A roundtable conversation with the creators of A DIY Guide to Proxy Protest on disability rights, interdependency and the politics of visibility

(A person

in a gray shirt whose phone is attached to their chest with a harness. The screen displays a blurry

image of someone’s face.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control Shift

(A person

in a gray shirt whose phone is attached to their chest with a harness. The screen displays a blurry

image of someone’s face.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control ShiftWe all have the right to protest. This action — to gather peacefully, en masse, on the streets whether in public solidarity for a cause or to publicly oppose, call for change or hold accountable — is so significant that its protection is written into the legal frameworks and constitutions of democratic countries. However, the right to protest is increasingly being curtailed. The UK Government, for example, is currently pursuing an anti-protest bill that would put severe restrictions on and criminalize protesting. The vocal opposition to the “draconian” bill demonstrates the need to be able to take to the streets but there are, and have always been, large groups of society that cannot attend these public events, regardless of the laws, even though they might have wanted to. For disabled people, protesting on the street is not always an option. Their voices and bodies can be rendered invisible, disenfranchised and depoliticized by the spaces and modes in which traditional forms of protest take place. Who gets to be seen and heard in public? Who has the privilege of moving through these spaces and who is excluded? Why? And, can this change?

These are some of the questions that Arjun Harrison-Mann, Benjamin Redgrove and Kaiya Waerea grapple with in their work around proxy protesting and the role of design in the disability rights movement in the UK. In 2020, they created A DIY Guide to Proxy Protest, which subverts commonplace technologies such as smartphones and video call software to enable alternative ways of protesting. It works through a collaboration between a proxy (or stand-in) who goes to the physical space of the protest and the protester who streams into the event and is rooted in the culture of DIWO (do it with others). The trio’s work straddles the line between practical solutions and provocations — as well as being useful objects, these tools also function to start conversations, tell stories and make visible those who are usually invisible.

I spoke to Arjun, Ben and Kaiya over Zoom and their care, thoughtfulness and commitment to creating access came across in the considered way they interrogated their own ideas, how they expressed themselves and how they talked to me and each other.

[The conversation has been edited for length and clarity and took place before the anti-protest bills began being discussed and passed in the UK parliament.]

(A person

tightening harness straps around their chest.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control Shift

(A person

tightening harness straps around their chest.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control ShiftLara Chapman: Please could you each tell me a little bit about yourselves, your design practice and your involvement with disability rights?

Arjun Harrison-Mann: We’ve started doing this thing recently where we audio describe ourselves, we think it is a way of giving a bit of context of how we identify ourselves and put ourselves forward. I’ll start by doing that: I am a tall skinny Indian man, although skinny is not happening so much since lockdown [laughs]. I have long hair with shaved sides and a gold nose ring. Today I’m wearing a burgundy shirt.

Ben Redgrove: My name is Ben Redgrove. I am a white Englishman who is missing the middle finger on my right hand. I recently shaved all my hair off, for the want of something better to do during lockdown and, as with Arjun, I seem to be going rather round [everyone laughs]. I’m aiming for a perfect circle.

Kaiya Waerea: My name is Kaiya, I am a young, white cis woman with brown frizzy hair which is tied up. I look tired and I’m wearing a scrunched up top and am bit disheveled today but that’s okay because no one will see me.

A.H-M: I began looking at disability rights mainly through my mum who is disabled and has had a history of experiencing the systemic disability benefit cuts within the UK. While I was completing my MA, the Tory government were implementing further cuts and, during that time, I started using design as a cathartic tool — a way of working through my feelings.

Ben and I have been working together now for about five years, looking at the role of design within the Disability Rights Movement in the UK. Our work is about making protest accessible and looking at the relationship between power and presence. Since then we’ve met up with Disabled People Against Cuts who are an activist group here in the UK. Through our friendships, with them and with various other people, we have been getting more and more involved. It is about friendships, relationships and being allies. It is also about the work that is unseen.

I think an important thing to note is that our work is grounded in the Social Model of Disability which is a belief that society disables people rather than that people are disabled. It refutes the medical model, which, in short, sees curing and correcting the functioning of an individual’s body as the main way of bringing about social integration of people living with various impairments and illnesses — which is inherently problematic. The social model instead sees the structures imposed by society as disabling, and something to be reimagined.

One of the key phrases in the disability rights movement is “nothing about us without us.”

B.R: We both come from a design-based background but I think there has always been this interesting and quite useful tension between our skills. I come from predominantly moving image, narrative-based and installation backgrounds, so I have been really interested in the image-making aspect of the things we do and how that takes on value — the power of imagery — as well as the more pragmatic design side.

K.W: I am a writer and designer and my practice is concerned with chronic illness particularly in relation to work, narrative and time. I am interested in forms of knowledge production and dissemination and in how temporalities are structured to oppress certain ways of being. I started to work through these areas because of my own diagnosis with a chronic illness. I think when Arjun talks about cathartic design, I really relate to that because there is this idea of “okay, this thing is really happening to me, what tools do I have to understand it?” and my own practice and research is the first thing I can reach. That has been a big part of me processing my own experiences.

I started working with Arjun and Ben about six months ago and that’s been a really exciting place to activate some of my concerns in a way that I just couldn’t on my own. The skillset of three expands what work is possible and we have quite a spread between us of technical skills.

L.C: Before we start talking about A DIY Guide to Proxy Protest, I thought it would be interesting to discuss the idea of DIWO (do it with others) that is central to your projects and, it seems, your process of working. What is DIWO? How and why do you apply it to your work?

A.H-M: DIWO is a really important part of our practice and a really important part of caring and thinking about access. It is a term that is used a lot in open-source movements and I think it exists to reframe DIY culture — this notion that we all have to do things ourselves, that we are all self-reliant and can self-teach.

Applying the DIWO mentality when thinking about access and activism is really important. One of the key phrases in the disability rights movement is “nothing about us without us.” Ben and I are allies to the movement so we are always making sure we are making things with people and not for them. It’s really important to acknowledge what is at stake when you have a very different lived experience.

L.C: Yes, I think the design industry is often guilty of not taking time or care to consider and forces solutions down people’s throats which aren’t really practical or created with empathy.

A.H-M: Yes, or solving the wrong thing…

B.R: I think that the idea of collaboration in our work is both a necessity and a political stance. I think the two come hand-in-hand. It is vital in this context as it is how you get things done and how you can work together to negotiate a potentially insurmountable situation.

You cannot come up with all the answers and there’s nothing wrong with that; there is something quite wonderful about needing other people.

K.W: Yes, and it is important in unsettling this idea of independence. Listening to you both talk made me think about the main disability benefit in the UK — the Personal Independence Payment. The point of that benefit is to make you independent which, of course, can be great and empowering but independence isn’t necessarily the marker of a good, fruitful and safe life. Being positively and mutually dependent on other people is actually a really important and amazing thing. I think that DIWO speaks to that notion that you can’t know and do and solve everything. You cannot come up with all the answers and there’s nothing wrong with that; there is something quite wonderful about needing other people.

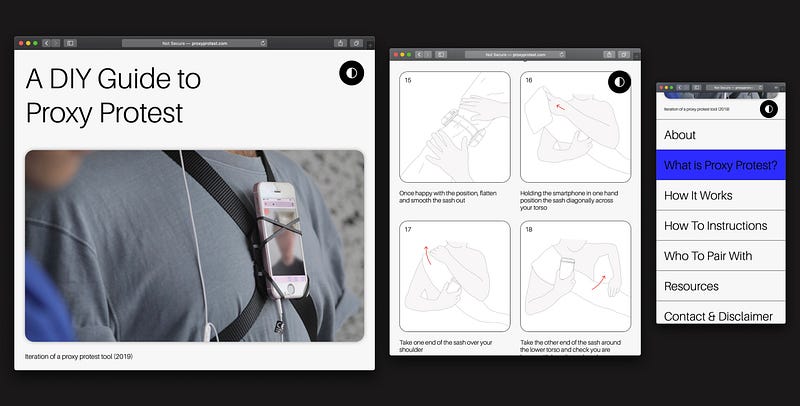

(Three

screenshots of the DIY Guide to Proxy Protest’s homepage, including an image of a harnessed phone, a

diagram on how to harness, and a list of alternate pages.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control Shift

(Three

screenshots of the DIY Guide to Proxy Protest’s homepage, including an image of a harnessed phone, a

diagram on how to harness, and a list of alternate pages.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control ShiftL.C: That’s a really lovely way of thinking about how we live and what we prioritise. DIWO is central to your recently published website/work/protest tool A DIY Guide to Proxy Protest which relies on the collaboration between two people. How did this guide and protest tool come about?

A.H-M: When we talk about proxy protest more generally, it is essentially a way of pairing one person who might not be able to leave their homes, for a number of reasons, and a person who is able to be at a protest in physical space and connecting them through live streaming and the subverting of ubiquitous technologies such as phones. It is about repositioning phones on the body to create a way in which you can move and act on behalf of somebody else.

More specifically, A DIY Guide to Proxy Protest is the most recent of our attempts at looking at ways that we can make protest accessible and reimagine what access looks like. We’ve been thinking a lot about the role of the proxy — the stand-in — in creating new ways of thinking about access and new ways of caring. What does it mean to act in tandem with another person and to have a different type of accountability?

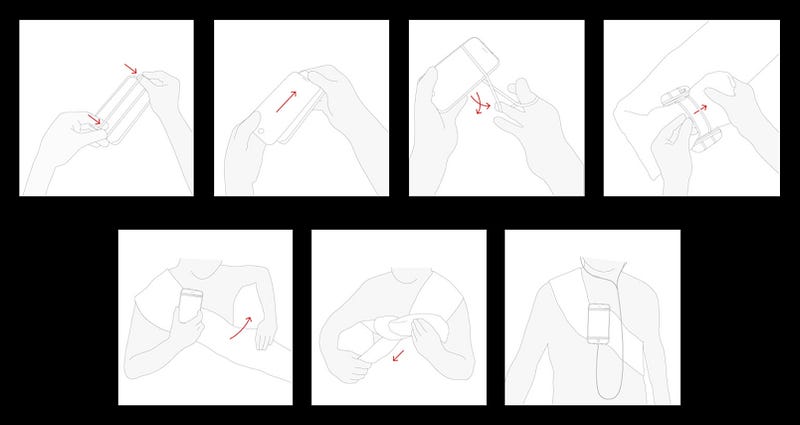

(A diagram

of 7 images depicting how to make a DIY harness for your mobile device. Elastic bands are stretched

across the smartphone and looped around a sash that is then tied firmly to the chest.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control Shift

(A diagram

of 7 images depicting how to make a DIY harness for your mobile device. Elastic bands are stretched

across the smartphone and looped around a sash that is then tied firmly to the chest.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control ShiftB.R: The original version and intention of it was to subvert that idea of a single, top-down surveillance camera — a body camera — and then this becomes a much more collaborative form of accountability. Not just that, but it becomes a way of negotiating space as a duo which I think is quite powerful as an action to do with someone else.

(A phone,

with wires connecting to a portable charger, harnessed to a person’s chest.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control Shift

(A phone,

with wires connecting to a portable charger, harnessed to a person’s chest.) ProxyProtest.com, Supported by Control ShiftL.C: Does it also intend to start a conversation with other people at the physical protest about living with a disability? I ask because there are certain design decisions you’ve made that seem to facilitate this, for example, the camera could just face outward so that the person streaming into the protest isn’t visible but you have chosen to show the person on the screen.

…often, wider systems and governments diminish a person’s visibility as a way of marginalising them…

A.H-M: When we think about making spaces exclusive and accessible, visibility is a really important part of that because often, wider systems and governments diminish a person’s visibility as a way of marginalising them. So, one of the things that the proxy tool tries to do, and the reason it is important to have the person visible at a protest, is about reclaiming a sense of power. There is an assumption that being present in a space has a power with it, so how do you reimagine that? Another part is about encouraging that dialogue, it can be quite hard to have this kind of dialogue and forms of engagement with people purely from screens so what happens when you make that a performative action? What happens when you embody that?

K.W: I proxied for a member of Disabled People Against Cuts [DPAC], at an event that Ben and Arjun did with the Serpentine Galleries called The Power Tour in 2019. I was there physically with my phone attached to my harness through which the person I was paired with was streaming virtually.

It was very moving for me to take on that direct responsibility of another, being a sort of surrogate for them in those physical places for others to interact with. Because they were visibly present on the screen, it wasn’t just between me and him, other people were approaching me and talking to him through my body.

B.R: I proxied at a protest outside Facebook’s headquarters in central London. I think one of the strongest things, as Kaiya really nicely articulated, was that feeling of being a conduit, of facilitating interactions between a mass of comrades, a mass of friends.

For me, there was a level of intensity from the members of security, who themselves had body cameras. I remember there was this strange feeling of them being quite confrontational, assuming that I was recording and then me trying to explain that that wasn’t the case. I also felt quite empowered because I was acting on behalf of another, or we were acting as a two, so I felt able to stand in that position in a much stronger way. That’s not to say that I was doing anything out of the ordinary but there was definitely a different feeling of empowerment and feeling watched over.

A.H-M: When you are in these experiences, it is quite vulnerable for all involved. I think that is a really powerful thing.

B.R: The other side of that is the aspect of negotiating the mechanics of being a proxy — what you’re standing in front of, making sure that you move in a certain way and taking care in how you move.

Although, we don’t want to fetishise the technology or think that it will provide us the solution of a platform that means we don’t have to worry anymore. I think the important thing is how you have to shape yourselves into specific circumstances in order to better converse, better negotiate or come to a greater understanding together, rather than assuming that will be done by some kind of machine.

A.H-M: It is about this balance of what we need in terms of technology to make spaces accessible and what we leave to how we perform. Recently we’ve been thinking more about how you can also act in a way that is accessible and inclusive.

…it is not so much a product, it is more of a provocation. We’re trying to make very ubiquitous materials defamilarised as a way of provoking thought.

B.R: I think that is a really important part of it because ultimately, and we’ve tried to do that with the DIY guide, it is not so much a product, it is more of a provocation. We’re trying to make very ubiquitous materials defamilarised as a way of provoking thought.

L.C: There is an interesting tension between private and public spaces that operates in all your work, but especially this idea of navigating protests from the space of a home via a digital medium. Could you speak about what “public” means to you and the proxy tool?

K.W: I think that the idea of public and private in relation to political action and politics is super dangerous because it sets up a dynamic where that which is public is political and that which happens in private is apolitical. Johanna Hedva speaks about this really well in their essay Sick Woman Theory. If actions have to be public to be deemed political then whole hosts of people are depoliticised with disabilities by not being able to get their bodies onto the streets. That is what the Proxy Tools start to address: how can these bodies also be on the streets?

I think that there is also something to be interrogated further within these categories. In a time of wide image sharing and video calling and the different ways that we can enter each others’ spaces, I think that public and private becomes what you share online and what you don’t share online. I don’t think those barriers are as physically spatial as they once were. They are more visual-based.

L.C: That’s really fascinating. Towards the end of what you were saying I got the sense that you think we might be moving in the right direction where those boundaries are breaking down, or do you think we are still quite stuck in that idea of private and public as separate?

That is what the Proxy Tools start to address: how can these bodies also be on the streets?

K.W: I wouldn’t say that we are moving in the right direction… I think that there is a really urgent tension that is caused by cultural representation becoming separated from political representation. We need to look at what it means when it feels like things are getting better because people are more represented in cultural spaces but actually that isn’t reflected in turn through political representation. This can feel confusing, contradictory and misleading. Political representation often seems like it happens publicly but it actually happens privately, in meeting rooms and closed-door spaces. I think that re-examining the locations of “the public” is a really important thing in relation to disability because so much of one’s experience as a disabled person has to happen in private spaces because of how public spaces are designed.

B.R: There’s definitely something in what you were saying, Kaiya, in that the relationship between public and private takes on a very specific form in terms of disability. I hadn’t ever thought about the bringing of private spaces into public or the convergence of those two things, which is essentially what the original Proxy Tool does.

A.H-M: When Kaiya talks about Johanna Hevda and their main provocation of “how do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you cannot leave your bed?”, that really talks well to this idea of public and private.

…who are we talking about when we talk about “the public”? Is it those that are visible? I think that is probably the case a lot of the time.

First of all, who are we talking about when we talk about “the public”? Is it those that are visible? I think that is probably the case a lot of the time. Also, it’s interesting to ask: do we ever feel like we are members of the public? Who are we addressing and why? Why are we making certain things public? Who already has the privilege of being part of that public space? These are all provocations that don’t have particularly easy answers but they are things we need to work through. I think to make something public means to make something visible again. There are many ways that we can use that word but for me, it always comes back to visibility.

To make something public is to evidence it, so we need to be aware of the politics of doing that. What do we need to evidence and what do we not? What do we need to make visible and what do we not?

(A person in

an outfit of metallic pink, blue and neon yellow, who’s attached an iPhone to their chest with chain

mail. The screen of the iPhone displays another person with a DSLR aimed at the phone camera.)

Perspectives on Visibility,

2020, Sky Cubacub, Sandra Oviedo AKA

Colectivo Multipolar, Arjun Harrison-Mann, Benjamin Redgrove & Kaiya Waerea, commissioned by

Control Shift — photography by Sandra Oviedo AKA Colectivo Multipolar

(A person in

an outfit of metallic pink, blue and neon yellow, who’s attached an iPhone to their chest with chain

mail. The screen of the iPhone displays another person with a DSLR aimed at the phone camera.)

Perspectives on Visibility,

2020, Sky Cubacub, Sandra Oviedo AKA

Colectivo Multipolar, Arjun Harrison-Mann, Benjamin Redgrove & Kaiya Waerea, commissioned by

Control Shift — photography by Sandra Oviedo AKA Colectivo Multipolar (An image

of a person with a cane in an empty warehouse in Camberwell, framed by another image of a seascape

in Cyprus.) Perspectives on Visibility, 2020, Ebony Rose Dark, Arjun Harrison-Mann,

Benjamin Redgrove & Kaiya Waerea, commissioned by Control Shift

(An image

of a person with a cane in an empty warehouse in Camberwell, framed by another image of a seascape

in Cyprus.) Perspectives on Visibility, 2020, Ebony Rose Dark, Arjun Harrison-Mann,

Benjamin Redgrove & Kaiya Waerea, commissioned by Control ShiftAuthor’s note: Arjun Harrison-Mann, Benjamin Redgrove and Kaiya Waerea have recently begun applying the proxy protest tools to other scenarios which we also talked about in-depth. In particular, they have collaborated with disabled artists to create a series of short films called Perspectives on Visibility. It looks at the nuances of visibility and access under lockdown and tries to acknowledge that a lot of the conditions that we find ourselves living with right now, under the pandemic, are the conditions that people who are disabled have been living under for a long time. They are collaborating with artists Sky Cubacub who is part of the Radical Visibility Collective who focuses on radical visibility and the marginalisation of LGBTQ+ disabled people; Ebony Rose Dark, a visually impaired black drag queen who makes work around seeing and being seen; And Sophie Hoyle whose practice explores an intersectional approach to post-colonial, queer, feminist, critical psychiatry and disability issues. I encourage you to watch the videos here.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.