Part 4 in a series by Kamal Sinclair

Early in 2015, I had a conversation with a lovely man who leads the futurist department for one of the largest tech companies in the world. His team would imagine the future with the company’s pipeline technologies and build out offices and homes in the vision of these technologies. He showed me a short film about how they were imagining the future, and it felt exciting in terms of the technology capabilities, but a bit soulless. I asked if he had anyone from the arts and humanities on his team. He said “No, just engineers.” I asked, “How are you imagining the future without people from the arts and humanities?” He genuinely looked flummoxed and said, “Wow, that’s a blind spot.”

NASA’s Columbia Space Shuttle

(2003 Launch)

NASA’s Columbia Space Shuttle

(2003 Launch)We have plenty of precedents that suggest that blind spots can be dangerous. When I was in grad school, we were given a case study that identified the primary reason for the Columbia Space Shuttle tragedy: groupthink. NASA’s homogenous and top-down management structure caused them to have major blind spots, even willful ones that led to the explosion. How do you counter groupthink? Besides remaining open to criticism and training team members in group decision making, the two critical counters are to work with diverse groups of people and to include members outside the group in meetings and decision-making. Throughout the Making a New Reality interviews I heard artists, scientists, policy experts, entrepreneurs, and technologists lament the silos that isolate respective fields of knowledge in the design and imagination of our future.

Of course, this relates back to the previous articles on the need to diversify emerging media from an identity and regional perspective. Countering groupthink involves includes a diversity of identity backgrounds, as well as a diversity of fields of knowledge and discipline. See High Stakes of Limited Inclusion, Challenging the Innovator Stereotype, and The Radical Opportunity.

Accident investigators

reconstructed space shuttle Columbia from recovered debris. (Reuters/NASA)

Accident investigators

reconstructed space shuttle Columbia from recovered debris. (Reuters/NASA)Designing with blind spots

Robert Wong, the lead of Google’s Creative Lab, raised concerns about the marginalization of people from the arts and humanities in the tech sector. Others have raised concerns about the marginalization of technologists in the arts and humanities sectors, especially those in the gaming sector who are not considered “serious” contributors to society, even though they possess a high set of skills and a full working knowledge of social structure, tech and code, business, and the arts. The concern goes back to the notion that, if we do not have diverse kinds of people and skill sets contributing to the design of our future, we may fail to create systems that are human-centered and inclusive.

Multiple people said that they are also concerned that fundamentals of history and philosophy are missing from the knowledge base of tech leadership. Interviewees shared various anecdotes of conversations with leaders at major tech firms who did not have a fundamental understanding of the historical dynamics that shape current cultures. They fear that these blind spots could lead to unintended cultural and political disruptions, especially when considering powerful tools such as AI.

“I think [tech firms] need more artists and more critical engineering, meaning engineers who have history degrees, which is a thing that has basically vanished,” says Luke DuBois, artist, creative technologists and researcher at NYU’s Brooklyn Experimental Media Center. “So that’s a problem: It’s not even art that’s missing, it’s the broad stroke of liberal arts…That’s how they make those mistakes, where they roll out an image labeling system that labels African-American people as gorillas…Those are easily preventable f**k-ups that could be mitigated if people had a better breadth of education and understanding of the social impact of their research.”

Miles Perkins (VP of Communications at Jaunt) identified our education system as one major source for these silos of the arts and humanities, engineering, and business in the tech and media fields, saying., “We have taught a generation of students to value STEM over STEAM [which adds “Arts” to Science, Technology, Engineering and Math] in the last 25 years.” As a former employee of Lucasfilm’s Industrial Light & Magic and now an executive at a Silicon Valley VR startup, Perkins has seen major challenges in translating ideas across these silos. Britt Wray (artist, journalist, and biologist) similarly described this gap between the arts and sciences, adding that it is not only a lack of shared language that becomes a stumbling block, but a lack of respect for each others’ fields of expertise.

Luke DuBois agrees, “Part of it is the universities’ fault. For the last 15 years we’ve been STEMifying the sh** out of everything we do, so if you do computer science at Stanford, you get pipelined straight into Facebook or Google, but for that degree program, you don’t really have to take any humanities classes in depth. Because math — like pure math, and pure physics — count as liberal arts, because they’re not applied classes, they’re theory classes. So then you take, like, freshman English so you can write a five-paragraph essay, but you don’t have to really engage with or know anything about society.”

Fortunately, DuBois sees some attempts to change course, “We’re trying to fix this over at NYU now. We’re developing a core curriculum for engineering students to counteract that, so they all have to take an ethics class, and they all have to take a history and philosophy of science and technology class, so that they understand that this stuff doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Because you only know what you know, so it’s not their fault. It’s our fault for letting them get away with it.”

Nancy Schwartzman, an artist, technologist, and activist also called for breaking these silos through the education system. “If every new student at MIT and Caltech had to take a civics class about intersections of gender, ability, race and class oppression, and [if the class could] challenge students to harness the power of technology to address these problems and subvert these structures, we’d probably get more civic-minded technologists and art.”

Golan Levin, Associate Professor of Electronic Time-Based Art at Carnegie Mellon School of Art, was very generous with his analysis of the issue, “When our students go and try and learn programming over in computer science, first (as Leah Buechley has pointed out) those departments teach programming with certain kinds of assumptions. Those assumptions are that you are probably going to go to work in a cubicle at a big company like Microsoft. Therefore, they don’t teach you to work in ways that are improvisational. They teach you to work in ways that are planned. But artists like to work improvisationally. In computer science, you’re just not going to learn to work improvisationally. Instead, it’s more about computing a plan or satisfying a task that’s been given to you by a manager.. Second, computer science education traditionally assumes that you learn from abstract principles: ‘Here’s the equation. Here’s an abstract description of how it works. Now you know the material. Now you take the test.’ Artists don’t learn that way. They learn from making concrete examples, not from abstract principles. So, for artists, learning is often much more tinkering-driven, curiosity-driven, creativity-driven, and actually, hands-on with code — where you make stuff to figure out what’s makeable.”

To tackle this issue, all students studying game design at Carnegie Mellon are required to study improv. According to Drew Davidson, professor at Carnegie Mellon, improv teaches students to get over ego and focus on the scene and story, as well as how to work on a team that prioritizes the improv principle of “Yes, and…” rather than starting from “no.” This simple change in attitude, key to improvisational theatre, drastically impacts the tech field. VR maker Paisley Smith agrees with Levin, that Davidson’s approach is effective at expanding the critical thinking computer scientists and designers. She said she often reflects on a conversation she had with Davidson and has drawn of it as she developed her own work style at the intersection of art, tech and film.

Levin states, “The third issue, and this is more of a cultural thing, you go into a computer science department and there’s a strong bias towards making things which are utilitarian rather than expressive,” He explains: “Your job is to make this vending machine or this banking software, but an artist says, ‘Well, this doesn’t really speak to me.’ [Take] someone like Lauren McCarthy, who is doing incredibly important work in, not only creating tools but in providing documentation that gives artists a leg up in learning stuff and which has diversity built in as a value. Lauren’s an ideal example. You have someone who’s trying to make a programming environment for new learners, for people who are young and from different backgrounds, who are not necessarily going into this because they want to get a job with Google, but because they realize that code is a 21st century artistic medium that they want to use. There’s a really important opportunity to support the open-source arts engineering tool kits, and foundations could be doing that, but it’s a challenging thing to explain to [foundations], I think.”

Hyper-capitalism and short-termism

Marisa Jahn and other interviewees describe a time in the last century where STEAM was held in high value at places such as MIT and Bell Labs, which were creating intersectionality between these fields. They admit that there are programs for artists in tech companies, but many of them are “tinsel” and not rigorous. There was a sense of lament among these interviewees that the value systems of exponential economic growth and hyper-capitalism, as described by Douglas Rushkoff in his book Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, have encroached on the time, space, and resources for this kind of cross-pollination of ideas. Often driven by short-term gains, the free market has failed to account for long-term profits, impacts on culture and quality of life that breaking these silos can generate.

As Dayna Evans reports at NYMag.com, “When Mark Zuckerberg announced the purchase of Oculus VR for $2 billion in 2014, the first thing he said he intended to do with it is make better games. The second was enhancing the experience of ‘enjoying a courtside seat at a game.’ ” Although Zuckerberg’s vision of the utility of virtual reality for gaming and sports is valuable as a way of better serving the audiences for gaming and sports, some argue that it illustrates a narrow vision of the medium that a cross-pollination of ideas from people of different backgrounds could help to broaden.

“The technology is there to service the art, not the other way around,”suggests Maureen Fan the CEO Baobab Studios and an animation artist. She explained that the myth still persists that investing in higher artistic values and more rigorous stories for mass media products (for example, casual games) will limit, if not dissolve, profit margins. The Harvard Business Review published a case study on the development and success factors of Pixar and found that making heightened story the primary brand value and technological excellence a secondary core value was the key to the studio’s exponential economic success. Some argue the VR industry suffered from a tech-first mentality in 2016, when the industry pushed hardware to launch ahead of an abundance of meaningful or cohesive content.

Eugene Chung, former head of Oculus film department and current CEO of Penrose Studios, shared that is was very difficult to get the company to invest in storytelling experiences in the beginning. Of course, there are valid arguments that sometimes artists are too attached to their creations and fail to make the hard business and engineering decisions that would enable them to reach beyond the niche, indie audiences. In recent years, Oculus has more deeply invested in non-gaming and non-sports experiences, stories, and communication functions. Due to the efforts of a host of advocates, the industry quickly course-corrected and invested more heavily in content in 2017, and now high quality content is being acquired out of festivals like Sundance Institute’s New Frontier at seven figures. Could this blind spot been avoided if artists had a greater locus of power in the beginning?

It’s hard to break silos

Some interviewees talked about the challenges of having people with deep knowledge of code and technology in conversation with people who just understand the end-user experience, but have creative ideas about how to make better designs. This can be difficult for both sides of the dialogue.

Tracy Fullerton, Director of the Game Innovation Lab at USC, explains that much of the siloed culture comes from day-to-day interactions: “There’s this kind of nerd macho, coding really long hours. There’s this way that we think of ourselves, and it is not friendly. It’s not inclusive it tends to not invite others into its sphere. So, even if you go in as a freshman to study computer science, you are on a daily basis going to be faced with this sense that you’re not invited.”

Yelena Rachitsky, Executive Producer of Experiences at Oculus, discussed her experience at the crossroads of storytelling and technology, “I come from the art world, and now I’m in a place that is a mixture of tech, at a company that’s majorly engineering focused [Facebook] and at Oculus, which has its foundation in the gaming space. I think part of the gap between the arts and tech is just that people come in from what they know and they tend to stay in that community. It’s just how you learn to think. It’s how you learn to value things, and so now that there’s this convergence, we’re having to re-open our minds to realize, ‘Oh, maybe this works better a different way.’ And that is not an easy thing to do. It’s also not an easy thing for me to do. I find myself having a hard time getting into the gaming mindset or the engineering mindset, coming from the film world. I’m used to it being very hierarchical, with the director first. In the tech world, it’s much more hierarchical with engineering first. And before I was in a world where the tech people just did what the creative people asked them to do. And now I’m having to realize that’s also a biased way to think, because the tech is just as important as the creative, because they’re the ones who are actually making it all possible.”

Wray, journalist and former scientist, explains a similar dynamic in hard sciences: “It feels like artist/scientist collaborations are still a marginal practice. Artists get invited into scientific spaces rarely, compared to those with the hard tech and hard engineering skills, because they’re perceived as less valuable. The artist or storyteller comes in and gets to benefit by learning about the atmosphere, the environment, the materials, and tools that all these scientists are using. They get to make captivating content that attaches their imagination to what the scientists are doing, but generally the scientists are sitting there thinking, ‘What do I get from this? I’m sharing my lab bench with you, but how do I necessarily incorporate what you have to show me into my work?’ This is an ongoing question in synthetic biology. We need to get clearer about what the benefits are to scientists and how it could be more collaborative, rather than like a one-way partnership.”

Wray explained that one of her biggest concerns is that small scientific communities such as synthetic biologists are making huge decisions that could affect the fundamental design of human bodies in the next twenty years without being in discourse with other fields of knowledge, such as the arts and humanities. “It’s too much responsibility.”

Lost value

One executive from a major tech company developing AR capability described his excitement for the medium becoming a computing platform at a SXSW dinner in 2016. “Won’t it be great when you can do your emails, wearing an AR device, like this [held up his hands and air typed, as if on a standard keyboard].” He was quickly followed by an artist at the table, with a dance background, who said to a shocked audience, “If I no longer have to be bound by a keyboard, why in the world would I want to air type on a hologram version of one? I’d rather do this [she performed a series of lyrical gestures].” This is an example of how different viewpoints might spark a wider scope of approaches to new technology, which is lost in a siloed environment.

Dan Novy, MIT Media Lab engineer, is a strong advocate of bridging this gap, especially in media innovation. Not only should artists and technologists collaborate more intimately to optimize the technology, he thinks they should do so earlier in the process. He notes the current process typically does not involve media makers until the product comes to market, then the artist is creatively constrained by the limitations of the technology. They either play inside the lines of the tech or hack the tech to get results the original product does not provide (i.e., James George & Jonathan Minard’s hack of Kinect technology to create computer vision cameras in CLOUDS). The engineers see the hack and iterate the product to better match the artist’s needs. Novy says this cycle would be more efficient if the artists were collaborating with the engineers from the beginning of concept.

McCarthy explains that, “One problem is that it’s really hard to get any support for building tools, because it is not the central thing. It’s an alternative model, or it’s just not as flashy to be building the tools that are underlying the final installation. But, I think that’s where you need the most diversity, because a tool is not neutral. It reflects the ideas of its creators. If we have one homogenous group making all the tools that we make our art with, our stories will all be shaped by what’s possible in the tool. So, I guess that’s why I focus my attention there.” McCarthy is an artist and programmer, and the creator of the tool p5.js, a javascript library which makes coding accessible to creators.

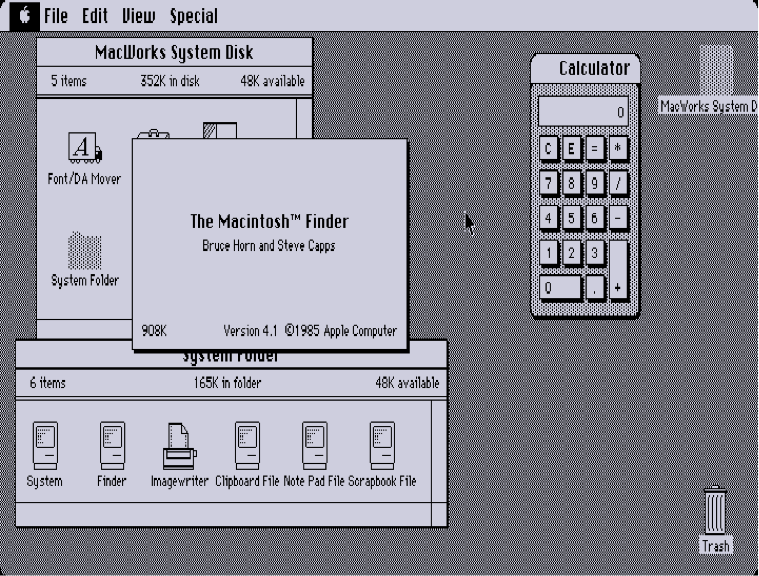

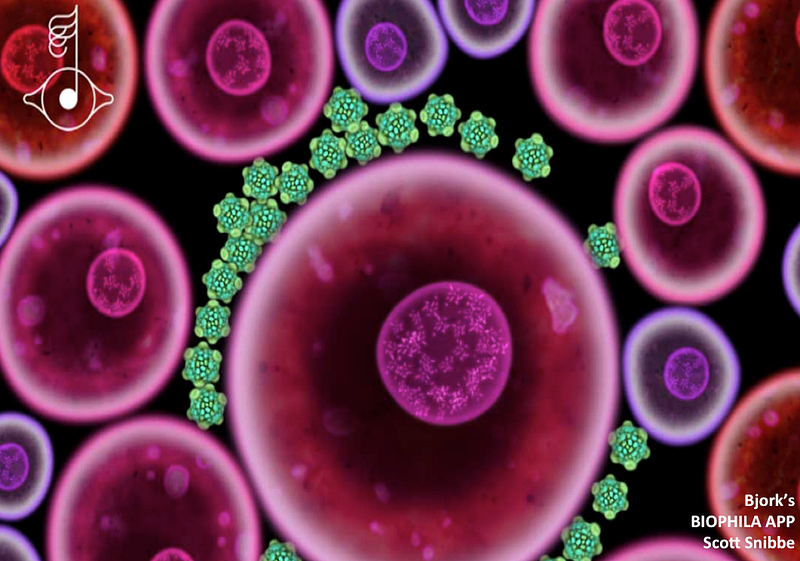

Scott Snibbe, an interactive artist and creative technologist, describes the first time he used the Apple II computer, back in the beginning of personal computing. As an artist, he saw the blinking green cursor on the jet-black screen as pure possibility, an infinite and multi-dimensional creative canvas. So, when Microsoft issued its operating system and put the entire universe of possibilities that existed on the black screen into a desktop framework, he was devastated. The immense creativity of this medium was now under the mental constraints of work/office productivity. He had to circumvent this framework in his practice for decades, before Apple gave him a new infinite and multi-dimensional canvas in the iPad tablet. With that new tool, he has created some of the most astounding UX/UI designed works in the field, such as Bjork’s Biophilia concept album.

These gaps between scientists, technologist, engineers, the artists and humanities experts are similar to identity divisions among people in emerging media, in that once you get past the friction, you realize the people on either side are more alike than not. In this instance, both the arts and the sciences are charged with investigating what it means to be human and how we might improve our state of being. They both explore truth and require imagination. They help us understand our minds and bodies. They hold up a mirror to humanity. They open our imaginations to what could be.

Groupthink in emerging media

Interviewees identified several areas of emerging tech and media that seem to suffer from groupthink, due to a lack of rigorous diversity and a failure of rich cross-field discourse. This month’s supplemental articles aim to share some of those concerns:

- Biased Algorithms and the False Sense of Democratization

- Consolidated Media Landscape

- Navigating Disruption

The Making a New Reality research project is authored by Kamal Sinclair with support from the Ford Foundation JustFilms program and supplemental support from the Sundance Institute. Learn more about the goals and methods of this research, who produced it, and the interviewees whose insights inform the analysis.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.