A conversation with interactive storyteller Illya Szilak

Queerskins: Ark collage, courtesy of Intel Studios and

Cloudred

Queerskins: Ark collage, courtesy of Intel Studios and

CloudredIllya Szilak is a physician and an interactive storyteller who works as a part-time physician at the Rikers Island Correctional Facility in New York City. Her work there informs her work as a writer and virtual world builder. I spoke with her in mid-June via Zoom.

In part, these worlds consist of using open-source media and collaborations forged via the internet to create multimedia novels such as Reconstructing Mayakovsky: A Novel of the Future. Inspired by Vladimir Mayakovsky, a Russian Futurist poet who killed himself in 1930 at the age of thirty-six, the book imagines a dystopia where uncertainty and tragedy have finally been eliminated through technology.

Since 2013, Szilak has been crafting a multi-part experience: Queerskins: A Novel features text, audio, and video; Queerskins: A Love Story is the VR piece based on it. The multimedia narrative follows Sebastian, a young gay physician estranged from his rural Catholic Missouri family who died of AIDS in 1990. The novel begins with Mary-Helen Adler’s discovery of her son’s diaries, written by Szilak. By reading these intimate texts and handling modeled personal objects, users are able to piece together Sebastian’s life. In addition, audio files of five other characters, including Sebastian’s mother, form a virtual Greek chorus commenting on his character and actions.

Szilak’s long-time creative partner, Cyril Tsiboulski, is the co-founder and creative director at cloudred, an interactive design studio. Much of their work together is influenced by non-VR art, and persistently asks visitors to think about what is lost and gained when touch and interaction become computer-mediated. This summer and fall, the two are devoted to creating Queerskins: Ark, the second of four planned chapters of Sebastian’s story.

IMMERSE: We’re living now in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, quarantining ourselves, and becoming more aware of the ways in which we can or cannot use our sense of touch. How are you navigating things at this moment in time?

ILLYA SZILAK: What’s so remarkable about this time is that while we’ve pivoted towards the digital, we’re also experiencing how impoverished that state actually is. I think we need to really consider what that means for us as human beings going into the future. There’s a real lack of recognition as to where this technology is taking us in terms of what we humans, as a species, need. What coronavirus has shown us, clearly, is that we need touch; we need to be together.

As a physician and as a storyteller, I’m embodied — as is everyone else — but my relationship to bodies through my work is quite intense and dramatic on a daily basis. I can’t move into a mode of transcendent abstraction — certainly not working in a jail!

The art of medicine is a storytelling art. Early on, in my work with HIV patients I found that sometimes the easier part of the job was figuring out what kind of drug combination to put someone on. The more complex issues were in developing trust with a patient. We now put everyone on HIV medications when they get tested, no matter what their immune system looks like. How do you convince someone who feels well to be on medication that will also probably give him side effects? A rapport needs to be established so that you can figure out where someone’s coming from and retell his story in a way that he can realize the therapeutic possibilities from that. That’s certainly not the same for everyone and it’s also not something I learned to do in medical school. That art of being able to connect with people through dialogue and laying-on of hands and then telling that story back is part of how I work.

When you and Cyril started creating these virtual worlds for Queerskins, you wanted visitors to be actively involved. Can you speak to the transformation from your “flat” writing process to a spatial one?

Even in the early days, when we were making Mayakovsky, there was a lot of outside information crowded into it. It was really important for me to take on this concept of an “archive” and turn it on its head.

An archive connotes a collection for all time, for eternity, and it generally doesn’t change over time, especially when someone has already passed away. But in this archive, it all linked out into the internet universe. The beautiful thing about it is that as time has passed, those links have continued to break and what’s left is a collection of 404 errors. That archive depended on other people in the community to support it.

The art of medicine is a storytelling art.

In a procedural way, we wanted to speak to the nature of human knowledge and how things are not, in fact, set in time; they move through time. So, that archive has slowly degenerated.

For me, that’s a hopeful thing. Other writers are always appalled and wonder how I can stand that happening to this thing that I spent so much time creating. But I feel that relying on other people and sources of information to sustain it is really heartening.

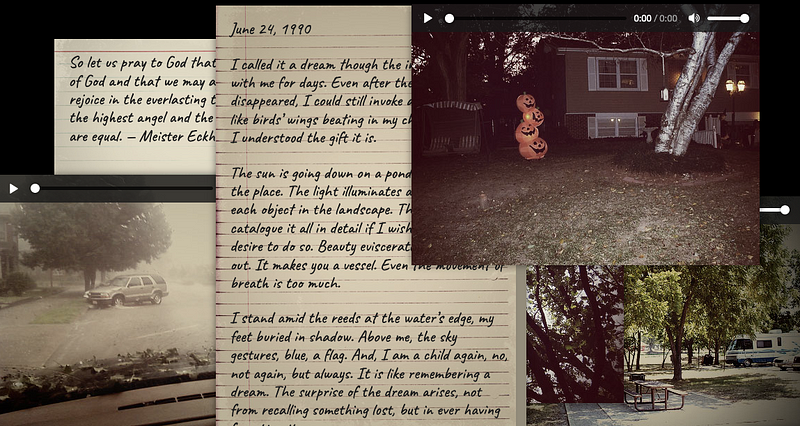

The pivot to spatial with Queerskins was a process. The online version is 2D,but we brought in community stories using Flickr Creative Commons photographs. What interested me about those photographs, especially the ones from Missouri, were those where I asked myself: Why did they take that picture and then share it as something people can see and use? They’re just totally mundane pictures. But I didn’t want artistry; I wanted documentation of everyday life. Bringing those in as backdrops against this very dramatic diary of Sebastian’s was a way of incorporating others’ stories from the get go.

Initially, in a very straightforward method, I began to adopt this way of writing stories from Sebastian’s diary from 2D to virtual. I was consulting with Oscar Raby, an amazing VR creator in Australia. After a full year, what became clear is that I couldn’t just take what existed in 2D and move it into a spatial realm. The experience of Queerskins is not possible in the online novel.

Now, I understand better the relationship between space and embodied cognition, but all I knew then was that I needed to build those spaces where people could insert their own stories. It’s a very slow piece, actually; it’s geared for contemplation. The discovery is really through how you respond to the objects in the environment.

The dialogue that is happening in front of you is in close proximity and you listen to a very intimate conversation. If you were to read it in a book, I’m not sure what you’d get out of it. It might read as something experimental because the rhythms of the language are more like poetry than prose. But in a spatial medium, there’s so much more you can do with that, so it works. Because the spectator can become a storyteller on an imaginative level, that’s where those blanks get filled in. The objects themselves are related thematically to the diary and that’s where the complex process of world-building takes place.

Your relationship to, say, this Hulk mask from the 1970s is not from the character, because Sebastian doesn’t exist except in these elements. We knew that the spectator would think back to his or her days as a kid dressing up for Halloween. This kind of thing doesn’t happen on a conscious level necessarily but it contributes to the emotional response to that object.

But what was also really important was that the spectator didn’t become the main character. There was no way in hell I was going to make you pretend to be a dead gay man. I mean, ethically, that’s so horrifying [laughter].

As we move into the second episode, Queerskins: Ark, that concept of interpretation and participation becomes literally about your own movement in space and how you decide to position yourself relative to Sebastian and his lover.

Sound is a spatial medium and it’s also the entry point of emotional response. Personally, I find sound to be much more capable of that feeling of transcendence than anything visual. What did you and Cyril discover as you were composing the soundscapes?

Again, going back to Reconstructing Mayakovsky, I can give you a small example.The experience is divided into mechanisms, different modes of getting into the story. One of them is a soundscape.

We didn’t have any money in 2008 so we used all Open Source code. The chapter numbers were just floating in space and if you hovered over one of them, you would get a piece of sound. Essentially, it was a thought puzzle. The curation of all these sounds was so much fun for me, finding selects that would relate somehow to the chapter, but not in a linear way. An example would be of a high school marching band playing the Spiderman theme song we found on an Internet archive.

With the online version of Queerskins and its diary text, you also have access to five characters who knew Sebastian, who talk about him in audio monologues. When I wrote those monologues, they were quite long, five to ten times as long as they appear. When I recorded them with actors and started putting the work together, I realized the power of the human voice going into your ear. It really didn’t matter how lyrical and beautiful the text was, because on a narrative level it couldn’t stand up to the sound of someone’s voice. So these were cut down to no more than a minute. This also circles back to wanting touch, because sound touches you. It literally penetrates your body.

Something that drives me nuts is what I call the Pixar aesthetic, this slick, easily consumable way of presenting narrative. It seems to be everywhere. Our computers can process that. But our computers don’t easily process sound files — they’re massive! In Queerskins: A Love Story, we decided that the 3D objects would have dramatically reduced pixel counts so that they wouldn’t break the experience.

Queerskins: a Love Story, courtesy of Illya Szilak and

Cyril Tsiboulski

Queerskins: a Love Story, courtesy of Illya Szilak and

Cyril TsiboulskiModeling the objects would have rendered them perfectly and that’s what I’m talking about when I mention this pervasive aesthetic. I really didn’t want that. I wanted objects taken from the time, such as that copy of Gray’s Anatomy from the 1970s that I found on eBay. Those frayed edges and imperfections were what I wanted in our experiences because it’s a connection to analogue space.

And in terms of sound, what I love about it in this case are the possibilities of polyphony, multiple voices talking simultaneously. Online, those voices and sounds are literally fragmented and so it takes on this symphonic aspect. Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s theories on heteroglossia — the truth that emerges out of multiple voices — has been extremely influential for me from the very beginning of this work.

You’re currently working with a designer on a piece of clothing one can wear to feel something physical in a virtual medium. Your installation for Queerskins: Ark will feature actual wearable “queer skins.”

I started to collaborate with Loise Braganza, who is based in Mumbai. In the installation, touch was going to be a huge part of Ark before Coronavirus hit. These queer skins are kind of like a second skin — a way for people to immediately confront their own embodied existence.

One of these pieces is this very worn satin pink teddy. Loise found this garment and sent me a video of one of her friends wearing it. But the woman was like a size minus zero. So you might be attracted to the garment and want to wear it but then you had to confront the fact that your body couldn’t fit into it. Perhaps it would force you to confront your gender identity, for that matter.

However, current circumstances are forcing us to pivot to some kind of photography series. There isn’t really a replacement for human-to-human touch but there can be other modes for exploring connection and intimacy.

The scenes are shot with 360 video and volumetric 3D video. In the 360 scenes with Sebastian’s mom, Mary-Helen, you’re really constricted. The 360 forces passivity — you can look around but you can’t do anything or move through the space. But then there’s this Peter Pan move where you kind of fly out a window straight into Mary-Helen’s imagination, and that’s where you gain agency to move around.

Sebastian and his lover are sitting on a blanket on a beach. They’re having a very intimate conversation. The sound supervisor is Kevin Bolen from Skywalker Sound, who also did the sound for Queerskins: A Love Story.

I wanted to make something where if you were standing too far away, you wouldn’t be able to hear what Sebastian and his lover were saying. They’re aestheticized so that they appear as figures from memory, not totally embodied. You need to get close to them in order to hear the words. Kevin was excited that someone finally wanted to play with that kind of sound gradient.

In the dance scene, we wanted to create the connection between your body and their bodies. We did a lot of experimentation. I don’t want to give everything away, but an example would be that if you were to open your arms wide, your body gets reflected as a light upon the dancing couple — you literally illuminate them. It’s a beautiful effect.

The title of this new chapter, Queerskins: Ark, is such an evocative one. It could be an acronym or a reference to Noah’s ark. It’s also evocative of the dance of the two men as their bodies coalesce and then separate. When it’s spelled with a “c,” we can think about the arc of a story or the arc of a saga.

I love that reference to Noah’s ark and the possibility of a new existence. Of course, there was not a gay couple on that vessel — that was not part of the Biblical story! In the Bible story, God promises that he’ll never do that to the world again by creating a rainbow — which is also an arc and a sign of gay pride.

As well, that conflation of ark and arc is definitely purposeful and it’s about where the visitor is coming from. We wanted a word that would help to bring people’s own experiences into the story, even into the title itself. That complexity enables multiple points of entry into the experience.

What I wanted as well were those two words together: queer skins. So people at film festivals would say: I’m going to go see Queerskins. Maybe there’s a grain of discomfort when someone says those two words together. But what happened quite a lot is that word was like a beacon. Every queer of every stripe came and saw our experience.

When we were at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, this kid — anyone under twenty-five is a kid to me — spent an hour and a half in the installation. We got a chance to chat and he told me it did feel like home, that it was okay to be exactly who he was, that he felt that this was made for him. So that attention to detail is in absolutely everything we build and how we name everything.

My relationship to language starts there and it’s so odd to me that the most pushback I’ve received for this work is from other writers. But the world is evolving and text is evolving too. I’m writing for the generations to come.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.