ENCRYPTED

MESSAGE IN DCT: A Vernacular of File Formats, JPEG, 2010. Rosa Menkman, CC BY https://flickr.com/photos/r00s/24846351943

ENCRYPTED

MESSAGE IN DCT: A Vernacular of File Formats, JPEG, 2010. Rosa Menkman, CC BY https://flickr.com/photos/r00s/24846351943

On Preserving Non-Fiction Interactives

There is a corner of the web that tells us stories — non-fiction stories, specifically—which let us in on each other’s realities, ask us to slow down and contemplate. These works have many names: immersives, interactive documentaries (aka i-docs) or transmedia productions. Their makers draw from a large tool set: from playful game interactions, to networked, participatory, or data storytelling. Regardless of their underlying media or methods, however, these works share a common challenge: The average life span of a web page is 100 days.

Due to changes in ownership, or platforms switched off, online works of any kind become obsolete at an ever increasing pace. Browser versions bring updates at neck-breaking speeds. Services disappear in the blink of an eye. APIs change their tune before you can type the words “Twitter feed.” This urges us to ask the question of how to preserve this unique, undefinable selection of storytelling feats.

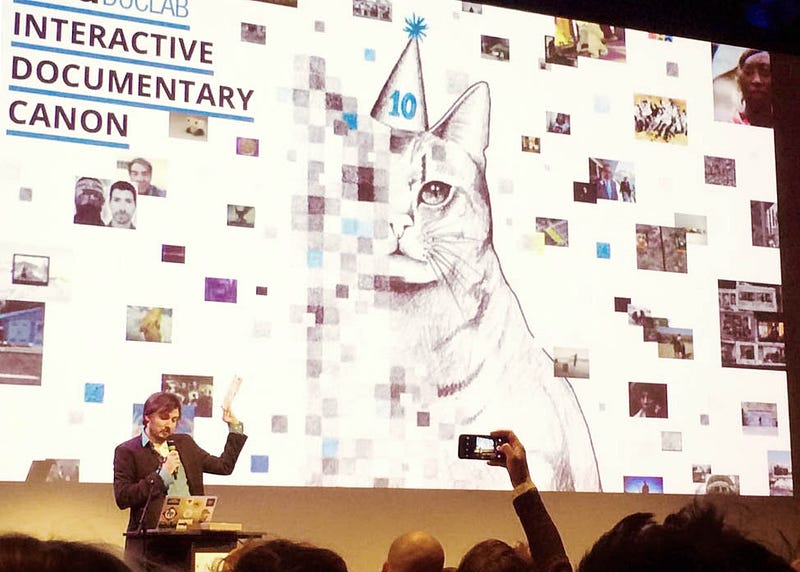

To celebrate ten years of undefined non-fiction storytelling and art at its anniversary edition in 2016, IDFA DocLab presented a selection of 95 works in “canonical” form. Such lists of key works allow us to clarify the status of both recent and early proponents of the interactive documentary.

IDFA

Doclab’s Caspar Sonnen presenting the Interactive Documentary Canon booklet.

IDFA

Doclab’s Caspar Sonnen presenting the Interactive Documentary Canon booklet.

What Does it Mean to Preserve Something?

When it comes to surviving the sands of time, there are few lucky accidents. History has left us some cultural artifacts despite, or even thanks to, a combination of lucky neglect and ideal atmospheric conditions. Think of frescoes excavated millennia after their abandonment, or terracotta armies uncovered thanks the utmost secrecy they were hidden with. But most, especially more recent examples, have found their way to our day and age through careful copying, tracking, and tending.

The time frame that allows us to preserve the digital record appears to shorten. Artifacts that aren’t cared for have a limited time span. With digital works, the sooner this tending can start, the more likely it is for experiences to be preserved for future generations. Producers of works that rely on embedded, ingested, updated, and outdated data streams need to be thinking about preservation from the start.

How? Document what was there before definitely turning off your site or app. Spend precious resources on making a work that was supposedly ready to be left behind whole again—or put a plan in place that foresees future changes in the work’s environment.

Digital Archiving: Where the Work is Never Over

The web has a history, large swaths of which have already been erased from the record. The Internet Archive began its Wayback Machine operations in 2001, a decade after the first browser came to life. National institutions, such as the Library of Congress, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and the UK’s National Archives (both France and the UK have legal deposit laws for web content) have all set up large-scale web scraping projects: approaching websites with crawlers that browse and copy what’s on their pages.

This type of front-end approach has its advantages: it can be operated at a large scale and is thus cost-effective, a bonus for cash-strapped public institutions. It is estimated that the Internet Archive, which provides the global public an incredible service with close to no public funds, is gathering some 2.5PB each year. Yet that’s not nearly enough. Preservationists estimate that not even 50% of world wide web content is subject to this type of hunting and gathering by archival organizations.

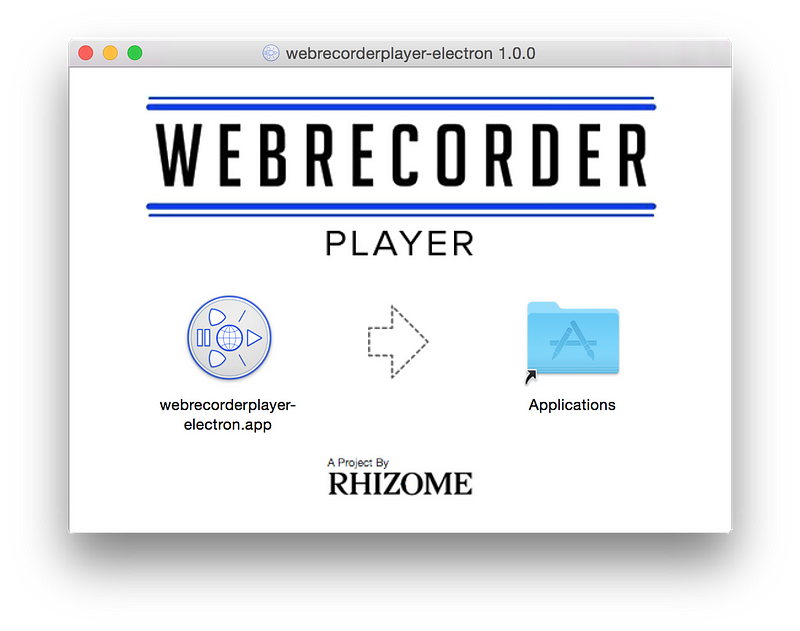

The dynamic, interactive web applications that make up our canon constitute the height of challenges for automated front-end crawling: user interaction, creating a vast amount of possible experiences, dependency on specific frameworks, externally hosted content. The New York-based organization Rhizome, well-acquainted with the challenges of media art works, developed its Webrecorder to overcome some of those limitations. Rhizone’s tool “records” the experience of browsing through a website, saving every applet that is called up — closely keeping the experience of one site visit, or multiple, depending on the amount of time one has to click through.

Rhizome’s

Webrecorder creates high-fidelity, interactive recordings of any web site you browse.

Rhizome’s

Webrecorder creates high-fidelity, interactive recordings of any web site you browse.

Fun and Games

Interactive documentary producers face not only the challenges of web preservation, but those facing game creators.

Games are at the cusp of technological innovation and prone to rapid release cycles. There is not one game experience: every player goes through the environment at his or her own pace, while the environment allows for countless interactions and storylines. Often, the game’s community is an integral part of the game’s experience. Without it, playing that game becomes a lonely sit-down in a digital desert.

Archiving games therefore comes with particular challenges. Solutions can mean not just emulating the operating environment or withdrawing the core code from obsolete carriers such as tapes and disks, but also documenting the way current generations interact with that game’s environment. This can happen in an organized fashion, such as what the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision is doing with the Game On! project. It can also be seen in the practice of gamers documenting their own game play on intensely popular YouTube channels.

For interactive producers, capturing the interplay between project and user may well also be part of their preservation approach.

Lessons from Media Art

Net artists have paved the way in reconstructing very specific machineries as they’ve struggled with how to overcome dying technologies and frameworks. Tool sets like the Variable Media Questionnaire allow an artist to indicate the exact changes to the work that they would or would not allow. As an example of this approach, see web artist Rafael Rozendaal on YouTube as he sat down with LIMA’s conservators for an extended session, explaining what elements of his works should or should not be reconstructed.

Digital artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer compiled a fantastic list for digital artists about how they can approach and develop their own preservation approach in a digital artists’ studio context. He discusses “versioning” artworks by means of using version control and making contracts with collectors about the extent to which support is included in their acquisition.

Interactive documentary’s context differs and overlaps with all of the above. These are funky, non-conforming animals in the online publishing world — works that depend on, forge forward with and heavily abuse those aspects of the dynamic web that crawler technology provides limited solutions for.

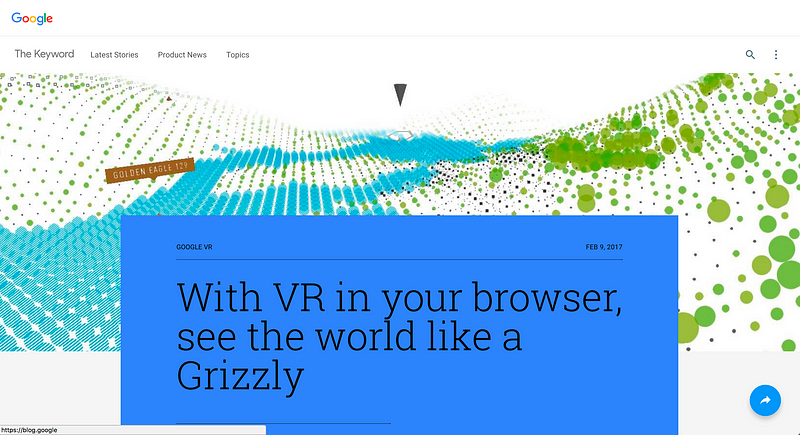

The NFB’s

Bear 71, first released in 2012, recreated in WebVR in 2017

The NFB’s

Bear 71, first released in 2012, recreated in WebVR in 2017Start Early, Start Now

As former head of the British Library’s web archiving program Helen Hockx-Yu described, projects like Antony Gormley’s One and Other, which she helped manually preserve back in 2010, require a vast amount of human care and attention. The trick is to find a way to preserve dynamic web creations without having to resort to manual methods.

It’s perhaps not wise to wait for all the answers. Andrea Byrne, the former digital preservation officer at Archives New Zealand, has outlined goals for 2017 to help enable producers to take on the responsibility to record and document their experiences themselves. This makes sense, because they know best what frameworks, standards and hacks their storyline was built with in the first place.

For example, one of the works from the canon, NFB’s Bear 71, was a mere 5 years old when Flash technology died down. With VR trying to find its way to the consumer market over the course of 2016 the technology was revamped as a webVR experience with support from the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, IDFA, and Google.

With software, net art, or any digital work, the creation process must be accompanied by some accounting for how the machinery can be made future-proof. (Unless, that is, the work is designed to live in the moment only, and never to be admired again.) “Preserving” — a term that refers to a host of actions to make objects future-proof, has to start early, almost in tune with the creative process.

As long as “versioning” takes place, whether by means of upgrading the back-end, porting it to a new framework or dispositif or translating the original experience into an installation (or, oh, why not, into a printed volume), the work and ideas that went into the original production stand a chance to live on.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.