Not a Film and Not an Empathy Machine

How necessary failures will help VR designers invent new storyforms

With the arrival of the first generation of consumer headsets, virtual reality has produced a wealth of exploratory projects from a diverse group of very talented practitioners including game designers, animators, documentary journalists, Hollywood filmmakers, social activists, university researchers, and visual artists. Most of what these adventurous folks (myself and my students included) are producing is terrible, which is just as it should be.

Expanding human expressivity into new formats and genres is culturally valuable but difficult work. We are collectively engaged in making necessary mistakes, creating examples of what works and what doesn’t work for one another to build on. The technical adventurism and grubby glamour of working in emerging technologies can make it hard to figure out what is good or bad from what is just new.

As someone who has been practicing and teaching narrative design in new digital media genres long enough to have seen the phenomenon of over-excitement at a novel technology combined with design confusion many times before, I want to counter two of the most common confusions about VR. I also want to offer some illustrative examples of how to spot good design in the hope of speeding up the process of finding the lasting expressive strategies on which to build new story forms.

Confusion One: VR is not a film to be watched but a virtual space to be visited and navigated through.

Therefore:

- Please forget everything you know about composition that reflects the physical properties of film and screen-watching. This includes thinking of VR as “movies without a frame” or as having “edits” or as needing introductory titles and credits that play in real time.

- Please leave out anything that can be heard or seen that is not diegetically part of the virtual space that is the actual focus of your design. Everything the interactor sees or hears must be part of the space VR creates for them to inhabit. This means no voice-overs, no text overlays, no background music.

- Please omit any cuts or edits that are not the result of voluntary and conscious movement on the part of the interactor — whose sense of agency is the single most important design value in any digital artifact.

- Please remember Nonny de la Peña’s first rule of VR design: Begin by thinking of your body in the space. The focus of VR design is not the camera frame, but the embodied visitor.

- Please remember that sound design is your friend (as in film — here is the place for your training to kick in!) But it should be spatialized, dramatically: louder as you approach; surprising you from behind; cueing you to look left or right, and reflecting the materiality of the virtual world. The breathing of the bison in one VR travelog was the feature my students found the most immersive, and real audio is an important feature in the immersive power of de la Peña’s work as well.

Confusion Two: Empathy is not something that automatically happens when a user puts on a headset.

It must be produced as in any other story-telling medium by mature narrative techniques employed by skilled practitioners. The job for the present is to collectively invent those techniques. Therefore:

- Looking down and seeing breasts will not give males sudden insight into the experience of females.

- Showing people in sad circumstances via a headset will not make them any more or less relatable than showing them on TV or in photos in a newspaper. In fact, some 2D still photos are worth 1000 VRs.

- Instead of overhyping the inherent empathy-value of VR documentary, we should look for the specific moments that point to the genuine promise of the medium in creating compassionate understanding, and build on those.

For example:

A heavy relief package of food is dropped from the air seemingly at our feet, and a young man tries to lift it, triggering our desire to reach out and help. The experience of hunger and dependency is not narrated by voice-over but made concrete as we witness the physically challenging task of lifting this bundle, and experience the urgency of the need through the frantic activity in the field. Our clear positioning at the edge of the action prevents us from thinking we can interact with the food seekers, and it turns our inability to reach out to a particular person at a particular moment into a dramatically experienced desire to be of assistance to the hungry refugees.As in a good documentary the experience is encapsulated by one sympathetic boy’s efforts to find, claim, and carry one bag of food. This vignette, part of an uneven though well-meaning larger project on refugees, was all the more effective when it was released as a short separate experience because it is limited to this one dramatic incident, the arrival the food drop, which is immediately understandable on its own terms.

Empathy in great literature or journalism comes from well-chosen and highly specific stories, insightful interpretation, and strong compositional skills within a mature medium of communication. A VR headset is not a mature medium — it is only a platform, and an unstable and uncomfortable one at that.

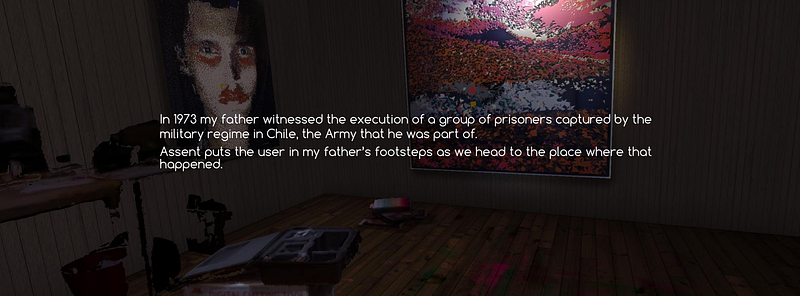

To invent a new medium you have to find the fit between the affordances of the co-evolving platform and specific expressive content — the beauty and truth — you want to share that could not be as well expressed in other forms. There is no short-cut to creating it. It comes from a long process of trial and error within a community of practice. But I am encouraged by such small moments of expressive power, and by the overall ambition of works like Oscar Raby’s who uses virtual reality to explore elusive and haunting memories of political violence, as well as by several experimental examples of the use of enclosed virtual spaces to reproduce the experiences of besieged and refugee people.

Learn more about Oscar Raby’s latest immersive

documentary

Learn more about Oscar Raby’s latest immersive

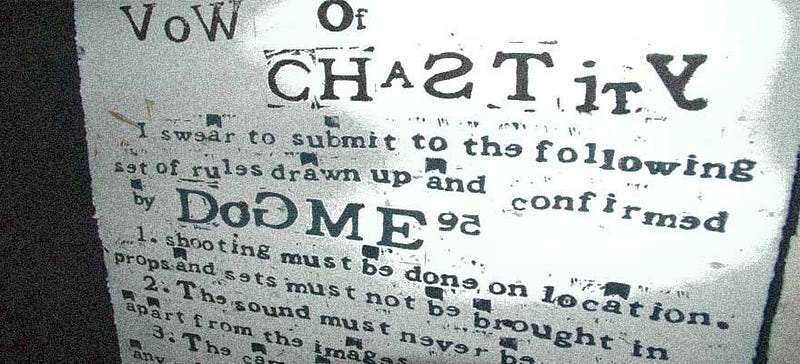

documentaryI am also inspired by the deepening in expressive interactivity in the relatively short time that VR has been practiced by professional journalists and animators. For example, Nonny de la Peña’s groundbreaking original VR project Hunger in LA, was a model of dramatic compression in its own right,but her more recent Across the Line moves the interactor from observer to enactor, from seeing a man collapse into diabetic coma on a food line to walking past a line of intimidating abusive demonstrators to enter an abortion clinic.

Want to

experience this game? You’ll need an HTC Vive

headset.

Want to

experience this game? You’ll need an HTC Vive

headset.There is a similar leap into dramatically effective interactivity between the Oculus Story Studio’s Emmy-award winning Henry — which presents us with a hedgehog we passively watch on an elaborately decorated set that we cannot explore — to the charm of the shy goblin in the recently previewed Gnomes and Goblins game, whose world is open to our exploration, full of secret places to peer into, and who is much more present in the space because he is responding the interactor in real time.

So I remain optimistic about the long-term prospects for VR storytelling, expecting the reliance on legacy media techniques and magical thinking about technology to fall away, as the exuberant creative process of collective invention continues to stumble forward toward more expressive conventions, formats, and genres, one necessary failure at a time.

Responses to this piece

Towards a VR Manifesto by Katerina Cizek

VR Is Not film, So What Is It? by William Uricchio

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.