Speculative nonfictions and Augmented Reality in public space

by Amy Rose

Augmented Reality is the name given to a layering technique enabled by recent technological developments. It is a broad and bizarre umbrella — encompassing Snapchat lenses that turn your head into a cucumber, Instagram filters that perfect your imperfect skin and immersive audio “grime rap operas” triggered by your movement through a place.

As smart phones develop, the kind of layering develops. To put it simply, adding on top of what you can see is easy and taking anything away is hard. Of course, it is only a matter of time before this changes.

In 2020, Augmented Reality was given an unexpected boost.

While live events disappeared with barely a trace, interest spiked in “access-anywhere” culture and entertainment. This encouraged a boom in home-based subscription services, like Netflix. It also increased reliance on digital devices, particularly smartphones, as the route to culture and togetherness — and refocused our gaze at the street as a place to do things.

The street, in fact, isn’t quite what it was in 2019. There is a sense of safety in being outside that is peculiar to the pandemic, though the ambiguity of this idea of safety is critical. One person’s blissfully airy pavement is another person’s site of potential harassment and violence.

Despite (or perhaps alongside) this ambiguity, AR can flourish on these streets. What can be unearthed by a carefully chosen and crafted layer? What can be said — that is palpable, but unsaid?

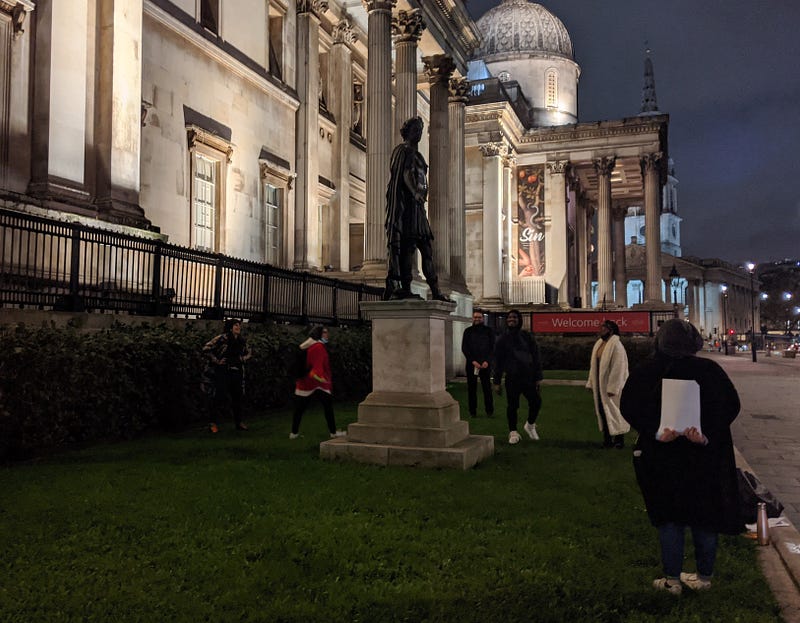

Holding these complexities in mind, I stand with a small group in Central London. It is November 2020 — cold, but dry and the lights are bright. People are lounging. Central London has a buzz about it in the evenings.

Assistant

Producer Sahar Malik underneath a statue of James II in Trafalgar Square

Assistant

Producer Sahar Malik underneath a statue of James II in Trafalgar SquareWe are looking at a statue of James II — smaller than Nelson on his nearby giant column, James is just in front of the National Gallery next to Trafalgar Square. The lawn is perfectly manicured. King of England for just three years (1685–88), he was Lord Admiral of the Navy for decades and the first leader of the Royal African Company. By the 1680s, the RAC was transporting around 5000 enslaved people every year to markets in the Caribbean.

This man made of metal, dressed up to look like a triumphant Caesar, stands on a plinth made of stone. There is no mention of the RAC on the plinth. Sahar, our assistant producer, tells us that many of the enslaved people taken by the RAC were branded with the letters DoY on their chests. James was the Duke of York. The group is mostly people of colour and the chill is tangible as the word branding hangs in the air.

We are trying to work out how to communicate the story of this man. What details bring it into sharp relief — bring him into our present presence? How do we honour the connection between his story and the story of the England we live in now?

And for now — what can AR as a medium offer this sort of challenge?

From Augmentation to Subversion

Calling Augmented Reality a layering technique comes at it from a technical perspective, rather than a perspective that prioritises experience or meaning.

What is the “reality” at play in Trafalgar Square, gazing up at James II? One of the realities is that I could, soon, get ten years in jail for vandalising his form. And what is “augmentation?” What does it enable in our experience of the place?

Augmentation brings up associations of Botox and plastic surgery — just a little bit of something extra to plump out the cheeks. But what if AR is a way of reframing or challenging your relationship with a place? A medium that provides an alternative, slightly skew-whiff perspective on the apparent rules and stories at play.

From Frankenstein to The Left Hand of Darkness, speculative fiction novels have long offered a lens through which we can gaze at ourselves — and subvert the norms by which we live. Perhaps Augmented Reality is a new form of speculative fiction that allows us to perceive the possible or actual dynamics bubbling along, the cucumber heads we are all secretly hiding.

If we treat it like this — how does it affect our starting position, as makers? What is worth unearthing — and how can this help us tackle the unseen forces that impact our lives?

In a way, this is a rethink of what non-fiction means. If the experience demands participation in something that happens in public space — a real experience in a real place — it is hard to call it fiction. Something else is at play, some other category developing. Perhaps speculative non-fiction is more appropriate for this new form.

The Battle Between Ears and Eyes

The development of visual AR is at its most fast-moving and ubiquitous on Snapchat and Instagram. Both platforms specialise in ephemeral content. You look, you swipe, you close the app. While it’s entertaining to see yourself with a dog’s nose, these moments flit past on the wind. Institutions have taken organized visual AR outdoor “exhibitions” and the Smithsonian has digitised its objects so you can conjure the skeleton of a dinosaur wherever you are.

AR filter

from the Smithsonian Museum on Instagram

AR filter

from the Smithsonian Museum on InstagramAudio AR is something else. With longer roots that touch artists from Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller to Duncan Speakman, sound works for public spaces have been under construction for decades, long before the GPS-enabled smart phone became pervasive.

Often categorised as an “accompanying medium” — implying that it’s not the main event and you can still get on with the important business of living — sound hits us, soaks in and resides within us in a profoundly different manner to the visual. Sound in public space can subvert the built environment in a way that invites a different sort of engagement than an AR filter.

Unlike looking at a tiny screen, the freedom given by listening enables a form of engagement that is more languid and gives more agency — you can wander around, and the movement of your body becomes an element of your experience. The frame itself shifts — from a carefully composed window to an internal perspective that casts the world in a different light.

Image

documentation from the audio “subtle mob” project, “As If It Were the Last Time,” from Circumstance,

established in 2010 as a framework for the collaborations of Duncan Speakman, Sarah Anderson and

Emilie Grenier

Image

documentation from the audio “subtle mob” project, “As If It Were the Last Time,” from Circumstance,

established in 2010 as a framework for the collaborations of Duncan Speakman, Sarah Anderson and

Emilie GrenierThe Rules of the Space

From fancy bridges to pedestrianised shopping centres, many urban public spaces are owned by private companies who police them with security guards in branded high-vis. Invisible rules govern these ostensibly “public” spaces.

This matters if the intention is to subvert or unearth the realities at play. Certain kinds of public art have often been installed hand-in-hand with the regeneration of urban areas but, as friendly as the street furniture looks, the rights of private property (and those who own it) are sacrosanct across the Western capitalist world. You and your rights are as important as a speck of dust in comparison.

The “subtle mobs” by Duncan Speakman are a great example of work that manages to be subversive and expansive in this context of contested public space. With a subtle mob, you download the audio and then turn up in a specific place at a specific time — and listen. You’re hiding in plain sight, on headphones. The work is invisible.

Who are These Publics?

It should be more clear than ever before that the way someone feels in a public space can vary dramatically, based on their personal identity and perspective. And the pandemic has intensified these dynamics — with fears of the unknown Other and the germs they carry layering on top of the already complex Otherings at play in any public space.

It’s easy for artists to underestimate these simmering human dynamics. What is embarrassing? What is exciting? How do those passing strangers make you feel?

What if these powerful sensations are recognized or integrated into the design of a piece? Giving people permission to feel what they feel and then move beyond it into a space slightly unfamiliar — this sense of a welcome matters to an audience member in an uncontrolled space.

A group of

researchers and artists gather around a statue of James II in Trafalgar Square

A group of

researchers and artists gather around a statue of James II in Trafalgar SquareAs debate rages across the UK about what is permissible in public space (and what sentences we might be subjected to if we actively disagree with the curation of those public spaces), the role of the digital seems increasingly important. In this context, Augmenting Reality by subverting the dominant stories of a place is a way of occupying a liminal edgeland zone in the public conversation.

Back in Trafalgar Square, we discuss the challenge of telling a complex story on a device that is often associated with ephemeral content — as well as working within the limitations of the current technologies available to most people.

The original plan was to digitally disrupt the image of James by setting him on fire or melting him into a pool of blood. With the reality of normal smart phones fully explored (those that most people have, rather than the latest iPhone), the conversation turns to sound and what is in the air around this relic of our Imperial age of conquest and violence.

The project becomes about the ghosts that haunt the air around him — the ghosts of England, wailing their laments, infiltrating our dreams.

Ghosts of Solid Air is an interactive story about the statues we live with — and the ghosts that haunt them. Who are the ghosts of England? And who could they be — if you took control of the story? This interactive AR app invites you to act, to play and to disrupt the stony figures we find on pedestals across our pavements. Currently in development at Anagram and co-created with a group of non-professional community producers, it will be launched in 2022. Funded by a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council and co-produced with Dr Colin Sterling (UCL & University of Amsterdam).

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.