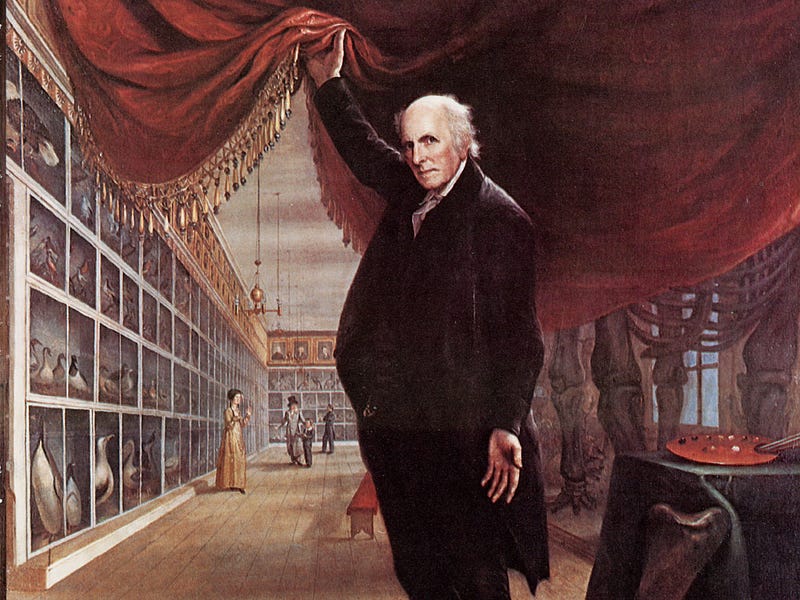

A portrait

of Charles Willson Peale in his museum

A portrait

of Charles Willson Peale in his museumCharles Willson Peale founded his museum in Philadelphia in 1786 to house the botanical, animalian, and archaeological specimens he collected during scientific expeditions. Peale was committed to elevating the scientific standards in his institution: he adopted the biological Linnaean taxonomy to classify objects within his collection, in contrast to counterparts who often presented their collections as oddities of the natural world. Still, Levine argues, he hoped to “make his museum a source of enlightenment and ‘rational amusement.’ ” He developed the progenitor of today’s natural history museum staple — the diorama — by painting landscape backdrops for his taxidermy specimens. By inserting the stuffed creatures into lifelike scenes, Peale simultaneously delighted audiences while connecting the object to its original context.

If immersion has been an integral part of museums throughout their history, so have the anxieties that such immersion is taking away from institution’s educational missions and pandering to the whims of the masses. According to Levine, museums in the early nineteenth century were a part of the larger culture that fluidly blended education with entertainment. But this would quickly change around the middle of the century. Griffiths points to moral panics among museum staffers that are not so dissimilar to what you might hear at a cultural institution today.

At the 1906 British Museums Association conference, one critic argued that the dioramic tendency in natural history museums had gone too far, to the point of severing museum-goers from the natural world:

Slabs of nature were transported bodily into museum cases and their lessons rendered so obvious that people found it easier to stroll into a museum to learn the habits of animals than to lie in wait for them in their native fields…Thus, instead of creating naturalists, our museum helped people to lose the naturalist’s chief faculty — observation.

Often, the moral panics took on a classist dimension. The official guide of the 1874 International Exhibition reminded readers that “the main object of this series of Exhibitions is not the bringing together of great masses of works, and the attraction of great holiday-making crowds but the instruction of the public in art, science, and manufacture.” As Griffiths notes, the fear of “holiday people” — code for working class — disrupted the association of cultural institutions as something for an educated gentry.

MIT’s Open Documentary Lab Moments of Innovation Timeline highlights a panoply of other media that serve as precursors to today’s immersive storytelling technologies. From stereoscope images to planetarium documentaries, we’ve long used emerging technologies of the time to transport us to places unknown, faraway, and awe-inspiring.

As augmented, virtual, and mixed reality mature, museums have new ways to engage audiences through immersion. Instead of falling into the age-old debate of whether these technologies are better suited to educate or entertain (in itself, a false dichotomy), I hope to move beyond these conversations. Instead, I’m more interested in exploring what makes for a transformative immersive experience in today’s cultural and political climate.

The New Dimensions in Testimony project, a joint initiative of the USC Shoah Foundation and the USC Institute for Creative Technologies, uses artificial intelligence and 3D capture to bring recordings of interviews with Holocaust survivors to life. Visitors to Holocaust museums such as the ones in Washington, D.C., and Houston can now pose questions to the interviewees and receive answers in real time.

An image from New Dimensions in

Testimony, courtesy of the USC Institute for Creative Techologies.

An image from New Dimensions in

Testimony, courtesy of the USC Institute for Creative Techologies.With the rise of white supremacy in the United States and an increase in hate crimes and mass murders targeting Jewish people, it becomes all the more essential to preserve these stories. It’s invigorating to see cutting-edge technologies used in the service of advancing, as the project’s website puts it, “the age-old tradition of passing down lessons through oral storytelling.”

While New Dimensions in Testimony relies on emerging technology to create a sense of immersion, the National Museum of African American History and Culture reverts to tried-and-true techniques. From the museum’s Middle Passage gallery — devoted to the transatlantic slave trade of the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries — visitors can take a sharp right turn into a dimly lit and secluded gallery.

There, I stepped gingerly onto a narrow wooden pathway, surrounded by weathered walls evocative of a slave ship. A spotlight illuminated two powerful objects from the Portuguese slave ship São Jose: an iron ballast — used to weigh down the boat and its human cargo — and a wooden pulley block. The ship departed from Mozambique in 1794, a few weeks into the journey towards Brazil before a crash into submerged rocks sunk the ship. It’s the first and only shipwrecked slave ship ever discovered.

Divorced of their context, the iron ballast and wooden pulley block appear unremarkable. But through the use of architecture, lighting, and the juxtaposition of a few choice quotations, NMAAHC was able to bring the original meaning back to these objects. Confronting these objects, I was shaken out of my own context and immersed in the eighteenth century. I was struck by the atrocity of centuries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and enslavement in the Americas that continue to impact our society today.

To be clear, I was transformed because of the weight of history that these objects represented. But immersion was the vehicle that allowed me to be so.

This piece is part of an issue of Immerse sponsored by the Knight Foundation in conjunction with Knight’s call for ideas to advance immersive arts experiences. Open for applications through August 12, the call offers recipients a share of $750,000 in funding, as well as optional technical support from Microsoft. Learn more.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.