Marshmallow

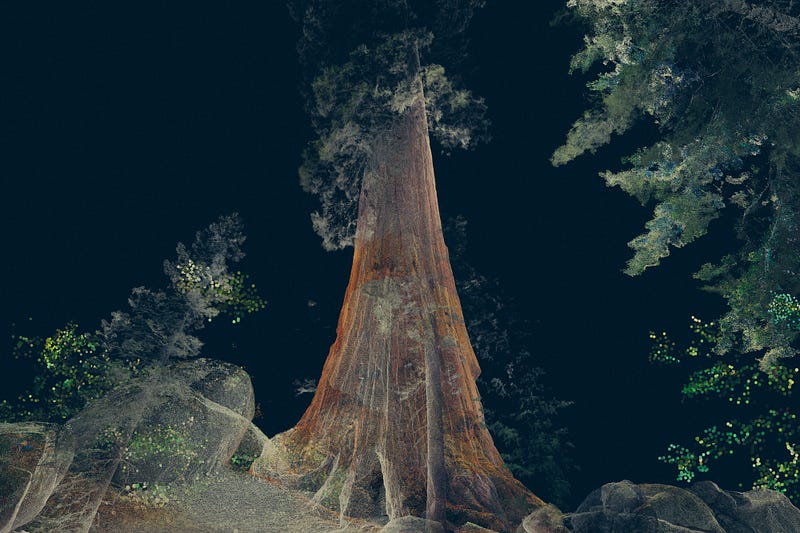

Laser Feast — In the Eyes of the Animal — Decimated Point Cloud, Stylised based on Dragonfly

Perception (Grizedale Forest 2015)

Marshmallow

Laser Feast — In the Eyes of the Animal — Decimated Point Cloud, Stylised based on Dragonfly

Perception (Grizedale Forest 2015)An Immerse Response

As practitioners of digital arts, our work is often bound to the lifetime of certain technologies. Whether online or offline, works become obsolete as soon as an update of the associated software or hardware appears.

“Preserving…has to start early, almost in tune with the creative process.” suggests Erwin Verbruggen in this month’s feature story. After looking at Erwin’s piece, I’d like to consider two aspects of preservation: preservation of the work itself by diversification across different platforms and preservation of the associated data. In our case, the second is perhaps more important than preserving the work itself.

We are a small group of people who go by the name of Marshmallow Laser Feast, an experiential studio based in London. We operate in the intersection of art, science and technology. Most of our work is driven by research and combines a wide range of disciplines including installation, live performance, and virtual reality — with the goal of exploring the world beyond our senses.

Our two most recent works, In the Eyes of the Animal and Treehgger: Wawona, both use a combination of LIDAR (Light Imaging, Detection, And Ranging), White Light scanning (WLS), Photogrammetry and the latest developments in VR. The primary purpose of both works is to serve as a window into unseen worlds, connecting us anew with the ancient, elemental systems we have neglected. A natural byproduct of the techniques used are the “digital fossils” of the habitats we captured and that have inspired us.

We use this term for two reasons. First, assets become effectively buried on our Dropbox as soon as a project is done. Second, digitizing fossils by using photogrammetry and CT scanning has been an important tool for scientists for last few decades. Although, our subjects are still ‘“alive” and not yet petrified, we are not completely certain they’ll survive another century.

Historically, advances in technology have taken us further away from nature. Though it may sound paradoxical, we believe that technology has reached a point where it can start to reverse the gap between ourselves and the natural world. With the rise of virtual reality as a medium, more and more people are exploring how to capture reality in new and innovative ways.

Scan of a

Giant Sequoia Tree from Sequoia National Park-2016 / Marshmallow Laser Feast / Treehugger :

Wawona

Scan of a

Giant Sequoia Tree from Sequoia National Park-2016 / Marshmallow Laser Feast / Treehugger :

WawonaDigital Archaeology

The success of an experiential work is mainly measured by its longevity and popularity — how many people does the work touch and for how long? An alternate measure of success is perhaps: How much does the work contribute to culture and science?

The locations we’ve been capturing for these projects, such as Sequoia National Forest, Bristlecone Pine Forest or Grizedale Forest, are of cultural significance. It is fair to say that in these uncertain times we don’t know whether these habitats will exist beyond the end of this century. Therefore, the data we’ve been gathering can be a useful repository for both science and education.

High-Detailed Scan of a Giant Sequoia Tree from Sequoia National Forest-2016 —

Courtesy of Scott Metzger

High-Detailed Scan of a Giant Sequoia Tree from Sequoia National Forest-2016 —

Courtesy of Scott MetzgerAs a studio, our current method of preserving data is limited to physical drives and the cloud storage on which the data is archived. Some assets make it into the final work, but most sit in the annals of Dropbox — the attic of the digital domain. We’re keen to explore how we can repurpose the assets of these unique environments. Much like we open source software and the tools we build, can we open source our assets for a greater good?

Many of us only realized the importance of ancient artifacts in Syria, Iraq or Nepal when they were destroyed by catastrophes or violence. It is shocking! Cyber-archaeologists responded swiftly and started making 3D models of the long-gone sculptures. In the wake of these events, it is good to think that the data we are collecting in making these projects can be used for preservation. This sparked the idea of seeing data as a form of conservation. Our data can live as a digital archive of the natural world. It is the least we should do. We should be doing much more.

We are in the early phase of scoping a simple roadmap to preserve, share and diversify the assets that have been captured.

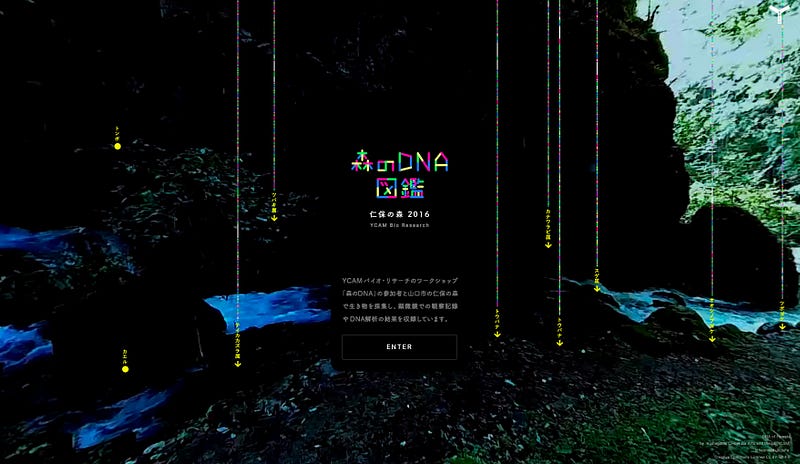

Y.C.A.M —

BioLab DNA of the Forest, Augmentation of In the Eyes of the Animal in Japan — 2016

Y.C.A.M —

BioLab DNA of the Forest, Augmentation of In the Eyes of the Animal in Japan — 2016DNA of the Forest

Here’s a brief case study for the conservation of a project through diversification of its formats:

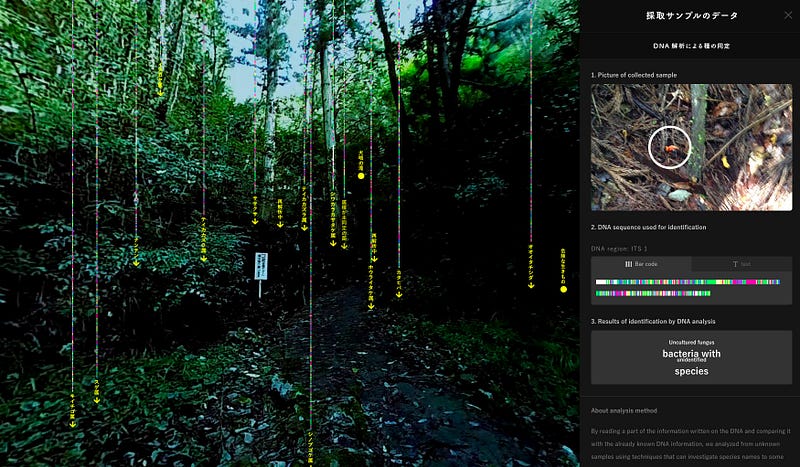

In 2016 In the Eyes of the Animal was exhibited at Yamaguchi Art Center (YCAM) in Japan. The team curated a program inspired by the VR piece, set locally in Nishimoto forest. Dr. Hiroshi Tanaka took participants on an expedition to explore the local ecosystem and inform participants how the local wildlife might perceive the world. In addition, participants were given a sampling kit to start collecting DNA from the forest, which was then analysed by YCAM’s bio-lab. This data has since been visualized on a 360 degree website as a catalogue of information, without a narrative, which can be viewed here.

DNA samples

from Nishimoto Forest in Yamaguchi Prefecture. DNA of the Forest, Y.C.A.M 2016

DNA samples

from Nishimoto Forest in Yamaguchi Prefecture. DNA of the Forest, Y.C.A.M 2016Using an experiential VR piece as a launchpad to inspire new perspectives highlights how data can manifest itself through various mediums. This can extend the lifespan of a project by branching it out.

This project also ignited the idea of using DNA as a form of data preservation. DNA is the most compact way of storing information, evolution’s own cloud storage. As funky as it may sound, storing information in DNA has long been the plan of scientists and some Silicon Valley start-ups. It is possible to store 2 petabytes (2 million gigabytes) of information in 1 gram of DNA—the equivalent of 100,000 submillimeter-accurate tree scans.

Currently, it costs around $10,000 to write and read 2 MB information, so we have a long way to go before the DNA writer/readers become affordable. In the meantime, we need to figure out the most convenient semi-apocalypse-proof way of preserving data for our cultural future.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.