Post #1 in the Making a New Reality series

By Kamal Sinclair

Emerging media cannot risk limited inclusion and suffer the same pitfalls of traditional media. The stakes are too high. Together, we must engineer robust inclusion into the process of imagining our future.

Given the major paradigm shift taking place across our communications architecture, the Making a New Reality research points to the urgent need to establish greater equality in emerging media before a new power balance is cemented.

The World Economic Forum is framing its agenda around the idea that we are in the dawn of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This means that emerging media are part of a suite of new technologies ushering in sweeping changes that have enormous promise for advancing civilization.

It is broadly acknowledged that, if misused, these emerging technologies pose powerful threats to the goal of creating a more equitable world. Emerging media pioneer Lynette Wallworth urges us to assess these changing times through more than just an economic or technological lens and consider how technological advancements instigated in silos and devoid of connection to community and culture, have brought about a new epoch in earth’s history the Anthropocene — an epoch that started with a war-time drive to split the atom. Theorists suggest that in this epoch humans are responsible for changing the natural world in ways that are irreversible.

We’ve learned from history that the stories and visual images we create have a direct impact on how we construct our future, access opportunity, and perform our identities within future environments. We’ve learned from history that it is impossible to understand all the unforeseen consequences of massive change, especially when those leading the change consistently suffer from significant blind spots in their perspective caused by a lack of diversity both in their real-world creative, business, and tech teams, and in their imagined visions of the future. Finally, we know from history that industrial revolutions or other paradigm-shifting moments in the functional design of civilization can bring great value to the world but at great cost to the most vulnerable.

The study of history often provides a strong predictor of human societal change. When history unexpectedly veers off course, it is usually due to a substantial technology advancement and the subsequent seismic changes it brings to business and economic systems. — Gunter Ollmann, Chief Security Officer, Vectra

It is imperative that we engineer robust participation of people from a broad set of communities, identity groups, value systems, and fields of knowledge in this emerging media landscape, in all roles and levels of power. This will help to mitigate the pitfalls of disruption and potentially usher in a change that has justice and equity as core values.

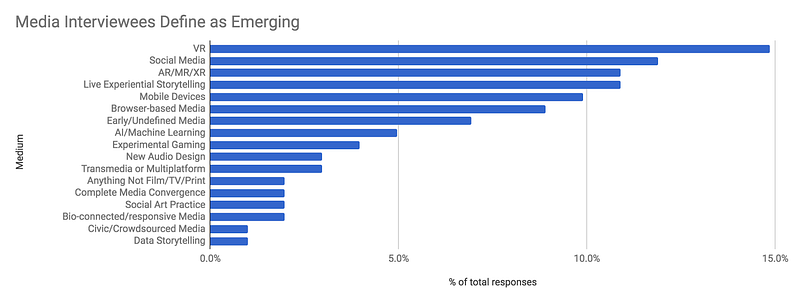

What are these emerging media forms? Here’s a quick summary from the Making a New Reality research. Read more about the research here.

Why are storytellers critical to this process?

Just imagine for a second that you lived in a world without stories. What would that look like? More than just a world without Jon Snow or Holden Caulfield, it would be a place defined by the absence of meaning. Something like an infinite number of isolated moments floating in space and time, with nothing to make sense of them or put them together in a logical sequence. Sound horrifying? It is. But here’s a real test to prove how fundamental storytelling is to our existence.

Read the following three sentences: He went to the store. Fred died. Sharon went hungry and wept. Did you assume that ‘he’ in the first sentence referred to Fred? Did you imagine that Fred died while at the store and that Sharon cried because Fred never came back? This simple test … reveals that the human mind is built to make connections and find meaning through stories. Since our daily lives play out mostly in the form of stories — complete with settings, characters and plots — it makes sense that our minds automatically process every new experience through mental story structures. Because our minds demand meaning, we even go so far as to invent stories and connections between events so that they fit into our mental narrative of reality. — Nayomi Chibana

Story and narrative are the code for humanity’s operating system. We have used stories to communicate knowledge, prescribe behavior, and imagine our futures since our earliest days. Story and narrative is how we design everything from the technology we invent, to the social systems we implement, to the norms in which we perform our identities, to perhaps the mutations of our very DNA and perceptions of reality (i.e. secondary trauma from stories). We are writing the next operating system for humanity with the stories we tell about our future. And those stories are now intertwined with computer code, which increasingly shapes what we perceive, know and feel.

“Code is the new superpower,” says Sep Kamvar, Lead researcher for MIT Media Lab’s Social Computing Group. “Code designs a social process, that social process designs our world.”

Since the dawn of mass media, the stories that frame our identities and systems have largely been told or controlled by a narrow few members of humanity. Even in 2017, the large majority of our global media is generated by or distributed on platforms that continue to be controlled by a small group of people who do not represent the diversity of our global population.

This history of mass media closely matches the history of political and economic imperialism. Historians have often attributed the success of European colonialism to military technologies, however, it is essential that we do not ignore the power of storytelling in conquest and domination. Stories are effective in priming participants with the rationale and ideology to implement these strategies (see An Indigenous People’s History of the United States; pp. 102–107 and 130–132). The pattern of using mass media to indoctrinate both aggressors and victims has been, and still is, problematic to the mission of bringing justice and well-being to humanity.

The design of past narrative “operating systems” had catastrophic “viruses,” because it excluded story coders who had knowledge of the firewalls that could have protected humanity. In fact, just before the turn of the 20th century many industrialized societies were still committing genocide or maintaining severe systems of oppression on indigenous story coders, rather than including their values and perspectives into the design of that period’s industrial revolution or “operating system.” That may have been the reason we failed to code environmental firewalls that might have protected us against climate change.

I’ve been delivering a lecture called “The Decolonization of Consciousness”… [I]t’s been a 400-year run of genocide and slavery that built the foundation for industrialization. Industrialization moving through all the natural resources, coal, uranium, oil… and moving us into a multinational corporate exploit, and we just got the bill, which is climate change. — Heather Rae, Indigenous Rights Activist and Filmmaker

Rae’s statement echoes the lived experience of Nyarri Morgan, who was the focus of the Emmy Award winning virtual reality project Collisions, a collaboration between Morgan, his family, VR creator Lynette Wallworth and producer Nicole Newnham-Malarkey. The fashioning of this story into a digital vision was made at the direct request of the Martu to Wallworth.

In the middle of the 20th century, Morgan was walking through the Australian interior, on land that the aboriginal people had stewarded for more than 50,000 years over 800 generations. He was stunned when suddenly the ominous mushroom cloud of an atomic test ascended, birds fell from the sky, and kangaroos were felled in the aftershock that rippled across the terrain. Morgan and the two family members he was traveling with took the meat, imagining it to be a gift from the Gods who had appeared in the stunning apparition. They shared it with their community and suffered what followed. This was 10 years “precontact,” so Morgan did not know people of European descent existed, that they had colonized his land and were testing weaponry on his traditional hunting grounds. Now, decades later, Morgan, the Martu people and their supporters — including Wallworth and Newnham-Malarkey — are actively fighting and generating tangible impact against the mining of uranium on the land Morgan’s people have stewarded for generations, and against the proliferation of nuclear testing around the globe, through the emerging immersive medium of VR.

This story symbolizes the broader relationship between technological advancements and the large majority of people excluded from the process of defining the value of new tools for humanity. Between 1895 and 1945, a relatively small group of people deliberated on how to use the power of atomic energy and determined that its greatest initial value was as a weapon. Morgan is one of hundreds of thousands of people who directly suffered as a consequence of this decision made without his inclusion, and one of billions who suffered in other ways, such as being inadvertently caught in Cold War Era conflicts. We are still working to mitigate the destructive power of that decision — witness current nuclear threats.

Again, we are in a defining moment for technology and media. Code has become a superpower. It informs or facilitates almost every aspect of our social, political, and commercial lives. However, most of humanity is fairly ignorant of how code works beyond the end-user interface. This harkens back to the centuries-old power structures that allowed the literate to rule the illiterate. Those who could read had power and, now, those who can code have power.

“VR is like uranium,” Jeremy Bailenson, the founding director of Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab told Wired in 2016. “It can heat homes and it can destroy nations.”

Jeremy Bailenson is referring to the fact that VR has been proven to have a direct impact on the psychology of the user. The power of virtual reality lies in its ability to immediately influence behavior and emotion. “We run the risk of having about 15% of the world’s population designing the world, through media consumption and media creation, for the other 85% of the population,” warns Julie Ann Crommett, the vice president of Multicultural Audience Engagement, at The Walt Disney Studios. “I don’t think that’s good business, first of all, but I also think that’s troubling from a societal perspective. Media consumption and creation is particularly precarious, because it does influence the way we understand and see the world.” This concern is echoed by the Co-founder of the Blackhouse Foundation, Brickson Diamond. He says “The risk becomes that we continue to have this really isolated group of people who decide what’s valuable.”

The notion of stewardship, of land rights and multi-generational care for the environment that exists in Nyarri Morgan’s cultural value system is in stark contrast to the short-term thinking of the Oppenheimer era and the economic drive of the mining industry.

What if, instead of being blindsided by the decision to use atomic energy as a weapon, Nyarri Morgan had been one of the people helping to define how it was used? Perhaps by telling his ancestral stories of land stewardship and kinship social systems he could have pointed the way to different possibilities. What bugs in our operating system might have been circumvented?

This is the opportunity we have in emerging media — to include Nyarri Morgan and his descendants among the people defining the value and purpose of our new extraordinary technological capabilities and telling stories that imagine the world we will transform into with these potential advancements. What kind of uses will today’s young Nyarri Morgans all over the world imagine for artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, supercomputing, and immersive media? What identity frameworks will they create for our future?

Profoundly, through Collisions, we’ve witnessed how emerging media can create some reconciliation with the missed inclusion opportunities of our past. In this project, a previously unincluded voice has become a leading voice in a critical discourse about how to resolve the consequences of innovations pursued with blind spots — climate change, nuclear proliferation, and sustainable land use — through a new medium that better serves the transfer of his knowledge and experience. Wallworth has often shared the story of how she and Nyarri looked at many different mediums that might serve as a channel to share his story, but in their estimation only VR was able to emulate the protocols of meeting on traditional lands, giving others a sense of his experience, culture and values. “When it comes to educating Australia and the wider world about culture and ‘caring for country,’ it’s this personalisation [achievable in VR] that can make the crucial difference in cultivating respect and concern for the land and its people,” suggests Wallworth.

As Collisions toured the world, Wallworth encountered others who found this medium ideal for sharing their knowledge and experience. “Nicole [Newnham- Malarkey] and I continue to be invited to carry these technologies, and a decades-long approach to making meaning with them, into a select few communities that want a message to be sent out via a new portal. The technologies are not superior, they are adequate vessels to hold the seed of complex world views, synthesised into a digital drama, as a real attempt at connection, illumination, and in the hope of effecting real world change. In the world of the Martu, time does not move in a straight line, the digital ‘meeting’ of Nyarri [Morgan] and Oppenheimer, a conversation that historically did not happen, is constructed inside the work…and so evokes a new outcome, one where Nyarri’s voice is heard. The subsequent travelling of the story, worldwide in 2016, evidenced just that. Martu hold certain stories as children, until there comes a ‘right’ time for them to be released into the world. The timing of the decimation of Collisions, just a year before an unexpected ramping up of nuclear threat, is not accidental, rather, it is of the nature of Martu technology, the mastery of story/time/place that is gifted into Collisions. The coalescing of these different forms of technological ‘mastery’ is what I am intent on pursuing.”

The message was heard. Wallworth was voted one of a hundred leading global thinkers by Foreign Policy magazine, who chose these leaders because they subverted “traditional power structures to craft solutions to social, economic, and environmental problems.”

In The Fourth Industrial Revolution, Klaus Schwab writes about both the great promise and peril humanity is facing. People can be dramatically more connected, organizations more efficient, and there’s the potential to reverse some of the ravages of previous industrial revolutions. Yet there are many dangers — fragile organizations, governments unable to adapt fast enough, shifts in power and inequality, the crumbling of the social fabric. The suite of technologies coming with the current paradigm shift are arguably more powerful than atomic energy. For thought leaders like Schwab, the key is collaboration — across the world, different professions and disciplines — to take advantage of the positive aspects of this massive shift.

However, we are already repeating the same mistakes. A narrow group of people are deciding the value of these technologies, and are typically the ones also benefiting economically from their implementation. What viruses will emerge as a result? What are the consequences of repeating this pattern of exclusion?

We have a window of opportunity to break this pattern and create an inclusive process for designing our future. Many of those interviewed in this research expressed an urgency to seize this window of opportunity, as we cannot afford to have a small fraction of our global community define the values and features of our next operating system.

In the months that follow, we will be sharing specific ideas about how we can ensure emerging media and the process of imagining the future includes us all. Follow along with us at the Making a New Reality site. There you will find the bulk of the research in support articles.

This month’s support articles synthesize answers to the question, “What is emerging media?” Don’t miss:

The Making a New Reality research project is authored by Kamal Sinclair with support from the Ford Foundation JustFilms program and supplemental support from the Sundance Institute. Learn more about the goals and methods of this research, who produced it, and the interviewees whose insights inform the analysis.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.