The Trouble with Nonfiction Transmedia

An Immerse response

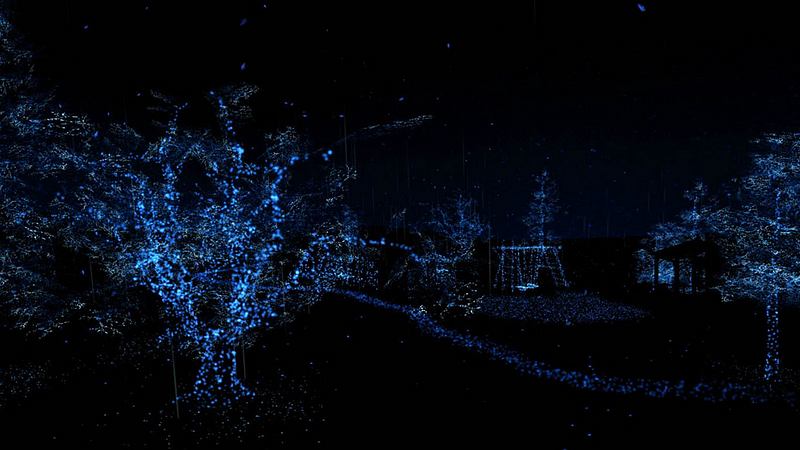

As a documentary filmmaker, as well as a researcher at MIT’s Open Documentary Lab, I am both curious and enthusiastic about the creative possibilities of nonfiction transmedia projects such as Notes on Blindness, which chronicles the experience of going blind in a short film distributed online, a feature film, and a series of VR experiences. In the lab’s Docubase, I’ve curated a playlist of other notable nonfiction transmedia projects.

Transmedia approaches offer creators the ability to move a narrative beyond the traditional three-act structure often demanded by funders, explore different subjectivities, engage a community in an ongoing conversation, and tell stories in innovative ways.

Creating connected stories across multiple platforms also magnifies the vast potential of nonfiction worldbuilding. While worldbuilding usually refers to the practice of creating expansive, detailed fictional universes for science fiction or fantasy works, it is also a constructive lens through which to view and explore the narrative structure of transmedia projects. Nonfiction worldbuilders can also experiment with new modes of participation, share more of their stories, and more fully understand the “worlds” comprising creators, subjects, and audiences.

Some of this potential is reflected in work currently being produced by documentary and legacy media institutions. Driven by a desire to expand audiences in an age of media fragmentation, and to reach younger audiences in particular, media organizations such asPBS, the NFB, and The New York Times are eagerly producing nonfiction transmedia projects. For example, Frontline’s Ebola Outbreak included a broadcast program, a VR documentary, and short web videos created in collaboration with The New York Times.

Learn more

about Ebola Outbreak: A

Virtual Journey

Learn more

about Ebola Outbreak: A

Virtual JourneyTransmedia approaches also feature heavily in “impact” strategy and assessment, now a critical factor in documentary funding. These motivations, in addition to brand-building and innovation rhetoric, are making broadcasters and networks major drivers of transmedia projects; increasingly, filmmakers are required to deliver digital components along with their films.

On the surface, this push for creative approaches to documentary is a positive development that goes unmentioned by Andrea Phillips. Many compelling and innovative projects have emerged from this seemingly robust arena of transmedia creation. However, in my research for MIT’s Open Doc Lab, I’ve encountered a great deal of uncertainty among producers, creators, and other industry stakeholders when it comes to transmedia. The challenges of producing transmedia are substantial: creators are required to navigate divergent production processes, constituencies, funding and distribution models, and temporalities across different industries.

On a larger scale, there is substantial confusion around the motivation for creating transmedia works in the first place. Institutions’ focus on transmedia is largely driven by vague economic imperatives, as well as impact rhetoric that many agree is overly simplistic. While legacy media institutions are publicly sanguine about transmedia projects’ ability to reach larger and younger audiences, it’s unclear how to best measure their reach and effectiveness: many creators are unsure about who the audiences actually are for these projects, as well as what kinds of metrics are available or accurate. As Phillips points out, reaching audiences in today’s saturated media ecosystem is challenging, and monetization is still a problem.

Furthermore, much of the work being produced fits a restrictive template: a broadcast or feature documentary with an accompanying interactive web component or, more frequently now, a VR piece. The centralization of transmedia teams around specific media organizations can also result in uniform results in terms of aesthetics, narrative structure, or conceptions of audience. Meanwhile, many creators used to working in film resent funding imperatives focusing on digital media, and feel pressured to master a growing range of tech literacies.

In short, documentary and legacy media institutions’ current focus on transmedia approaches often prioritizes their ability to build markets and audiences, rather than their ability to expand narratives or enrich conversations. At the same time, there are exciting storytelling, community building, and experiential possibilities that are being neglected.

This situation echoes some of the transmedia deflation that Phillips discusses. What is the solution? More open and critical discourse around transmedia would be a good start — not only keeping an open mind about what nonfiction transmedia looks like, but also sharing both frustrations and solutions in order to nurture transmedia literacy and a wider community of practice. Transmedia approaches are a fact of today’s media ecosystem, and it would be a shame for both creators and audiences if their creative and connective potentials are not fully explored.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT OpenDocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.