This Is the Moment for Visionary Narratives

There is how we tell a story, and then there is the story we tell.

The Detroit

Narrative Agency is inventing new ways to tell community stories.

The Detroit

Narrative Agency is inventing new ways to tell community stories.It feels like new media platforms launch every day, but are only being used to tell the same old stories, enforcing the current limits of our collective imagination.

And it is clearer than ever that we are currently trapped inside the imagination of people who are not committed to a future that includes us, or even happens on this planet.

There is a body of people across the globe whose ancestors organized the world around a few core ideas that are incompatible with human survival on earth, who imagined themselves as white royalty amongst black and brown masses, who bent policy, economy and culture to realize this imagined supremacy.

And now we are in it, and it is in us.

Now we need to be the storytellers of the next phase of the future. And we need to concern ourselves not just with the content of our liberating imaginings, but with how we will imagine together.

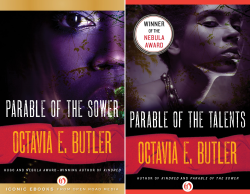

Octavia Butler predicted this moment in her Parables: a president elected on a platform of white nationalism, misogyny and anti-intellectualism — even down to the slogan “Make America Great Again.”

Butler was a black science fiction writer, and her vision was radical. She was able to imagine the patterns of the news cycles unfurling in the future, to tell us about the most likely outcomes, and the new problems we would face. This year, a decade after her death, her stories are painfully coming to life.

The good news is that her imagination and research provide us with survival techniques that storytellers across all platforms can study.

Those who own the companies that shape our communications look like those who run the banks, military and government, the sheriffs and police chiefs. Younger, but still white, male, concerned with “diversity” as an afterthought or an act of benevolence, celebrating themselves as innovators. They are millionaires and billionaires slowly consolidating all the ways we build patterns with each other, accountable primarily to themselves and their investors.

So in addition to the work of building the muscle of our imaginations, we must build the pathways by which we reach other, make sure we can hear each other beyond the status quo.

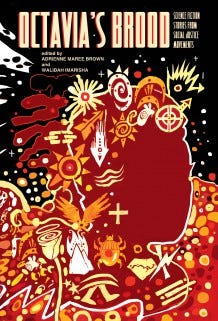

In terms of telling our own stories and generating new questions and problems that are relevant for currently marginalized peoples, Walidah Imarisha and I edited Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements. We asked people who are organizing in a variety of movements in the US to write visionary fiction about the horizons they see.

“Visionary fiction” speaks of art that is self-aware, that understands there is no such thing as neutral — art either advances or regresses our evolution, justice and liberation. We use the term to identify work that centers marginalized communities, understands change as a bottom-up process, challenges single hero narratives and moves beyond the binary of dystopia/utopia. It was important for us to gather these stories from people doing the work, because we believe that all organizing is science fiction, shaping the future to be a just and liberated place.

We aren’t the beginning of visionary fiction, and Butler isn’t the only one who was writing it. The work of Samuel Delaney, Steven Barnes, Nalo Hopkinson, Walter Mosley (particularly Futureland), Sheree Renee Thomas (the Dark Matter anthologies), Nnedi Okorafor, Ursula Le Guin, Tananarive Due, Doris Lessig, Marge Piercy and many others fits this category.

But imagination is only the first step. We have to get our stories to the people. Now there are many ways to do so.

We are engaged in a narrative shifting experiment in Detroit right now called the Detroit Narrative Agency (DNA). Supported by Just Films at the Ford Foundation, we are supporting a cohort of ten filmmakers — from first timers to experienced camera people — to create fiction and documentary moving image projects that challenge existing narratives about Detroit.

To grow this project from community soil, we asked Detroiters what stories they were tired of hearing (anti-blackness, anti-poor, that the city is a blank canvas or a murder hub, or needs white saviors) and which stories they wanted to hear much more of (stories of black resistance and resilience, long-term survival and visions of the future). We then held an open application process shaped by that longing.

The body that selected the projects was made up of local artists and activists who are compelled by the same narrative needs as the applicants. The cohort is mostly black, mostly lifelong Detroiters, with balance in the areas of gender, sexuality and age. They are excited to be in each other’s presence, and are teaching and supporting each other.

We collectivized the purchasing of equipment so our cohort can use high-quality equipment to make their community-rooted narratives, because we recognize that these days aesthetic really determines which pieces get watched and shared with others. We are generating beautiful, well-structured projects.

We have matched each project up with mentors in the industry and are hosting a series of workshops for the cohort, each one paired with public events so that this expertise and wisdom is available to the whole community. We are exploring distribution options that will bring these projects to the public for feedback and interactions that create more possibilities for Detroit. Our projects will culminate with completed budgets, timelines, community engagement/impact strategies, scripts/screenplays and trailer/teasers that will allow them to leverage this opportunity for full project funding.

Each of our choices around who to select and how to identify community priorities is a precision technology that increases the relevance of the media that our cohort will produce.

Only after we were excited by the stories our filmmakers want to tell, stories that challenge the existing paradigms of power and patterns of gentrification in the city of Detroit, only after we were certain we had changemakers at the table, did we get excited by the new ways our cohort wants to tell its stories.

One shift in the use of media is where our filmmakers want to take audiences — disrupting the “talking head in an office = expert” trend. Who is Sitting on Our Land is going to take viewers into the field to speak with farmers who face displacement in the city. Riding with Aunt DDot is going to take us onto the bus lines to see how people are surviving, uplifting each other and traversing the city.

We have three narrative projects exploring future Detroit through the eyes of young black people shaping and changing the world — Ada, The Growers, and When It All Changed, an experiment in interactive virtual reality, bringing viewers into a distant future articulated by Detroit youth.

So much of the work I do with DNA, and in Detroit, and anywhere I facilitate or write, is about emergent strategy — strategies that allow us to be in right relationship with change and to use everything available to us to shape the future for justice and liberation.

Even when the future appears to be frightening, there is opportunity inside it for us to advance our humanity, to deepen our relationship to this planet, to tell new stories of collaboration and miraculous evolutions.

This has to be an exciting time. Our work as creatives, filmmakers, activists, and storytellers, is to answer Toni Cade Bambara’s call “to make the revolution irresistible” and, I would argue, to sustain us when the odds don’t appear to be in our favor. We must deploy every tool in the box for the sake of ourselves and future generations.

Read responses to this piece

How Can We Use New Storytelling Tools to Explore Visionary Futures? by M. Asli Dukan

Building Visionary Non-fiction By, About and for Our Communities by Michele Stephenson

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.