A conversation with new media artist Grayson Earle on participatory politics in transformative media, transparency in screen-based works, and digital liveness

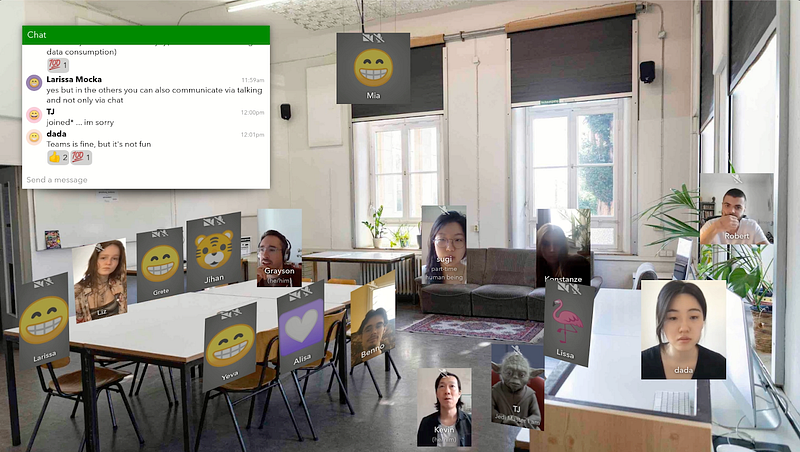

Screenshot of Grayson Earle’s

visit to the Media Innovation and Disruption Colloquium, taught by Kevin B. Lee at the Merz

Akademie, on the digital meeting platform ohyay

Screenshot of Grayson Earle’s

visit to the Media Innovation and Disruption Colloquium, taught by Kevin B. Lee at the Merz

Akademie, on the digital meeting platform ohyayThere’s nothing like a pandemic to produce strange proximities. In late 2020, new media artist Grayson Earle started a residency at Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, Germany, the same city where I teach. The pandemic had forced my school to close its campus and so I had to teach online from my apartment in Berlin. Throughout this time I wondered what the Stuttgart experience was like for Earle, having relocated from a prolific and well-established practice in New York City to a residency period coinciding with an extended lockdown at an institution already renowned for its seclusion (not for nothing is it called Solitude).

The start of 2021 brought exciting signs of Earle’s activity, with two new videos presented by MAX Media Art Xploration. In the desktop documentary Why Don’t the Cops Fight Each Other?, Earle investigates his own inability to modify the relationships between police officers in Grand Theft Auto V, inadvertently uncovering a virtual “Blue Wall of Silence” that protects the police as “immutable property.” The video demonstrates how the elements that are unchangeable are the most revealing about the ideologies governing the gaming environment. In his video essay Usefulness of a Useless Neural Network, Earle uses machine learning to perform absurdly rudimentary calculations, demystifying the aura of machine learning algorithms. In both instances, questions of accessibility and agency in relation to programmed systems are refreshingly presented through demonstrative and conversational modes of address.

In this spirit of showing and telling, I invited Earle to my online course “Screen Stories Live and Alive” at the Merz Akademie. The course is a follow-up to one on desktop and smartphone storytelling I taught during the first COVID wave in spring 2020. As the pandemic dragged on, I became more occupied with questions of life and experiences of liveness within the online environments we’ve been ushered into during the pandemic. How can digital experiences be seen as a new mode of cinema in the post-cinematic era, as well as propose new possibilities for living?

I applied these questions to my design of the course, rejecting Microsoft Teams, the anodyne online platform adopted by Merz Akademie, in favor of ohyay, which had been celebrated among my friends since its appearance at the International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). The platform enables users to import their own images to create custom environments, placing visitors in a more immersive and contextualized surrounding than the prison-grids of Zoom or Teams. Within a simulated ohyay version of a Merz Akademie classroom, I welcomed Earle to discuss his work with my students, and he reciprocated the interest by asking questions of mine. The resulting conversation looks at our respective work in coding, video essays, and desktop cinema not just as artistic and critical practice, but as modes for producing digital life. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Kevin B. Lee: This morning our class looked at Why Don’t the Cops Fight Each Other? The work is transparent; it gives an idea of what your intentions are, as well as your process. Maybe it would be helpful to get an idea of your background with GTA V and how you stumbled upon this particular issue?

Grayson Earle: I learned about this mod, called Deer Cam, which I can paste in the chat. Someone had modified GTA such that the main character was replaced by an automated deer, which roamed around the game world. Sometimes the cops would be called on the deer for running into someone. GTA is such a rich simulation, so injecting some absurdity or looking into the assumptions that went into creating what we think of as a realistic urban simulation became very interesting to me. I started working on my video around the time George Floyd was murdered by the police. I was trying to just make a piece where the cops would beat each other up continuously, as a form of catharsis.

I quickly discovered that it was not possible to make cops fight in GTA 5. The problem consumed me for weeks, until I finally decided to go step by step and apply the scientific method to this investigation. I looked into the code that comprised the police officers. I pored through every single property that you could possibly think of to change. And eventually came to learn through a conversation with one of the people that develops the tools for modding GTA data that it is actually an immutable property — the police will never fight each other in the game. And so, of course, I had to make something about this, because it’s so fascinating on a political level that the software is projecting certain assumptions of society into this simulation space.

KBL: We’re talking about this particular work the day after the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin’s murder trial. One significant way this trial broke with prior cases is the lack of a “blue wall of silence,” the silent code that cops always have each other’s back, and they’ll never testify against each other, and so on. We saw the Minneapolis police chief testifying against one of their own. So what’s happening in real life, in this case, is something that even it’s not possible in Grand Theft Auto V. Where’s that coming from? Is it self-policing?

GE: It is unprecedented, a real indication that the tireless work of organizers has worked. As for GTA, I think that it was more a subconscious projection into the game space that no one intended to happen. On one level it betrays more of our societal psyche and certain inevitabilities, whether that’s capitalism or policing — there’s a lot of problems with the GTA world beyond the police. The only eventuality in the game is to commit crimes, kill people, accumulate capital, and then buy more things.

KBL: An important aspect of your work is how you engage the community in the making of the work. In the video, we see you pose the question “why don’t the cops fight each other” on a very active modding forum. In their answers, it just seems like they’re almost purely concerned with the technical implication of this question, as if they don’t catch the subtext. But to me, that’s the thing that came out first, asking what that’s about on a social level.

GE: This is something that strikes me about your piece, Transformers: The Premake, which was clearly the inspiration for mine. It goes beyond talking about the thing — how these flows of capital and international politics and social media intersect to produce a new sort of mass media monster — and moves into reaching out and touching the thing itself. One of the ways it does this is by transgressing the studio’s draconian copyright policies and the other is by engaging a community on YouTube to start to formulate a kind of opposition to these practices.

KBL: Right, well I have to confess that the community engagement piece, which is so integral to Why Don’t the Cops Fight Each Other? from start to finish, didn’t really factor until towards the end of the making of Transformers: The Premake. At first I thought it was enough to just create a counter-image of the production. That was more of an Adorno/Frankfurt School and Harun Farocki-inspired approach, to stand outside of the object of study. But at some point I just realized that so much of what I was working with was drawn from this participatory culture that the likes of Henry Jenkins have exalted, and I had to ask myself if my own practice needed to engage along those participatory terms. Maybe it’s like describing the difference between a critic, which is a reactive stance, and someone who is more of an activist.

I wouldn’t say that The Premake is an activist work, but it certainly brought to mind the possibility of engaging in activist media in ways I hadn’t previously considered when it came to making video essays or desktop documentaries. And this is something I really admire about your work, because you’re a coder, you’re a gamer, and you’re obviously very familiar with the technical side of gaming and digital culture. At the same time, you have a very strong activist background. You were involved in Occupy Wall Street, so it goes back quite some time. I’m curious to know how you think these two roles have related to each other over the years. Has the relationship between them evolved for you?

GE: I kind of dabbled in street art as an undergrad. I was embarrassingly bad. When Occupy Wall Street came about, like you said, I had already been messing with computers and stuff. I came across this group that had just formed, called The Illuminator. They were using this van with a super powerful projector on top to project political messaging or images onto buildings. And so I joined that crew, which was helpful for them, because I had technical know-how and could help with projection mapping. The fact that I couldn’t draw or paint no longer mattered, because all of a sudden I could just program something and then project that onto a building.

In my project, Bail Bloc, cryptocurrency mining is utilized to bail people out of jail who couldn’t afford to do that otherwise. I see technology as a way of outpacing our adversaries. It’s illegal to put a political message on a wall with paint, but it’s not illegal to do that with a projector. With cryptocurrency, we could take a volunteer computer and make it generate real money without doing anything. I think I am always looking for opportunities to get into that new territory that disrupts what people think is or isn’t possible.

I’m curious about your take on this because you basically pioneered a genre, which must have been an incredible amount of technical work in the beginning. I must have re-shot the GTA piece four times because I kept making mistakes with capturing the video, or using the wrong resolution, or whatever. Are you also using scripting or programming or is it all painstakingly recording your desktop, looking at the footage, going back?

KBL: It’s all kind of a flowing jumble. Once I realized that it was possible to tell the production story of Transformers just by navigating through clips and websites on my desktop, on the one hand it was frightening because there was no specific model for what I wanted to do, although there were at least three works, all recently produced at the time, that were key reference points for me: Apple Computers by Nick Briz; Grosse Fatigue by Camille Henrot, and Noah by Patrick Cederberg and Walter Woodman. From what I could tell, none of them generated desktop environments via programming or elaborate post-production in After Effects. For the most part they are straight up recordings of their desktop. Recording my desktop was as much as I could manage at the time, and even now I prefer to keep it fairly straight as far as capturing what’s actually on my desktop and not dress it up too much in post-production.

It may also have to do with one’s relationship to “professional” film and media production practices and how one ties this novel form of desktop production to something that can bear some professional legitimacy. This has become really key especially in the past year with Covid, with desktop and smartphone films becoming more of a practical necessity. But I find myself less engaged with these concerns and more drawn to the question of authenticity. The desktop method presented itself to me as very natural and authentic to my experience of encountering and moving through the material of Transformers: The Premake. It was a matter of restaging and reenacting my previous online searches. It was a way of turning these moments of discovery into a skill that was organically self-produced.

I think this can bring us back to your work with GTA in terms of what kinds of fulfillment, creative or critical or whatever, one can enact within this platform. I think about this term “modding” as the main type of creative expression by the so-called “end user” or player. But I’d like to think of modding in a broader sense, through playing the game. I’ve seen this, for example, in the work of the Total Refusal Collective. But do you think there’s an important distinction to draw between coding and playing as far as fully realizing the potential of one’s engagement with a platform?

GE: I think it depends. When we use pre-made software to create art, we get boxed in. Photoshop has a very particular design philosophy that orients people to create images in a certain way that have a certain aesthetic, for example. That said, some things are only possible through play, like Eva and Franco Mattes’ Freedom, in which Eva as the player asks others in a Counter-Strike multiplayer game not to kill her, pleading that she is an anti-violence performance artist.

To the broader question of how necessary it might be for new media artists to code, one answer is that maybe we should be teaching everyone to code, or at least to have some kind of idea of what it is they’re looking at when they look at code. Thinking about cryptocurrencies and blockchain, I can imagine a future in which all contracts exist within various automated software systems, meaning that government and business documents and contracts of all kinds will be literal code. People will need to be able to read that.

But that’s also not a very satisfying answer. I don’t actually believe everyone should learn how to code. I think we should learn how to grow and cook food, but when I make tools I try to do so with the idea that there should be no real barrier to entry.

KBL: Do you always have this connection between the virtual and the physical, that they’re somehow always in dialogue with each other?

GE: I also think of the internet very much as a public space that has been more privatized over time. You could think about it as parcels of land, with various domain name extensions upon which we can settle or lay a claim. There are even ways of contesting the ownership of a domain name. You could DDoS attack Visa.com, and then all of a sudden, no one can get to their website.

Whereas if you just want to put one single noncommercial thing into public space, you have to go through the trouble of getting an Occupy Wall Street collective with a $30,000 projector to do that. And the people who lord over visual space are gonna get mad at you.

The Protest Generator goes back almost ten years, it’s now in version 3.0. The first version of it was made in Montreal, where there were massive student demonstrations in response to the government raising tuition. As a result the city made a law that more than 50 people protesting at a time had to get approval from the police. They were giving people $500 fines for violating this order. Once they banned protests, they increased tuition. And so we showed up with this tool. It was a way of projecting more than 50 people into public space as an intervention against the intention of that law, which is that they don’t want people to produce a spectacle by demonstrating.

Years later we were asked to do a show as a collective in a gallery at Colgate University. The idea with the gallery version is you walk up to the installation and draw a protest sign with a marker, put it on a scanner, hit scan, and then you would see a 3D avatar walk on screen holding whatever sign you had produced. Over time you start to see the politics of the people who had visited the gallery, rendered and put on display there. More recently, this tool has become more useful in some ways. It has been used in a couple of recent demonstrations, including at the University of California, in a series of demonstrations to get cops off campus. It’s being used virtually so that people can draw the signs on a browser and still be somewhat present or have their voices heard in a projection on the ground. That was really handy to have during a pandemic.

It looks like your students are using it now. I’m seeing pictures of cats and stuff coming in, which is cool.

Drawing of cat by a student on the

Protest Generator

Drawing of cat by a student on the

Protest GeneratorWe are both political artists, you and I. Don’t you think?

KBL: I come from more of a film criticism and cinephile background, and political activism is something I’ve had varying degrees of proximity to over the years. I did take part in demonstrations against the Iraq War back in 2003 and 2004. And it felt so futile when Bush was re-elected. I was really depressed. That may be why I sat out Occupy Wall Street. And now here I am, living in Germany, and I find myself in a Black Lives Matter protest in Stuttgart of all places, the Mercedes capital of the world.

After George Floyd’s murder, I’ve felt a much stronger urgency to connect my filmic pursuits to political awareness and action. It sort of gets back to the question of how we define “modding:” is it strictly in the hands of someone doing the coding, or can a player be a modder? I ask myself what it means to ascribe activist qualities to my activities, especially in relation to what others are doing. My most significant activity after Floyd’s death was co-curating the Black Lives Matter Video Essay Playlist, where we crowdsourced recommendations for over a hundred video essays relating to the movement.

I won’t make any claims for how useful it was for others, but for myself the project not only helped me educate myself on the issues at stake, but also raised a lot of epistemic questions about what types of media could be considered political or essayistic. We were looking at memes, TikToks, and a whole range of Black and POC expressions that pushed categorical boundaries and devised their own codes and languages. And within the context of Black Lives Matter, they gained political significance — not just for their content but a diversity and ingenuity of forms that was itself a political manifestation.

In that way it also challenged my relationship to cinema, which has been as complicated as my relationship to politics. I started as an indie filmmaker (to use the ’90s term du jour, which now sounds dated), then that activity stalled and I got into video essays as a way to keep producing in relation to cinema, while still holding cinema in the highest regard and hoping that the video essays that I and others made could be seen as cinema in their own right. But the works in the BLM playlist really had me wondering, do these new forms need to be labeled “cinema” to be valued? Even the way I just said that puts cinema at the center, which I don’t think is accurate anymore.

GE: I feel like it’s important that we both come from filmmaking in this sense. I don’t usually make films, but I came from the study of cinema. And in this field there is an acknowledgement that all cinema is deeply political. To some people this is a strange thing to hear; how can a Christmas movie or a teen movie be political in nature? But, of course, the Christmas movie is not only about consumer spending, it is intended to increase it during the holiday season, and teen movies in the ’90s and 2000s were basically reinforcing patriarchy and toxic masculinity through homophobic and sexist jokes. So, sometimes I resent this label of “political artist” or that we need to make additional justiciations for our work because we acknowledge that it is political. Painters selling their work to private collectors are extremely political: they are participating in financial capitalism to an extreme degree.

KBL: That speaks to how the political gets commodified, which may also inform some of my longstanding ambivalence with adopting “political” as a label to describe myself. To use that word to describe oneself or one’s work is to create an image, and then it’s a question of what that image does or what gets done with it. It reminds me of being at that Stuttgart BLM protest; at first, I was really excited to see so many young people there, including my students. But at the same time, I saw some of my students on Instagram judging each other, like she’s only there for the selfies. This wasn’t even something that I’d be thinking about back in 2003. Now there’s this layer of mediatic representation that seems inextricable to political activity these days, and how that’s being transacted in a marketplace of social value. It does feel like neoliberalism having the last word, putting even more expectations upon us to perform and finding more ways to divide us as to unite us.

GE: Do you know the artist Taeyoon Choi? He works in New York and developed these protest robots during Occupy Wall Street. I think about them often — the robots were holding signs that say “absence is presence with distance.” There’s another group, the Institute for Applied Autonomy, who’ve also developed protest robots. There’s one that’s a remote controlled car that has five spray cans on the back. It drives through public streets, writing messages anonymously. There’s another robot that hands out Marxist literature on the sidewalk, which I really love.

KBL: That raises a whole other set of questions about technological facilitation and automating or outsourcing your political labor to technological surrogates. Do you think that kind of misses the point?

GE: There is something poetic about it, which is that automation has been used historically to take rights and resources away from working people. I kind of enjoy subverting automation as a tool for workers.

I think a lot about accessibility, especially given the brave new world we’re living in where everything is online. I have to imagine that for someone who’s visually impaired, for example, all of this stuff that we’ve been using is really inaccessible, right? It’s not as though there’s an option built in, for example, for the written chat to be sonified.

KBL: That implies a sense of inherent possibility to the digital. For me, this class was kind of a survival tactic, because it’s now my third semester of teaching online. I just couldn’t do any more desultory Microsoft Teams or Zoom meetings as we normally experience them. I need to experience living. If I’m going to spend half my day in front of my screen, I need to turn this into a mode of life that really works for me. It’s about seeking platforms and interfaces that make that living possible, but perhaps more importantly, also seeking methods and tactics for how to live inside of them.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.