The Artist-Engineer in VR

In conversation with Xin Liu and Qinya Guo

This interview was conducted by Andrea Kim and Samuel Mendez, research assistants at MIT’s Open Documentary Lab. The conversation has been edited and condensed for space and clarity.

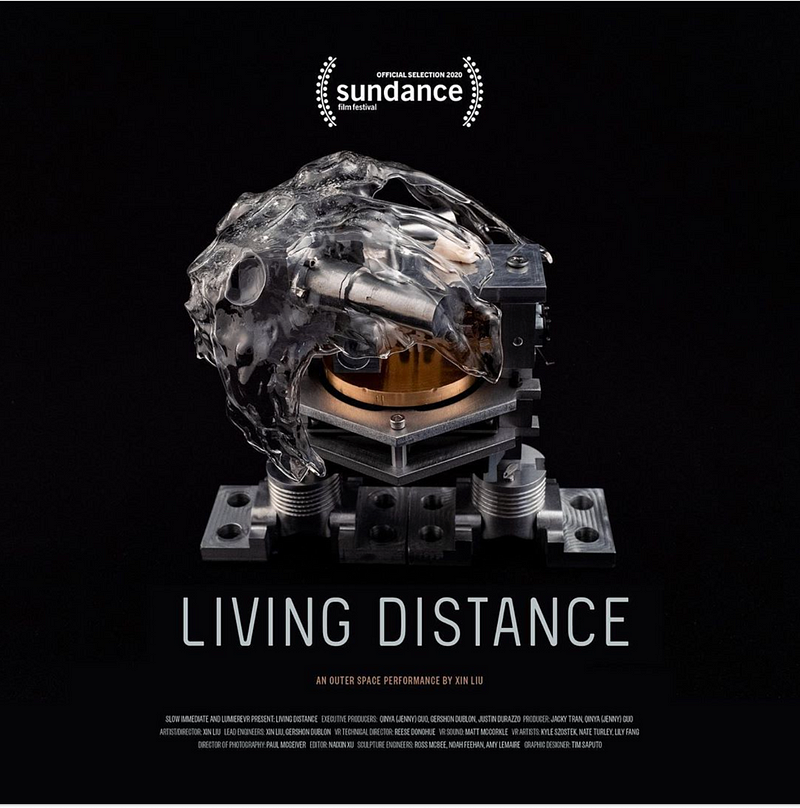

At Sundance New Frontiers 2020, Xin Liu and Qinya (Jenny) Guo debuted Living Distance, a VR piece about the journey of Liu’s wisdom tooth, which was launched into space on Flight NS-11 in a crystalline robotic sculpture.

Liu, the lead artist and director of Living Distance, has created works ranging from performances and installations to scientific experiments and academic papers. She is currently the Arts Curator in Space Exploration Initiative at the MIT Media Lab. Guo, the executive producer, is an award-winning cross-border creative producer, XR arts collector and tech entrepreneur at LumeireVR. In this interview, Kim and Mendez sit down with the two of them to discuss their approach to blending high technology with human themes to tell stories in VR.

Kim: What was the motivation between using different sorts of mediums, and what does the VR bring out that the others don’t?

Liu: Essentially, this work is an outer space performance. Everything else is the way to access that piece. They’re not translating in a literal way. They are providing access for people to be connected to it, because no one actually went to space.

Guo: I think because of [Xin’s] background in contemporary art, her piece is very conceptual. It’s like a grand gesture. When we first started to talk about VR we were thinking more about how to make people have that kind of personal attachment because if you do VR right you can bring more senses and memories and feelings out of the audience compared to watching a video or seeing a sculpture. The VR experience is more embodied, done with sound and haptics to try and have that sense that something so far away can be so close to us.

Liu: This piece is really like a dream from the tooth’s perspective. No matter if it’s a dream when you’re still in the mouth or the dream of infinite darkness, they’re similar, and virtuality feels like the only medium that makes sense for that interpretation.

Kim: So is the tooth not supposed to be a symbol that’s connected to the human itself?

Liu: It is one’s self, but it is also the realization that part of yourself is going to leave — and then the detachment that comes out of this work. I was talking to many people earlier [who experienced the work] feeling like a voyager leaving the earth, a person leaving their hometown — a tooth leaving you is kind of the same thing. When it left, [the tooth] became its own and that realization and recognition is a lot of what this piece is about..

Kim: Can you speak more to the decision to make the user experience more passive?

Liu: You’re a tooth. So you’re not supposed to be [active]. I was more interested in the possibility of something leaking out and you weren’t sure whether you could control it. And that is weird. The subjectivity and outside world get blurry. So that’s why for the piece, we do make you very passive, but at the same time you are moving, because the chair is moving.

The power of the body can make you feel like you are taking some action but not necessarily in a hundred percent conscious way. And that plays between a subconscious and dreamlike experience and the visual and the sound. The sound is very complicated, the way we designed it. It’s all ambisonic. So when you move your head the sound actually changes very subtly.

Guo: In VR, lots of times, you have to establish that kind of connection between the subject and the audience who entered. In the beginning, it is not really synchronized. People are repelled by the medium right away. That’s why there are so many narrative VR films that are not successful even if those story’s good. Many times in VR, a linear time-based storyline doesn’t work out too well. But more dreamlike states actually provide more of that kind of curiosity and exploration to the space and the sound and visuals.

Xin Liu (left) and Jenny Guo

(right)

Xin Liu (left) and Jenny Guo

(right)Mendez: I think there’s a really nice sense of detachment and isolation. Even though you’re going to all these crazy wide open places there is a real sense of being locked in. Do these themes relate to some of your past work?

Liu: Within my own work I definitely question a lot about how we understand what we feel and what identity and subjectivity are, where emotions come from and go. I think that sometimes there are feelings we kind of ignore because we want an answer right away.

In Chinese, I would say, “distance creates beauty.” Actually, this name started with this song by Grandaddy, “Everything Beautiful is Far Away.” I want to tap that feeling in his piece. And I think that feeling is universal, but somehow there’s no word for it. It’s not like happiness or sadness. It’s somewhere in between. It’s almost melancholic but not sad. And that’s the kind of aesthetic of this piece.

Mendez: I really like the capturing of that kind of double-edged sword of, “I want to go off and do and see all these things,” but then that also means I’m leaving all these other things.

Liu: And I think that works for both of us [Jenny and I] cause we’re far from home and drifting for a while. Jenny came to the U.S. in high school and I [have been here] for six years now. I believe lots of people in a modern society share the same feeling.

Mendez: I’m curious about your process of combining this very high technology with this simple organic thing like a tooth.

Guo: I think VR and other technology are all tools. I always encourage creators to focus less on, “I’m going to use EEG, I’m gonna use this,” because at the end of the day it will be very gimmicky for this piece.

Mendez: What are some of the things that you learned in your previous performances and exhibits that benefited this project?

Liu: I am working from installation and visual art. So, it’s very easy to translate even though I never had a film background and VR is not a good frame. It’s a space, and I’m very familiar with that.

As an artist, I think what I have learned most is that you really need to trust the audience. Because lots of times, as artists and creators, we think people don’t understand and we start adding things to explain, to simplify, to compromise. But for VR particularly, I think it’s lucky because you kind of lock someone in a world. It’s actually easier than visual arts to be very honest. Because when I have a picture, when I have a video piece, a sculpture, they can come and go. In VR, most of them will stay unless it’s really bad.

Kim: Could you speak a bit more about how audiences perceived the work and how people perceive the medium?

Liu: You need the language and people understanding that it can even be considered artwork. I feel like in a way it [requires] patience from both sides. As cultural producers, we need to [be patient with] the audience for them to get more exposed to the kind of things we’re doing. I think audiences also need a lot more patience nowadays because we are all on Instagram. We want to understand what’s going on immediately.

Guo: Also from a producer’s point of view, thinking about distribution for this field, we’re able to come to festivals and try to make people actually understand that art pieces could be created in different ways. So, for distribution, my plan is to take more of a festival route, which usually contemporary artists don’t choose. But we want this piece to be consumed by a more general public. Otherwise, you’d just sit in the galleries with industry people from the art world.

Kim: One last question. How would you want to support artist-engineers?

Liu: I believe you need to learn art and engineering separately and then let them grow together naturally. I do not 100% trust the idea of doing both at the same time, for example, from undergrad. I think they’re almost like two different languages that you learn and then, in the end, they somehow work together.

But at the same time, I think art-making is still art-making, no matter if it’s writing or painting or dancing or singing. Your desire is to make something and be brave enough to show it to the world. I think that feeling and emotional desire is always the same no matter what medium you use. And technology is really just one potential medium.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.