Part 5 in a series by Kamal Sinclair

So, an opera singer, creative technologist, trans activist, game designer, performance artist, artificial intelligence engineer, augmented reality empath, ambient data storyteller, speculative smart jewelry crafter, drone operator, cirque choreographer, robotics dancer, filmmaker, Afro-futurist hyper-reality maker, iOT installation architect, and bio-hacker walk into a bar.… No this is not the beginning of a joke, it’s what happens at the annual New Frontier Alumni Social. — Copy from the 2018 New Frontier Alumni Social invitation

In 2011, I had the life-changing opportunity to attend the inaugural New Frontier Story Lab at the Sundance Institute as a Fellow; thus began my love affair with this invigorating community. Every year since I’ve been fortunate to see that community grow to become increasingly inclusive of new people hungry to connect with others from different fields of knowledge. After so many years of being part of an intersectional community, it was hard to hear that my experience may be a major anomaly.

In the February 2018 installation of Making A New Reality, we outlined concerns with silos, groupthink, and knowledge ghettos that negatively impact equality in emerging media.

2012 New Frontier Story Lab @

Sundance Institute

2012 New Frontier Story Lab @

Sundance InstituteIn this March edition, we are sharing potential solutions, as identified by interviewees. When asked, “What could bridge the gap between the arts, humanities, technology, business, and policy communities?” they responded with the following:

- Promote the intrinsic value of each other’s sectors

- Create shared language and practices

- Invest in hybrid talent

- Strategically embed artists with technologists and scientists

- Thoughtfully include the arts in spaces of power

- Build interdisciplinary community outside spaces of power

Some interviewees gave great examples of organizations that are bridging these gaps and supporting the rigorous integration of diverse fields of knowledge in the creative pursuit of emerging media and meaning, including Eyebeam, National Film Board of Canada Interactive, Eyeo Festival, Allied Media Projects, Grey Area Foundation, New Inc., MIT’s Open Doc Lab and Media Lab, i-Docs, IDFA DocLab, Thoughtworks Artist Residency, IDEA in New Rochelle, Iyapo Repository, Indigenous Futures, Stochastic Labs, Tribeca Film Institute Interactive, USC School of Cinematic Arts and USC Game Innovation Lab, World Building Institute, BAVC, Carnegie Mellon, Columbia’s Digital Storytelling Lab, NYU ITP, Games for Change, Brooklyn Experimental Media Center, and Firelight Media, just to name a few.

My hope is that we can replicate and amplify these models, as well as develop new models that can implement the interventions articulated by the interviewees. Perhaps we can re-ignite a robust culture of intersectional and inclusive imagination.

Conversations with Bina

48 — Image from Eyebeam

Assembly

Conversations with Bina

48 — Image from Eyebeam

AssemblyPromote the intrinsic value of each other’s sectors

One strategy proposed by interviewees focused on advocacy within each sector to promote other sectors and raise critiques about siloed environments. For example, in engineering, tech, and science silos, educate people on the value of the arts and storytelling — i.e., art serves as:

- a mirror of society,

- a means to celebrate and interrogate the state of the world,

- a means of examining the inner and outer life of the human condition,

- a means of imagining complex possibilities and the spectrum between good and bad, and

- a means of informing our future design and societal choices.

Conversely, in the arts and humanities silos, educate people on the roles and processes of the engineers and technologists — i.e.: rigorous scientific and optimization methods help us:

- unlock the potential of the resources around us,

- solve problems and ease pain thresholds, and

- Invent ways to make the “impossible” possible.

Create shared language and practices

Gamemaker and filmmaker Navid Khonsari suggests re-educating technologists and creatives, so they can have shared language and at least a foundational understanding of their respective fields. “The technologists are strictly looking at what’s in front of them and how to take that hardware and software and expand it to give the creators or developers more liberties. And that’s fine, but it’s still going in one direction. I think you really have to attach the education of these two different sectors, so that they can come together as one, rather than trying to work independently. All we come across are technologists that need creative, and creative that need technologists, and I don’t hear about that anomaly that brings these two together so they’re working cohesively. That’s the key for the independent voices, and I think that’s the key for actual real success — to start breaking barriers.”

Yelena Rachitsky of Oculus points out one model for promoting collaboration across these sectors. “I’m working with Carnegie Mellon and I really like the system that they have for breaking barriers between disciplines. They put people in groups of 4 or 5 that include a designer, a director, a coder or engineering person, and a producer. They tell them they’re all equal to each other, that everyone’s opinion is just as valued as the other opinions. I love that model… I think the first part is bringing awareness and creating systems that are integrated from the beginning, like the CMU program. ”

Invest in hybrid talent

Many interviewees called for the establishment of a culture where individuals are rewarded for being well-rounded in the arts, sciences, and technologies. We should encourage artists to study science and technology, technologists to study arts and sciences, and scientists to study arts and technology.

Luke DuBois of the Brooklyn Experimental Media Center talked about the need to support people grounded in media, art, and technology practices: “James George is a really interesting guy because he gets it. He’s one of those people that are deep in the tech, but he’s fully aware that the way it’s deployed in mainstream industry is fraudulent. There were a lot of things about his project CLOUDS that I loved, but one was they were at least functionally aware of the need for diverse voices. I think James is a pretty honest partner in that he can be an ally, and I think there are a lot of people in the quote unquote creative tech space who are fully primed to help, they just need to be leveled up so they’re more visible.”

Maybe these gaps between technology and the arts will organically disappear as new generations of tech-savvy people emerge in the arts. Of course, our education system will have to provide the structure to cultivate those hybrids in a meaningful way.

Strategically embed artists with technologists and scientists

There are city governments now, like in Mexico City, that have cross-sector teams of artists and technologists. They are given a collaborative, shared office space, and, when there’s a civic problem, that creative team is activated to build some new code, to write a new algorithm, to create a story-driven campaign, to connect people to services, and to make life better in that city. That’s a model that needs to be replicated and supported [elsewhere]. We just did a whole series of labs that put scientists, artists, and social activists together that proved the model as well. We need to start telling these stories of artists being at those tables. — Wendy Levy, Executive Director, The Alliance

Interviewees also advocated for embedding artists and humanities scholars in tech centers. This is not a new idea. Artist and educator Marisa Jahn shared a book she authored, Byproduct (2010, YYZBooks), that outlined a robust culture of artist residencies and fellowships embedded in science and technology institutions in the mid-twentieth century. She noted that despite the resurgence of embedded residencies today, the history is under-chronicled, which can lead to organizations wasting cycles by reinventing the wheel. Some interviewees who have served as artists-in-residence recently complained that the current implementation practices made them feel like tokens with no real opportunities for collaboration or integration.

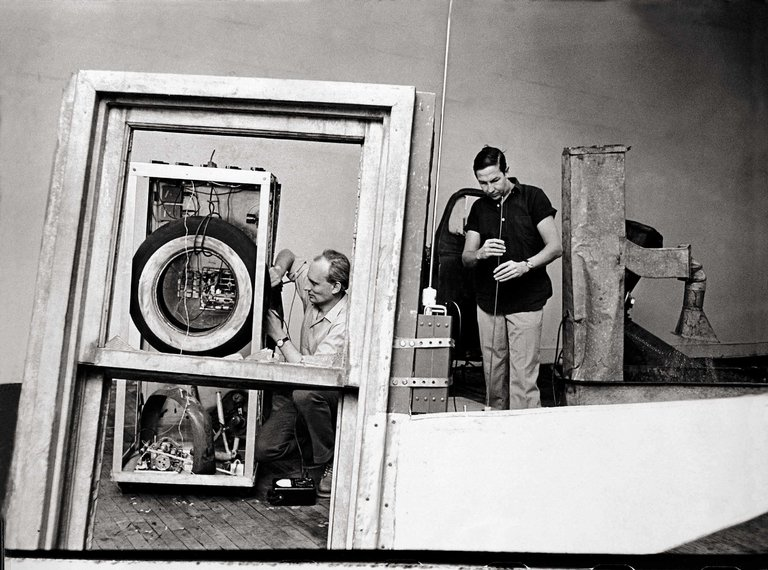

Billy Kluver, left, and Robert

Rauschenberg in Rauschenberg’s studio working on “Oracle” in 1965. (Larry

Morris/The New York Times)

Billy Kluver, left, and Robert

Rauschenberg in Rauschenberg’s studio working on “Oracle” in 1965. (Larry

Morris/The New York Times)“The late 1960s was a really utopic moment characterized by risk taking and cross-collaboration, when we saw a handful of science and tech institutions embrace collaborations with artists,” says Jahn.

“Some of the better-known ones include Xerox Parc, Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT, when Robert Rauschenberg started working with Billy Kluver from Bell Labs, and Artist Placement Group (APG). Founded by Barbara Steveni and her partner, John Latham, APG spanned more than two decades and placed more than1,200 artists in government, science, and industries. Around 1991, APG got absorbed by the British government and it kind of exists in a less edgy way. APG is less well-known to American artists, although now that they’ve donated their archives to the Tate they are gaining a bit of well-deserved currency. In the U.S., Mierle Ukeles was an artist embedded with New York City’s Sanitation Department for several decades. Her work has really helped embedded practices receive more attention,” she continues. “These are North American and European examples of embedded art practices. in the Global South, there isn’t a divide between art and life, so embedded practices are less binary. A common reaction is, ‘Well, of course, we’re embedded in society. Of course, we’re socially engaged.’ ”

Re-igniting the ethos of cross-pollination by embedding artists in tech, business, policy, and science environments might help us develop shared language and innovative visions of how to use emerging technological and scientific capabilities to design a livable and equitable future. For example, what if the think tanks and advisory councils developing the rules for implementing global AI infrastructure included artists? What blind spots might be mitigated? What value systems might be designed into the “game board?” How may we support this kind of work and acknowledge that the best cross-disciplinary collaborations come out of building long-term relationships and lines of trust?

Neither scientists nor artists hold all the answers. “The truth is that it’s really tricky because I don’t know what’s coming,” says Ingrid Kopp of Electric South. “I’ve been in conversations about the robot revolution and biohacking, and all this, so I have an inkling, but I definitely don’t know. I suppose the problem is, if you invest in a lot of grassroots artists and social justice movements, they are probably mostly not going to be thinking about what to do when the robots take our jobs. …So I guess the problem with only a Buckminster Fuller or Misfit Economy approach is they’re never going to be able to compete with all those higher systems things that are coming our way and probably quite quickly.”

Imagining

Work in an AI Integrated Future Panel @ 2018 Sundance Film Festval

Imagining

Work in an AI Integrated Future Panel @ 2018 Sundance Film FestvalBarry Threw of Gray Area Foundation describes the need for artists to engage in spaces of function. “My belief is that artists are uniquely suited to respond to quickly changing, psychological social environments. Art is vital to put into these contexts [science, policy, technology]; otherwise, I think you’re flying blind. The other side of it is important too. Usually in the art context, people don’t like to talk about things being functional. A lot of the art is in a transcendent space, like in museums and galleries. There is this idea that an artist has to be apart from society and protected in sort of a third space. But I think that there is a definite role for artists to have a functional place within technology innovation and development and politics. Their role in the process is vital. ”

Vassiliki Khonsari, co-founder of Ink Stories and maker of the video game 1979 Revolution observed a big shift in the appreciation of content makers and artists by other sectors of society. She shared that when her partner, Navid Khonsari, was invited to consult on President Obama’s Maple Valleywood Project in D.C., the White House brought together people from the private sector to talk with the Department of Justice and to brainstorm with other content creators about how to fight ISIS. “It’s so interesting. It’s like this strong tradition of not investing in art, and, all of a sudden, you see the purpose in creating content that moves beyond policy, which is the role of the artist. This critical gap was so profoundly in focus at this event.”

Sarah Wolozin, director of MIT OpenDocs Lab observed that “people want us at the table. They understand now that we’re in a visual world. I think more and more institutions are realizing how media can help further their mission in a way that wasn’t understood before. There’s a lot more crossover from Planned Parenthood to the UN [to the] The World Economic Forum… We all know we’re in a moment where our whole society is being shaken up, and so we need to re-define the practices and the processes and the best practices for how to live. ”

Of course, this recommendation to embed artists in centers of power needs a discerning approach. Interviewees advised selecting artists who can speak comfortably and persuasively with the business community, politicians, engineers, and technologists, while maintaining their artistic values. Interviewees also recommended that interdisciplinary programs establish rules of engagement and expectations to ensure reciprocal environments. However, the onus should not only be on the artists to “fit” into the spaces of power, Wendy Levy advocates for building capacity within these companies and organizations so they understand what it means “to have a filmmaker or a theatre maker or a poet at the table when the design of the new millennium is happening.”

Multimedia artists Lynette Wallworth and Skawennati warned against monopolizing artists’ time with strategic design conversations, where they are talking more than creating. It is important to have artists included, but not at the cost of making their art, which requires a very different headspace, time for reflection, inspiration, and play. Also, artists cannot feel used by the process; they must want to engage and be clear about the value proposition to their own work.

“When incorporating diversity of thinking into any discussion,” suggests Chris Hollenbeck, the Managing Director of Granite Ventures. “It’s super important to identify a problem to solve or be fairly specific about what are we trying to accomplish. Big open-ended questions and lots of diverse thinking may lead to brilliant epiphanies, but it often leads to not enough structure. Then you’ve got people talking past each other, because they don’t come from the same framework and there’s no gravity to pull them together to say, ‘Okay, we’re focused on this issue, this fairly specific problem.’ And maybe that’s just personal experience, but in talking to folks in the arts about technology, it often gets down to ‘technology is bad,’ and ‘nobody values art,’ and ‘these people don’t get it, and they’re self centered’…which I don’t think is necessarily true.”

So, for these kinds of programs to succeed, they must have clear missions, clear and compelling value propositions to all involved, and clear measures of achievable success. Also, the outcome may not be a high-impact art project or clear innovation in technology or social system design. It may be much more subtle, especially at first. Longitudinal observations and success measurements must be considered.

Here is a list of just a few institutions and think tanks working to figure out the future of emerging media and tech, which could be target partners for programs to embed or engage artists:

- Partnership on Artificial Intelligence to Benefit People and Society

- The Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at the University of Cambridge

- World Economic Forum Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution

- Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence

- Stanford University’s 100-year study on AI

- Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS)

- The VR/AR Association (The VRARA)

- Open AI

- UC Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible Artificial Intelligence

- World Intellectual Property Organization

- Augmented Reality for Enterprise Alliance (AREA)

- New Horizons: Blockchain x IoT Summit

- The Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Fund

Thoughtfully include the arts in spaces of power

Wallworth’s long-term engagement with the cultural director of the World Economic Forum (WEF), Nico Daswani, is a great testimony to the good that can come from breaking down silos in spaces of power. In the past, the Forum invited artists to present their work, almost as a reward to the attendees at the end of the day (i.e. evening concert by Yo-Yo Ma), but the artists were not invited into the conversations. Wallworth and Daswani modeled a different, more integrated way of including artists’ voices in the dialogue. Wallworth presented transformative works about climate change, indigenous land rights, nuclear test bans, and constraints on mining policies over a period of several years of WEF programming. This allowed the artwork to become a part of key conversations. Then Wallworth replicated that level of engagement at other global, policy forums and was named one of the top 100 most influential people in foreign policy by Foreign Policy magazine.

Her work in the context of WEF is captured in the article “Virtual reality virtuoso: why Australian artist Lynette Wallworth is making waves,” published in SMH.com, which recounts this scene:

In September 2014, in the Chinese city of Tianjin, several dozen of the world’s most powerful people — finance ministers, business leaders, economists and at least one Saudi oil baron — walked into a large inflatable dome, lay down on bean bags and stared at the ceiling. All were in Tianjin for “Summer Davos,” one of the annual gatherings of the World Economic Forum (WEF). In a break from back-to-back panel discussions, the audience had gathered to watch a short film,Coral: Rekindling Venus, by the Australian artist Lynette Wallworth. Merely getting them into the dome had been a struggle: most had to be convinced that watching a 22-minute nature documentary was a productive use of their time….“The film was about the oceans, about climate change, but there was no voiceover or expressed call to action,” says Nico Daswani, the WEF’s head of Arts and Culture, who was instrumental in bringing Coral to the forum. “Yet the feeling people came out with was, ‘This is so beautiful, I have to protect it.’ ” By the next day, word had spread. “The queue to see Coral was 40 minutes long,” Daswani says. “That’s the power of Lynette’s work.”

Claudia Peña suggested a complimentary approach to support or catalyze organizations to make the arts a core value, even when they work in a traditionally non-arts focused area of the economy. She noted that a national civil rights organization called Equal Justice Society positions themselves as a hybrid of the arts, law, and social science with the tagline: Equal Justice Society, transforming the nation’s consciousness on race through the law, social science, and the arts.

Build interdisciplinary community outside spaces of power

Interviewees such as Lance Weiler provided strategies affectionately referred to as the “Buckminster Fuller Approach” because they circumvent tech and business centers by investing in regionally diverse, community-based programs to catalyze innovation by providing space, tools, and learning.

Kopp reflects, “I really agree with those kinds of decentralizing ideas. How do we get into these spaces? How do we get artists into these spaces so we can have critical intervention in big spaces and small spaces? It doesn’t all have to be at the Microsoft and Facebooks [of the world]. We probably need to be in community spaces, too, because, otherwise, we can never go into making an impact in those scaled up-spaces. I think we need to be in both. You need a bottom-up approach, and a top-down approach. One of them is more about small interventions and seeding, and another is about things like policy, think tanks, and public algorithms.”

Investment parity

Another major area of recommendations offer to help break the silos, groupthink and knowledge ghettos between the arts, tech, science and policy involved establishing greater investment parity in creative sector professionals, companies and organizations. This month’s supplemental article outlines the ideas offered by interviewees about the need to provide public funding for emerging media and speculative arts; and to encourage creative entrepreneurship.

The Making a New Reality research project is authored by Kamal Sinclair with support from the Ford Foundation JustFilms program and supplemental support from the Sundance Institute. Learn more about the goals and methods of this research, who produced it, and the interviewees whose insights inform the analysis.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.