“Real Solidarity” Isn’t the Problem— Effective Action Is

An Immerse response

Image by

Seymour Chwast from The New

Yorker

Image by

Seymour Chwast from The New

YorkerIn late 2010, pundit and popularizer Malcolm Gladwell dismissed the power of social media as a tool for mobilization in an article titled "Small Change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted.” Gladwell’s argument was simple: real change requires protest in physical space, which requires people to take risks. People only take risks when supported by their strongest ties, close friends and family, not the weak ties that social media encourages and enables.

Gladwell’s article is useful in that it’s a compact summary of a popular argument against digitally driven “armchair activism” or “slacktivism.” For critics like Gladwell, the model for social change is the American Civil Rights movement. It involves in-person confrontations between brave protesters and dangerous authority figures and ends with the passage of laws to protect human rights.

Gladwell’s article is also wrong. His argument is based around sociologist Mark Granovetter’s seminal paper, The Strength of Weak Ties. The second half of Granovetter’s paper is a case study of two activist efforts to challenge gentrification, in which the effort driven by strong ties fails and the one built around weak ties succeeds. Despite the appeal of a narrative in which successful activism is based on high-risk personal involvement, Granovetter makes a convincing case that what really builds movements is reaching a wide network of people who can mobilize to take a variety of actions, not just public protest.

When we speak of “real solidarity” and define it as something that takes place in “real life” or “away from the keyboard,” we’re restricting our understanding of social change in ways that delegitimize some of the most interesting activism taking place today.

When Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, media outlets turned to Facebook to find images of the young man. Many used an image in which Brown was shot from below, making him look especially tall, and scowling. Some reports characterized the peace sign he’s displaying as a gang sign.

Activists noted that other images of Brown were available on Facebook and wondered why one that portrayed him as threatening was chosen instead of other contemporaneous photos that depict his youth.

African-American twitter users began posting pictures of themselves from social media, showing pictures of themselves in a positive light (graduating from college, giving speeches, in military uniform) and in negative lights (making rude gestures, drinking, smoking). Accompanying the pictures was the hashtag #iftheygunnedmedown, short for “If they gunned me down, what picture would they use?”

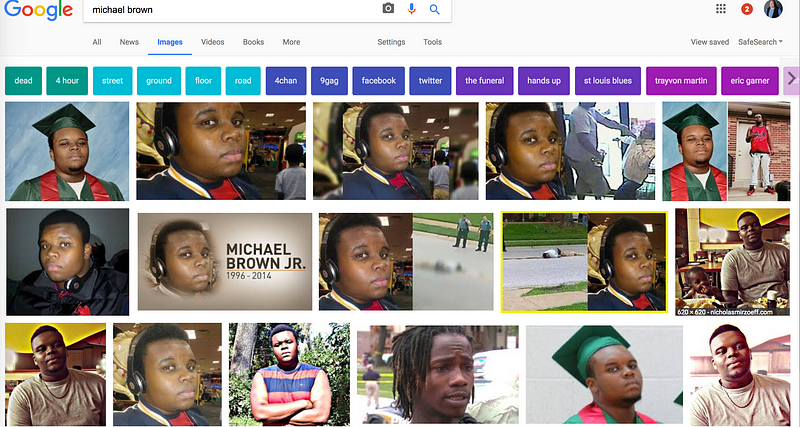

Within a week, over 110,000 users had participated in the hashtag campaign, filling a Tumblr with the meme. NPR and the New York Times reported on the campaign, and media organizations quickly stopped using the original photo of Michael Brown and chose either one of him in a graduation gown, or in a photo where his youth is more apparent. A search for Michael Brown on Google Images shows how much more prominent these images are than the one initially used to portray Brown:

#iftheygunnedmedown is clearly an act of digital solidarity. While it didn’t drive people into the streets, it was deeply effective. Activists realized that the problem of police violence against people of color is in part a problem of perception — some law enforcement officers perceive men of color as older than they actually are, and as potentially dangerous figures. When the media portrays victims of a crime using imagery that makes them look dangerous, it reinforces this stereotype. #iftheygunnedmedown effectively persuaded some newsrooms to look at the imagery they use and make more responsible choices.

Understanding how digital activism works requires letting go of our preconceptions of how social change works and considering a wide variety of pathways to change. Demanding that digital activism lead people to physical presence at marches and rallies presumes that occupying public space is the only way to make change. Research by media scholar Zeynep Tufekçi suggests that public protest is actually less effective in a digital age, precisely because it’s easier to drive people into the streets through social media than it was when we relied on analog organizing. Authoritarian leaders like Recep Tayyip Erdogan are learning to ignore these protests because they know they won’t lead to them being ousted from power, Tufekçi argues. Rather than demanding activists behave the way we expect them to, we’d do better to learn from the ways they’re already finding to be effective.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.