An interview with artist Rachel Devorah

Rachel Devorah is an MIT Open Documentary Lab Fellow, sonic artist, and technologist whose works engage the poetics and politics of their specific context. MIT Open Documentary Lab Producer Claudia Romano spoke with her about her inspirations, her trajectory as an artist, and her explorations of the mediated body and femininity in her work.

photo of

Rachel Devorah by Danielle Judith Zola Carr

photo of

Rachel Devorah by Danielle Judith Zola CarrCould you tell me about yourself and your trajectory as an artist?

My principal medium is sound, but often sonic digital and emerging media. I teach Electronic Production Design, the creative coding classes, at the Berklee College of Music, and teaching informs a lot of my artistic practice. I am interested in the technological context of a work as well as the work itself. What does it mean to use different types of technologies to make a work? What does it mean to use different kinds of technologies to disseminate a work?

What led you to sonic art specifically?

I have a music conservatory background. I’m a hornist by training and studied composition at Mills College in California, which is an amazing hub for experimental music and also went to library school. I learned how to code as a librarian and that got me working in electronic music.

Could you tell me a bit about your most recent projects and how you incorporate the human body into your work?

Our perception of the world is largely based on our bodies. One of my early composition professors, Jeff Nichols, taught me that you could only make art for yourself. So, I make art for myself and that is totally egotistical, but it’s also an acknowledgement that I can’t understand where any other body in the world is coming from.

Why has the body become an object of inquiry and mediated platform for exploration in your artistic practice?

I’m really informed by feminist performance art from the ’70s. I came across the work of Carolee Schneemann and her piece Interior Scroll. I read that work as an expression of the fact that, as a woman in the ’70s, she couldn’t help but make work about the body.

Carolee Schneemann was like, “You’re going to see me as something that’s birthing stuff, you’re going to see me as sexualized, so I might as well birth my art and be naked at the same time.” But look up the poem she read during the performance. Interior Scroll is not just about the spectacle of her body, it’s about her making an artistic statement and seeing if the spectacle of her body distracts from the statement that she’s making, which I think is really interesting.

There are so many places where society tells me that my selfhood is wrapped up in my body. Like Schneeman, I feel like I have to make art about my body sometimes because so many around me are putting their own meaning on the meaning of my body and my selfhood.

I’d love to hear more about all of that in the context of your most recent projects. Can you talk about Radiant Drift?

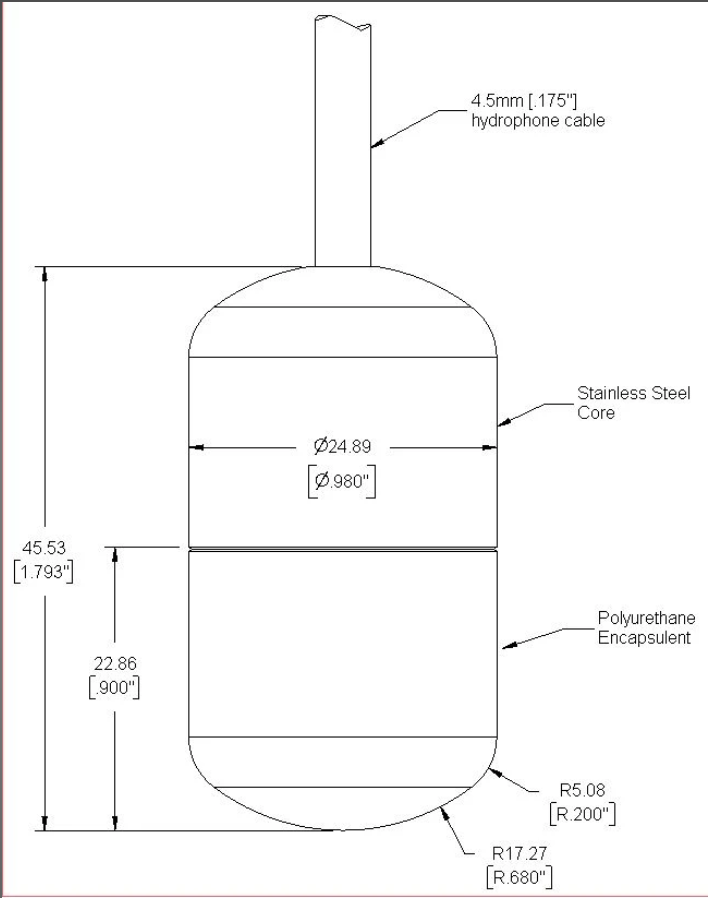

Radiant Drift is an immersive audio work that uses hydrophone recordings I made on my cervix while pregnant. After the birth of my daughter, I made field recordings of her voice in air. The work is a collage of the hydrophone and field recordings, spoken personal narrative, and electronic music.

I am not going to make art all of the time about being a parent now because that’s not all that I am. But I felt compelled to make art about this change; becoming a parent. Then I thought about what unique experience I was having or could have in terms of sound relative to gestation. I thought, “Oh, I have a hydrophone and I know how to use it.”

Hydrophone design

Hydrophone designDuring your presentation about this to OpenDocLab, you talked about some of the reactions. Can you share more about that?

A female-presenting body in public is always vulnerable to the public thinking that it’s theirs to do what they want with it. A visibly pregnant body is especially vulnerable. People just love to try and control a visibly pregnant female body. When I was [audio] recording my gestational process, I told some people that I was recording with a hydrophone in my vagina.

People started saying that it was essentially unladylike and telling me that it was possibly dangerous for the baby. I stopped telling people what I was doing because people had such strong opinions and they were trying to control me and what I was doing with my body.

How do you respond to something like that?

I tell them they don’t have the right to say such a thing. I often hide behind my educational privilege and tell them I have a Ph.D. and that I am an expert on feminist electronic sonic art. I wonder how I could do that in a less privileged way.

Well, you are an expert on this topic and your body.

But every person is an expert on their body. How much, at all, should my broader expertise matter? What does the privilege of that expertise have to do with the privileges of my socio-economic background? My whiteness? I shouldn’t falsely gild my right to do as I choose with my body with broader expertise when everyone ought to have it. It seems like I could be contributing to harm.

I read the story of Serena Williams giving birth in the New York Times. It’s a really harrowing account of what it’s like to be a Black woman and pregnant in the U.S., even under some of the most — in some ways — privileged circumstances. Serena Williams is absolutely the most qualified person to speak about the condition of her body because it is her body but also because, as the world’s greatest athlete, she is literally the world-wide expert on what bodies can do.

When she was pregnant and having complications with the birth, she was telling hospital staff that she was having pain in her legs. They didn’t believe her.

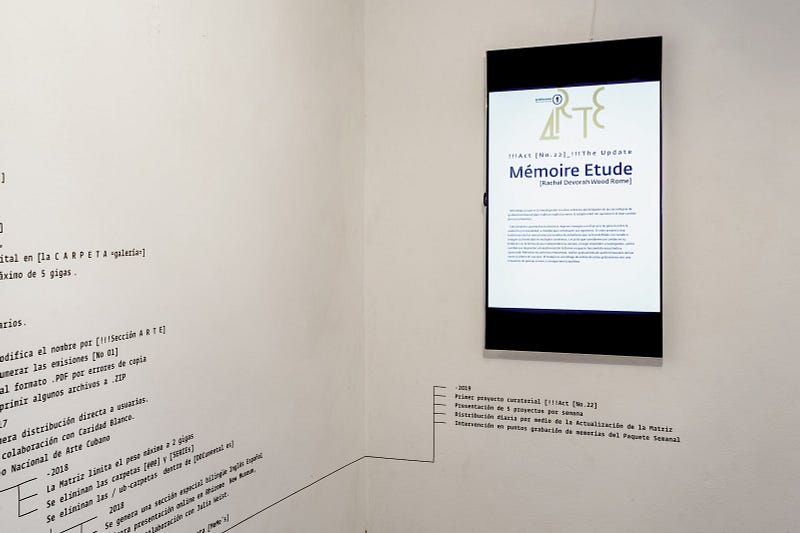

Another project that comes to mind when I think about your work related to the body is your project Mémoire. Could you speak to that?

Sure. That is something that I’ve been developing for about a year. I’m interviewing different people who have had experiences of femininity across different contexts. I interview women who are migrants, transgender women, etc.

I make video recordings of just their eyes, then I make audio recordings from my own ears using binaural microphones so that I’m giving the perspective of my body watching and listening to the women speak.

Mémoire

Installation

Mémoire

InstallationYou’ve mentioned you used binaural recording to create Mémoire and a couple of your other projects. Why use this technology?

Because I think it acknowledges the subjectivity of the creator and that all art is subjective. I think that acknowledging the subjectivity of the creator makes space for acknowledging the subjectivities of people engaging with the work and acknowledging a plurality of subjectivities. It’s acknowledging how different people are.

So it lets the viewer experience what you’re actually hearing, your subjectivity.

Yeah. I like to try and minimize how much I’m telling other people what to do.

What do you think about the relationship between our bodies and corporations trying to capitalize off of us? Is this something that you think about in your artistic practice?

Yes, yes, yes. I don’t use any technologies that I don’t understand intimately. I’ve not necessarily made every piece of hardware and software that I use, but I understand it to a degree that I could reproduce it. That’s a very intentional choice on my part. Then I try and pass on that understanding, and make the work that I’m making, and make the technology that I’m using to make my work as accessible as possible. Then I can explain it to my seven-year-old niece and my grandmother and anybody who wants to know.

It seems that in a lot of your projects like Radiant Drift and Mémoire, you’re particularly interested in mediating women’s bodies and exploring femininity. Why do you focus on this in particular?

I think that femininity has a lot to do with how I experience the world. Nothing more than that. We’re raising my kid, Wendy, as a girl. If she is not a girl, she can tell us. There’s a lot of beautiful things that I’m excited about sharing about femininity with her but I don’t think that gender in her generation is going to be anything like what it was in the context that I grew up in. I recognize that gender is socially-constructed and always evolving. I’ve made what work I can make with the context that I was coming from. But, I look forward to being challenged on future contexts about how gender is continuing to evolve.

Do you have any other projects on the docket right now? What are you doing next?

I perform in a live improvised electronics duo with my friend Seiyoung Jang. We are both using homemade electronics. Again, getting back to this idea that I only use technologies that I understand really intimately, that’s part of our practice. We’re both improvisers and love making art in the moment. We have a show with Non-Event in Brookline on January 14th, 2020.

In the spring of 2020, I have an installation that I’m doing with the Boston Center for the Arts (BCA) called Siren, which will be a 2-channel audio installation which mixes the sounds of an EMF meter monitoring the 5G tower in front of the BCA with hurricane warning systems in real-time. I’m doing this because the FCC has auctioned off our means of detecting hurricanes, and I want to bring attention to this issue.

What do you hope your audience will take away from your work?

I really liked Andrew [Demirjian]’s response to this question during his talk the other day. I’m going to steal it, with credit! He said that you just want to offer to people that there’s a different way of looking at the world, or a different way of listening to the world — a different way of thinking about what is going on. I think life is a gift and you make art to offer your perspective and extend the possibilities of that gift.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.