An artist reflects on audio‘s entanglement with environments

It’s autumn 2017. I’m in the first stages of building my new project, Only Expansion. I’m standing high up on a rooftop in Bergen at night. I can just make out the shape of the mountains. Below me the lights of boats and buildings mark out the edges of the black surface of the harbour water. I’m wearing a pair of headphones with binaural microphones attached on the outside. They feed in and out of a small embedded computing device. I can hear cars on the streets below and the faint cries of revellers. I begin playing a recording of desert wind through the device. The pre-recorded and the live are mixed together in my ears. Even though I know what it looked like, I do not picture the edge of the Sahara where it was recorded. Instead, it just seems to become weather around me, and I can only see the harbour below. But slowly the wind from the sea picks up and I begin to feel both winds against my face.

Douz,

Tunisia. Field recording site for Only Expansion

Douz,

Tunisia. Field recording site for Only Expansioncocoons

Immersion is a slippery word, one that might in one instance conjure images of being underwater and in another reading a book. It might mean being immersed in a task or immersed in the invisible microwaves of digital networks.

Yet when we talk about immersive media it often feels there is a lean towards describing a kind of cocooning. Whether that’s a darkened room filled with sound or the forward-looking and body-forgetting embrace of a VR headset, it’s often a totality — immersive media meaning something where the media itself is all-encompassing in some way, where the only “thing” you are immersed in is the work.

Its creators sometimes act as if that is all there is, as if they have erased everything else. But what if we expand our idea of immersive media beyond being only an instigator or creator of immersion, but as an exposer, a revealer?

Immersive media as something that allows us to become of aware what we are already immersed in . . .

Immersive media as a way of exposing how we exist deep inside the complex tangled ecologies of climate collapse rather than external viewers . . .

Immersive media as something that provides no vantage point . . .

Writing in The Guardian, author Robert McFarlane suggests that the overwhelming scale of climate breakdown means that “old forms of representation are experiencing drastic new pressures and being tasked with daunting new responsibilities.” We are constantly bombarded with images of raging forest fires and awesome chunks of ice falling into the sea. They might indeed offer us some kind of encounter with the eco-sublime, but is there not a risk they reinforce the distance? Where we become able to sit back into a curiously static subject/object divide:

It’s happening, but not here, and not to me.

The immersive VR experience of walking through a rainforest might move the viewer towards a sense of being in touch with different environments, but I think there’s a possibility it is just another form of distancing… of letting you look at and listen to something that you know you can turn off at any point simply by lifting the headset. It shows us the world, but does it really show us as part of it or just another passive observer?

In trying to unpack the contradictions of ecological writing, Timothy Morton suggests in his 2007 work ‘Ecology Without Nature’ that “If we could not merely figure out but actually experience the fact that we were embedded in our world, then we would be less likely to destroy it.” Sometimes simply rethinking and shifting where the edges of an immersive work are can offer something of this sense of being embedded.

The VR installation The Industry by Mirka Duijn is a documentary about illegal drug trading in the Netherlands. It combines maps and 3D renderings of buildings to offer a non-linear collection of stories that you are free to navigate through in any order you like.

Author experiencing ‘The Industry’

at Doclab in Amsterdam 2018

Author experiencing ‘The Industry’

at Doclab in Amsterdam 2018While the content was visually stunning and the situations described were intriguing, what really made an impact on me was that I experienced the piece in Amsterdam at Doclab. When I removed the headset and moved from the exhibition hall to the city streets I could feel myself still within the piece. Walking the Dutch streets, I was suddenly aware that around me the invisible networks of illicit trading, of secret rooms and suburban kingpins continued. The transition from the virtual documentary space into the tactile world felt like a singular continuous thread.

While this connection between the exhibition site and the content of the work did not seem to have been intentional on the part of the creator (it was not referenced in the work or the copy) I think it offers an insight into how shifting the edges of an immersive experience might open it up to so much more. Opening up work to unpredictable everyday environments can get messy because reality is messy and tangled. If immersive media is going to place audiences in the middle of these entanglements, rather than just showing them, it might need to be prepared for a complicated dialogue.

In my work I’ve been attempting to give audiences an experience of this entanglement through the use of augmented audio. My most recent audio walk Only Expansion takes audiences on a cinematic journey through a city, using custom electronics to remix the sound of their surroundings in real-time. It is an attempt to both simulate and evoke future climate collapse.

For the last two decades I have been making a variety of forms of audio walk, sometimes location-sensitive, sometimes just linear audio. In 2007 I had experimented with realtime audio processing, sending audiences out with laptops hidden in backpacks. Inspired by the works such as Aito Maebayashi’s Sonic Interface (1999) and Noah Vawter’s Ambient Addition (2005), I explored how augmented audio might allow people to attend to their surroundings in different ways. Somehow I never found the right conceptual rigour to continue using that form of technology until my work started responding to contemporary eco-critical debate.

I have always tried to create work that leaves space for the world to happen. Staying conscious that if I am placing audiences out in the unpredictable world, what I create should act primarily as a frame — using it as a way of highlighting and commenting on the world rather than just overlaying it. When my thematic started leaning towards climate breakdown I became conscious that while my audiences were indeed attending to their surroundings more acutely, the headphone-based systems were not inviting sound into the dialogue.

Professor Salome Voegelin from the London College of Communication suggests that in our everyday listening we are never just receivers of a soundscape; we are also always contributing to it. Every footstep, clothes rustle, and breath becomes part of our experience. There is no true division between the sound from us and the sound from there — it is all just sound.

These blurred edges and meshing together seemed to speak directly to the breaking down of the subject-object, human-nature divides.

Only Expansion was created as a way to use augmented audio not just to articulate these ideas, but to let audiences actually experience them.

without beginning or end, there is only expansion

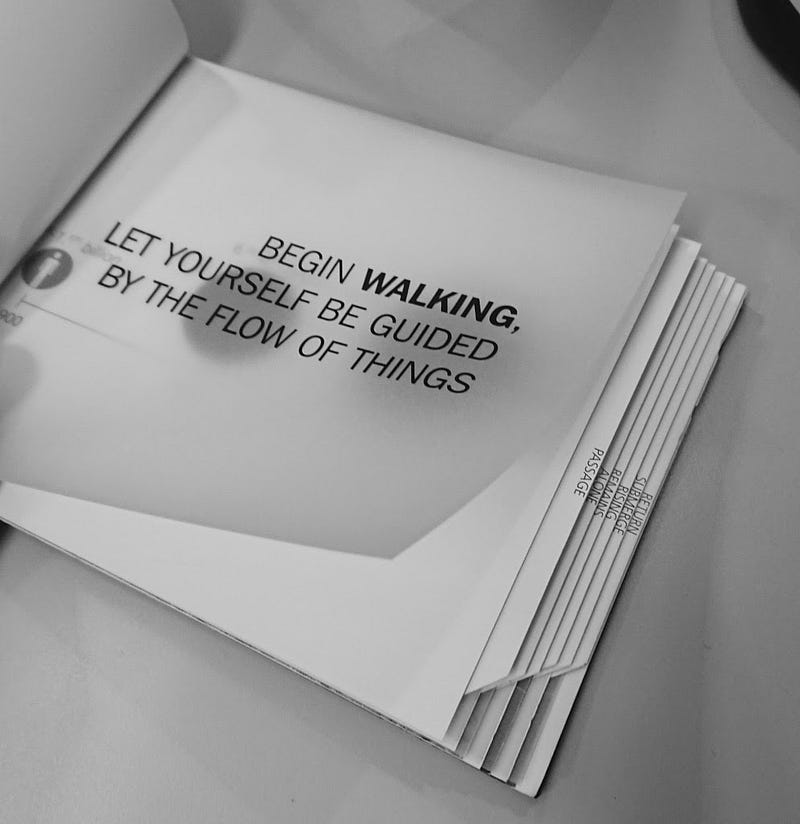

The piece itself has a number of constituent elements that are all continuously in conversation with each other. At the beginning of the experience, audience members are given a printed book, a set of custom headphones (with binaural microphones attached), and a small box on a shoulder strap. Inside the box are a Raspberry Pi computer, a PiSound sound interface and pre-amp for the microphones. Each section of the book has a one-word title, and the participant is instructed that when they hear a word in the headphones they should read that section. These are the only words they hear in the soundtrack. The sections of the book each contain a simple prompt, for example, “walk with the flow of the city” or “find higher ground.”

Only Expansion (2018) — case for

audio system, headphones with binaural microphones attached, guidebook

Only Expansion (2018) — case for

audio system, headphones with binaural microphones attached, guidebook Only Expansion (2018) —

instructions in the guidebook

Only Expansion (2018) —

instructions in the guidebookThe work is not site-specific; it is designed to be experienced anywhere. The prompts invite the audience to explore their surroundings, to seek things out not by looking at a mobile map interface, but to move by looking and listening, by feeling their route as a wayfinder, constantly engaged instead of just moving from point to point. Each prompt in the book is printed on transparent paper, and underneath there is some form of contextual information or image, such global shifts in temperature, increasing population, or rising sea levels.

These pieces of context are vague and poetic rather than didactic. Graphs simply show rising lines and avoid axis legends, quotes are given without source. The emphasis is on offering a signpost rather than an answer.

In the headphones the experience shifts between a variety of modes. At some moments the soundtrack is a rich cinematic score, blocking out external sound and casting the audience’s surroundings as an almost fictional space. At key points the microphones turn on and the sound of the world, along with the participants’ accidental or intentional contributions, is brought into hyper-focus (audiences have described it as akin to having super-powered hearing). In some sections, this live sound feed is processed to create musical contributions, so passing voices may become resonant harmonic tones or the drone of traffic might become a rhythmic pulse.

the listening of elsewhere

The live processing is also used to simulate different environments, for example, being underwater, muting, and echoing the sounds around. These periods of environmental processing are combined with field recordings from sites undergoing rapid climate change. So as you hear the real flood water rising in Louisiana you also hear it happening to the sounds around you. These moments create a complex layered experience of space, listening to a remote location while simultaneously tuned into your environment, and hearing that environment change as if the future was now. I want to create a connection between the here and there, the distant and immediate, letting you experience how they resonate with each other, while never allowing you to totally be in one or the other.

This entanglement is not only spatial, it is temporal. When we augment with pre-recorded media (in this case the field recordings) we are also combining two different times, the past of the recording and the present of the listener. In the evocation of oncoming climate change, we are also somehow suggesting a displacement of the audience member into their own future. I think this layering of different timescales speaks to something about our current ecological experience.

Morton describes global warming as a hyperobject, something so large it extends behind and ahead of us in time, something too large for us to fully comprehend. When we begin to move away from human exceptionalism and think of ourselves as part of something bigger, we have to become aware of timescales that exist both beyond and within our lifespans. From the incomprehensible arcs of geological time to the fleeting life cycle of a mayfly, from the way we live now in the shadow of actions taken by our ancestors to our children who will live in the landscapes shaped by our current actions.

the world is not for humans; it is, rather, with humans

Sound is an inherently temporal medium. There is no sound without an event and the following transmission and dissipation of energy over time. (Some would even argue that sound creates our experience of time.) In Only Expansion’ the relationship between experiencing multiple timelines is inextricably linked with my reason for using augmented audio, but sound offers something else too, something darker. There can often be an inherent ambiguity to sound: What is making that sound? Where is it coming from? For me, this sense of the unknown might offer a taste of horror.

While many eco-critical artworks and films show us the beauty and fragility of environments we might lose, I’m also keen to explore the darkness of what our future might hold. Combining the ambiguity with the viscerality sound offers might let us experience what the artist Anja Kanngieser describes as “registers that are unfamiliar, inaccessible, and maybe even monstrous; registers that are wholly indifferent to the play of human drama.” Maybe this layered and sometimes uncomfortable listening will allow us to step further away from the pedestal we seem to have created for our species, letting us fall deeper into the morass.

no vantage point

In conversation with Heather Davis in 2015’s ‘Art in the Anthropocene’, philosopher Bruno Latour argues that Gaia affords no single vantage point, and, as a result, we have been monstrously tricked by the comforting singularity of the point-of-view produced by NASA‘s image of our warm blue planet floating in the void.

If the story is one of entanglement of scale, from microbial to hyperobject and from the immediate present to geological or networked time, then to tell it, to understand it, we might need to develop new forms of attention. These forms of attention might not be subject-object contemplation, not human vs nature, but a tangled singular system — modes of attention that offer us the potential to trace these networks of entanglements, to not just see or hear about, but to actually experience the interconnectedness of multi-scales of agents and entities.

Immersion might mean looking outwards, listening outwards.

Immersion might just mean there is no vantage point.

Sections of this text have been adapted from the publication ‘No Vantage Point: Reflections, Provocations and Experiments in Immersion’, created as part of my Immersion Fellowship with the South West Creative Technology Network. A digital copy is available at duncanspeakman.net

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.