On the politics of public spaces, documenting protest movements, and AR as a way of healing collective trauma

I first met Lara Baladi in 2014, when she started her fellowship at the Open Documentary Lab. She arrived from Egypt with an extensive, somewhat unwieldy, archive from her participation in the Egyptian Revolution in 2011 that she wanted to make accessible. Titled Vox Populi, Tahrir Archives, this web-based timeline of the revolution and its aftermath is both a transmedia series of artworks and an open-source portal into archives related to Tahrir Square and other global social movements. It continues to evolve.

While she was at the lab, Baladi collaborated with another fellow, Halsey Burgund, to make a project called Invisible Monuments, a geo-located contributory audioscape. It uses Roundware, an open-source app created by Halsey, that enables people to listen to geolocated audio clips seamlessly and contribute their own.

Baladi and Burgund started in Dewey Square, Boston, the site for Occupy Boston in 2011, the same year as the Egyptian revolution. People could walk around the site and, with their cell phones and the Roundware app, listen to other’s memories and comments about Boston Occupy or add their own. It is a living monument to Occupy Boston and, by extension, to protests around the world.

As the ODL embarked on an initiative focused on augmenting public spaces and places this past year, I remembered this project and decided to sit down with Lara again. Her first public space artwork dates back to 2001 when she commissioned Egyptian cinema painters to hand-paint giant billboards and place them in strategic spaces in Cairo, including Tahir Square. The billboards, which promoted her gallery exhibit, posed provocative questions to viewers, unwittingly making them participants in her show.

What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Borg

El Amal (Tower of Hope), ephemeral architectural construction and sound installation.

Grand Prize, Cairo Biennale, Egypt. Photo Lara Baladi, 2008.

Borg

El Amal (Tower of Hope), ephemeral architectural construction and sound installation.

Grand Prize, Cairo Biennale, Egypt. Photo Lara Baladi, 2008.Immerse: Why don’t you start by describing your work in public space?

Lara Baladi: My most renowned artwork in public space is Borg El Amal — in Arabic, the Tower of Hope — which, in 2008–2009, received the Grand prize at the Cairo Contemporary Art Biennale. The tower was inspired by the architecture of the slums around Cairo, more commonly known as the ‘Red City.’ With a small team of young architects and local workers, we built a three-stories-high tower in situ, in the garden of the Palace of Arts, on the Opera House grounds. This military base in the center of Cairo, one of the highest and most expensive pieces of real estate in the city. A couple of weeks before the opening, I was asked to cover the growing structure before Mme Mubarak, the wife of former President Hosni Mubarak, was coming to inaugurate the film festival. The director of the opera was worried she would be shocked by the construction site since this type of architecture represented a negative image of Egypt. The Red City at the time constituted 65% of the surface of Cairo.

When the Biennale opened, the Donkey Symphony, a sound piece composed for the project, played in a loop inside the tower. Initially criticized, Borg El Amal generated all sorts of incredibly positive responses.

A few years later, Tahrir Cinema and Radio Tahrir were initiated during the early days of the revolution, in the midst of the 2011 uprising. Tahrir Cinema was set up in Tahrir Square using a makeshift screen. Overnight, it became a significant space for people to gather and watch videos of testimonies, clips from the Arab uprisings and more. Both Tahrir Cinema and Radio Tahrir — one of the first free FM radio stations in Egypt — were direct responses to the events unfolding on the ground. These two projects were unique in how they emerged spontaneously and grew organically and in how my interactions with the public, with the protesters, were unforgettable.

Immerse: Is this when you started building the archive?

LB: I had started collecting data seven months earlier but Tahrir Cinema is when I first curated screenings using my nascent archive. This month of nightly projections confirmed to me the importance of archiving the revolution. Tahrir Cinema served as a way for people to share and exchange footage of various battles and events they had witnessed around Cairo and Egypt. They downloaded their footage onto our computers and we uploaded some of our footage to their USBs. The point was to disseminate video clips from Suez, Alexandria, Cairo, and other governorates as widely as possible. We offered protesters’ first-hand accounts and narratives of the revolution, thus countering the mainstream state media propaganda.

Tahrir Cinema, Tahrir square, screenings in situ, July

2011 sit in. Cairo, Egypt. Photo Sherif Gaber, 2011.

Tahrir Cinema, Tahrir square, screenings in situ, July

2011 sit in. Cairo, Egypt. Photo Sherif Gaber, 2011.Immerse: When you think about the elements of public space, how do you integrate architecture, people, and sounds into your work?

LB: While the foundations of Borg El Amal, the Tower of Hope, were planted strategically in the Opera House grounds, government-run space, it was a direct comment on the state of poverty around the city. The work also addressed the way the informal architecture of the Red City had destroyed the flat and green landscapes along the Pyramids Road. The Donkey Symphony, playing in the heart of Cairo, echoed cars honking, calls to prayer and other soundscapes.

In 2014, during an art residency at Art Omi (Hudson Valley, NY), I staged the Donkey Symphony in another type of tower, an abandoned silo in the middle of the countryside. The piece acquired a whole new meaning as it resonated against the rusted walls and merged with the sound of the rain falling on the roof. Borg El Amal was a “monument for the poor,” to quote a friend, and the Donkey Symphony is at once a cry of despair of the Red City and a cry of hope.

Immerse: How did your work evolve after you moved to the US?

LB: When I arrived at MIT in 2014, as part of the fellowship with the Open Documentary Lab, I began to explore new technologies and investigate the state of digital archives. The augmented sound art piece that Halsey Burgund and I collaborated on, “Invisible Monument,” was one of my first experiments with storytelling using these new digital technologies. Halsey Burgund improved and upgraded the version of the Roundware software he had previously developed and I curated the data. People could then listen to the augmented narrative and contribute to it by uploading their footage or by recording a voice testimony. From there on, my work took a new direction, integrating both analog and digital technologies as well as embracing further their relationship to the Internet as an archive, as an art space, and an agora (a space for dialogue and encounters).

Immerse: Did Invisible Monument get a lot of audience interaction?

LB: I had just moved to the US, so I hardly had a network. Occupy Dewey Square had lost its momentum and there was a big strike on the day of the opening; most trains were cancelled. Basically, only a few people were able to join but in spite of the low attendance, it was technically successful. It inspired me to further explore how in the future we could continue to occupy spaces if not physically, at least virtually, especially when these spaces are controlled. It was also a great experiment in terms of leaving a trace of such a significant political moment as Occupy Boston. Dewey Square was a pilot project for thinking of ways of recording history and extending the project to Tahrir Square.

Immerse: Can you talk about that a little more? What exactly is your approach to recording history?

LB: Roundware is a downloadable app available both for Android and iPhone. The footage I curated had been recorded in Dewey Square, in Tahrir Square and during other Arab uprisings and protests, including Occupy Movements. The sound bites initially produced by mainstream media, by citizens (using camera phones), by artists (songs, parodies), and by media activists (testimonies) were mapped out along various paths throughout the square. As users walked around with the app on, they could hear sound bites according to their geolocation. This first layer of “recorded history” was the foundation on which to build more layers, personal accounts, and testimonies, creating over time an “Invisible Monument” and tribute to a historical event.

Immerse: What does it add to the experience of listening to these histories in this public space in Dewey Square versus in your living room?

Invisible Monument invitation, September 30, 2015. Copyright

Lara Baladi and Halsey Burgund, 2015.

Invisible Monument invitation, September 30, 2015. Copyright

Lara Baladi and Halsey Burgund, 2015.LB: These spaces are very charged with historical moments that a lot of people have experienced and now share and remember. While we didn’t have many people come to the opening, those who did had been very involved in the Occupy Boston movement. If we return to a place where we have experienced something major such as a trauma, our cellular memory is automatically triggered. We remember the trauma and therefore we can start the healing process. Spaces with emotional anchors invite us to transcend our history, individually and collectively. There is still a lot to be learned as to how new technologies can be applied to making therapeutic art.

Immerse: How would you define public space?

LB: Because of everything we are discussing here, the word agora immediately comes to mind. Agora is the Greek term for a place of assembly. It’s a place where democracy can grow, where artistic, political, and spiritual ideas are shared.

Immerse: So it’s not about an actual physical space, because there are places where people can gather but cannot protest?

LB: Public spaces hardly exist in autocratic regimes. When they do, they are highly controlled, not only to avoid the sharing of information and political ideas but also to avoid the physical assembly of people, which can lead to protests and marches.

When the uprising started in Egypt in 2011, Tahrir Square became a place of protest, a space for exchanging political views. Tahrir Cinema helped catalyze conversations. It offered a space that was not available on that scale before. In the “Tahrir agora,” people of all walks of life found a common ground and the possibility to express themselves and hear each one another.

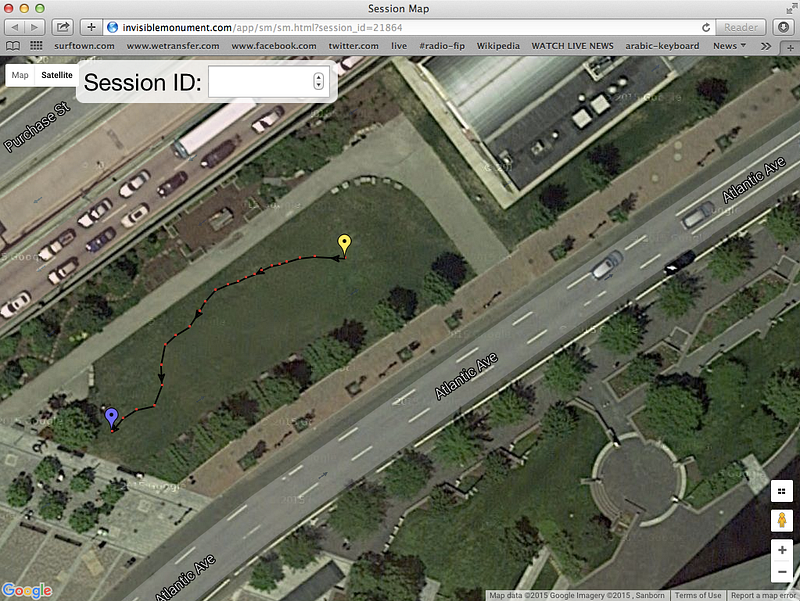

Path of a

person experiencing Invisible Monument in Dewey Square. Copyright Halsey Burgund,

2015.

Path of a

person experiencing Invisible Monument in Dewey Square. Copyright Halsey Burgund,

2015.Immerse: What do you think AR can do best?

LB: As I was saying earlier, I believe AR can play a big role in collective trauma healing. But I would add that augmentation is best used in projects that respond to political constraints, in places where freedom of speech and public spaces are limited, and in educational projects aimed at facilitating access to knowledge, to archives, and to other data sets.

Immerse: That isn’t visible to the authorities.

LB: The peer-to-peer technologies, the access through various apps, the invisible nature of augmented reality projects complicate their surveillance.

Immerse: Would you consider your work to be augmenting reality?

LB: If we think about the words “augmenting reality,” as opposed to AR technology, then, yes, I would say that my work, and art in general, augments reality. The process of making art is an act of synergy. It implies assembling, connecting, layering, ideas, objects, and data, which together equal more than the sum of the individual parts.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.