Journeying through the many avatars of Elaine Hindin, TikTok’s 85-year-old crypto-influencer

Elaine Hindin’s TikTok page is filled with animated apes that are potted like plants and decked out in accessories. In one of the pinned videos, a chimpanzee with long, flowing hair and lavish jewelry tells viewers, “You’re only one video away from going viral.” The animation, named K.K. CELEBRITY, is a spoof on Kim Kardashian.

“K.K.” is a spoof of Kim

Kardashian. In this recent iteration, Hindin alludes to Kardashian’s recent safari.

“K.K.” is a spoof of Kim

Kardashian. In this recent iteration, Hindin alludes to Kardashian’s recent safari.TikTok draws such a young audience that consumer data company Statista lumps all users over 50 into one category — this demographic makes up 11% of the app’s traffic, about half the size of each of the other age groups. Hindin is 85. The artist considers the platform an exercise in balancing creating for herself with the algorithm’s preference for trends. “TikTok art is created backwards,” she says. “You find a trending subject and create from it.”

Hindin has been adapting her artwork to changing technology since the 1980s. Her projects blend popular culture with a more organic, avant-garde aesthetic. The result is bizarre and amusing work that is deeply rooted in social commentary.

Talking Plants, Hindin’s series of potted apes, originated as NFTs. Part of Hindin’s intent was to poke fun at the Bored Ape Yacht Club, a Miami-born collection of colorful ape portrait NFTs popular among crypto and celebrity buyers. It’s no secret that blockchain technology is mostly a boys’ club. Google Analytics shows that more than 85% of user engagement with Bitcoin, for instance, is male. And, according to Bloomberg, just 5% of NFTs sold between February, 2020 and November, 2021 were made by female artists. Hindin’s aim with Talking Plants is to present a satirical take on the male-dominated collection.

“[Talking Plants] has to do with me as a feminist — boy, I am really a feminist,” Hindin says. “I think guys are running all the techy stuff, and now they’re just shoving it down our throats.”

A Lifetime of Experimenting

Early on the morning of February 2, 1976, Hindin grabbed her yellow rain slicker, camera, and 400- millimeter lens to head into a cyclone. She lived in Maine at the time and drove her Saab out to a stretch of coastline about two hours north. For seven hours, she clung to a bush and photographed sheets of water, snow and hail cutting through wind and brief patches of sunlight.

“The time passed in a way that I never experienced,” Hindin says. “It seemed like maybe minutes had passed.”

The storm galvanized Hindin to create. Her paintings became more abstract, and she turned to physics and metaphysics to make sense of her experience. With her husband gone for business more often than not, she grew restless with the isolation of motherhood in rural Maine. She moved with her daughters to California and filed for divorce.

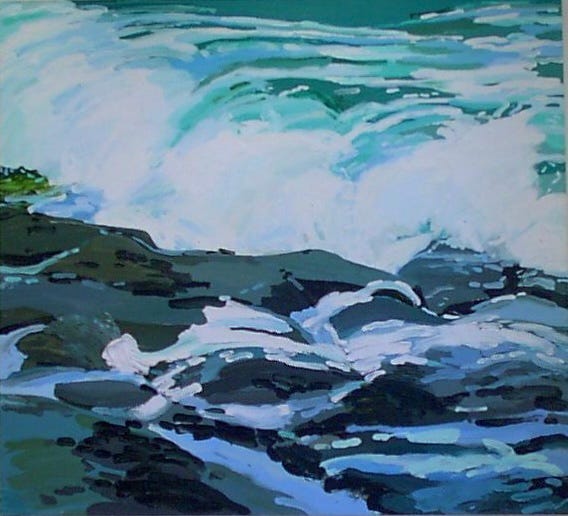

One of

Hindin’s paintings depicting a cyclone in Maine, 1976

One of

Hindin’s paintings depicting a cyclone in Maine, 1976One of Hindin’s first technologically influenced works of art was the “telejectron.” She had already grown dissatisfied with painting as a medium for conveying her experience in the storm and created an immersive installation to emulate it instead. The telejectron took this a step further by using holography, coupled with specific lighting and electronic music, to evoke an altered state of consciousness. The many-faced, sharply angled structure took up most of Hindin’s living room, allowing visitors to sit inside of it. The project helped Hindin land an artist residency sponsored by the California Arts Council and City of Santa Cruz.

A photo of

Hindin (formerly Yanow) with her telejectron, taken for the Santa Cruz Sentinel, 1982

A photo of

Hindin (formerly Yanow) with her telejectron, taken for the Santa Cruz Sentinel, 1982

Becoming the Simulation

Both installations and mechanization were gaining popularity in contemporary art upon Hindin’s completion of the telejectron. Personal computers, invented in 1974, were also becoming mainstream. In 1986, F. Randall Farmer and Chip Morningstar invented the avatar.

As technological innovation skyrocketed, so too did fantastical depictions of it within popular culture. Movies like Back to the Future (1985) and songs like Mr. Roboto (1983) played with concepts real and imagined, like time travel and artificial intelligence. In 1985, a British television company introduced Max Headroom, a supposedly computer-generated program host. The “AI character” was played by an actor whose appearance was altered using makeup, harsh lighting, and special effects.

Hindin was fascinated by Max Headroom and decided to develop a female version. She dressed her daughter in thrifted clothing and photographed her as “Hedda Talespin,” a parody of 1940s gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. She wanted to create a digital avatar, but at the time, CGI was inaccessible to the average person.

Into the Digital Age

The 1994 Northcon Electronics Convention in Seattle came off the heels of the globe’s first World Wide Web conference. By that time, Hindin was working as a technical writer for Puget Sound Energy in Seattle (and moonlighting as a competitive ballroom dancer).

In a vast room filled with mostly male attendees, Hindin spotted a man with wiry glasses sitting in front of a black-and-white Macintosh Classic, an ancestor of today’s Apple computers.

“What are you doing?” Hindin asked the man. He told her he was programming a webpage.

“What’s that?” she asked.

The man invited her to sit down, and he showed her how to code. Hindin doesn’t remember her one-time teacher’s name, but his lesson changed her life.

“I just took off from there,” she says. “I mean, I went out, I bought a Mac classic. I studied HTML programming.” Around this time, as home computers became increasingly common, the number of women working as coders plummeted. NPR attributes this trend to a concurrent rise of the narrative of digital “techie” space as masculine.

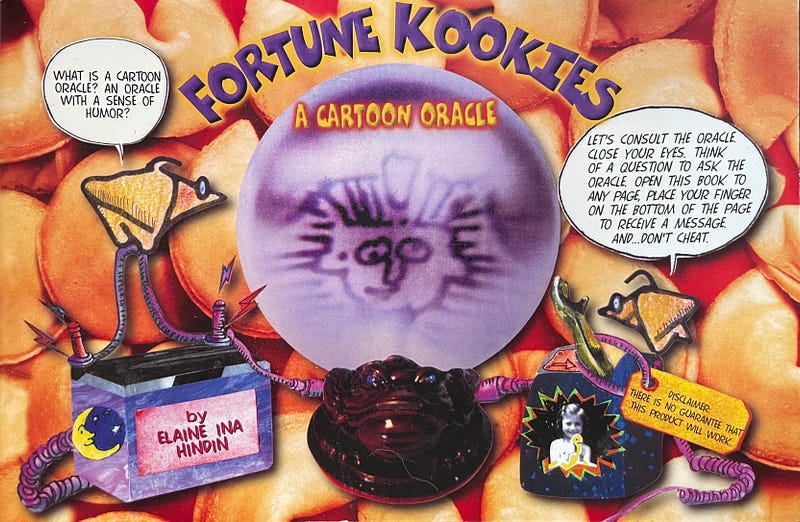

Two months after the convention in Washington, Hindin completed her first digital project: a series of 108 comics drawn using a bitmap program. She printed them out and published them in her book Fortune Kookies: A Cartoon Oracle. The cover instructs readers to think of a question and open to a random page for the answer. (I asked the copy Hindin mailed to me if I was going to have a good summer. I opened it to a page with an acupuncturist’s diagram of the human body along with a joke about botching a medical procedure. Italicized text at the bottom read, Learn from your mistakes.

Smaller, Better, Faster, Stronger

Hindin has used increasingly advanced software over the decades. She now creates all her content using apps.

“My impetus now is to make things that people can project on their wall,” Hindin says. “I’m trying to make things for people that can actually be portable, and they could change the pictures anytime they want.”

Hindin’s daughter, Alexandra Sokol — the pre-Internet model for Hedda Talespin — says her mother’s artwork has changed dramatically in the digital age.

“She went from creating art that was like 8 by 10 feet — wall space museum pieces — to getting smaller,” says Sokol. “She’s able to churn things out so much faster.”

During her foray onto social media over the past few years, Hindin decided to stop selling her physical paintings through a local gallery. The pandemic forced her to sell all her work digitally, so she figured she might as well create everything digitally. Since then, it’s been up to her to market her work.

Finding her Niche

Hindin hasn’t had much luck trying to sell her NFTs on OpenSea. She says the market has become too competitive.

“It is exclusive, it’s overcrowded,” she says. “So now you’re right back again to the way the New York art scene was.”

After several months and little demonstrated interest from potential buyers, Hindin decided not to drop her collection on OpenSea. That’s when she turned to TikTok, where she adapts talking plants for a different audience. Hindin joined the platform this past March and is slowly building a following, so far of 334.

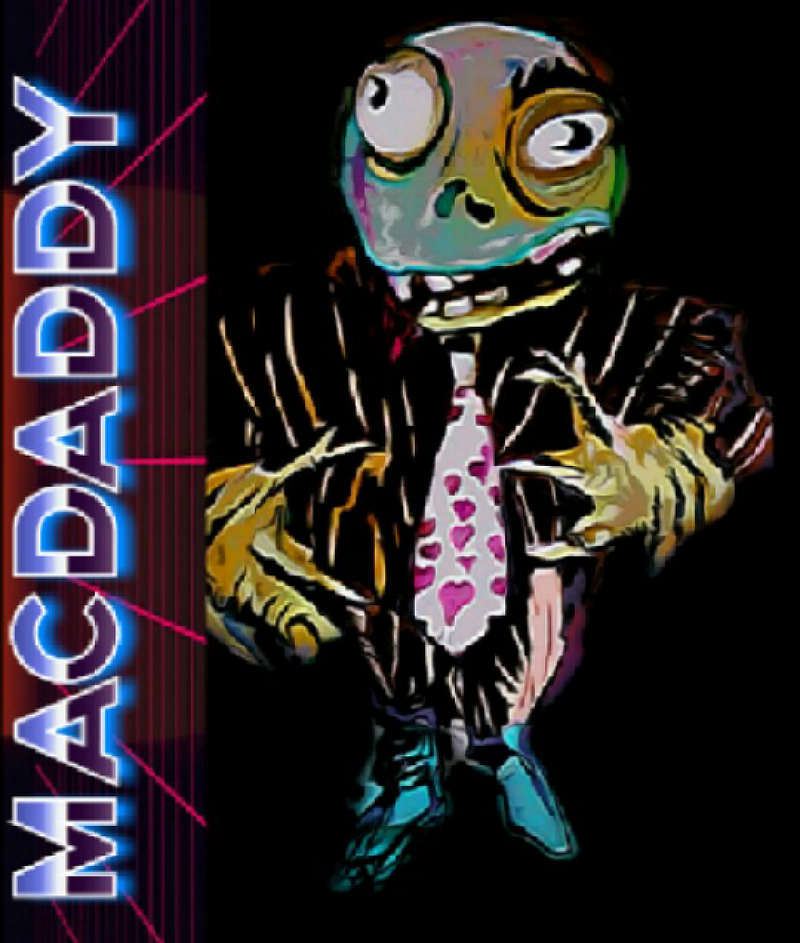

Talking plants are not the only characters to grace Hindin’s social media pages. Her artwork has delved into a range of recurring and often bizarre personalities. Around the 2020 election, she debuted a Plants vs. Zombies-looking character named MacDaddy.

“MacDaddy is what I jokingly call a day-trading toad,” says Hindin. “He’s your quintessential sleazeball, and he thinks of himself as being innocent all the time.”

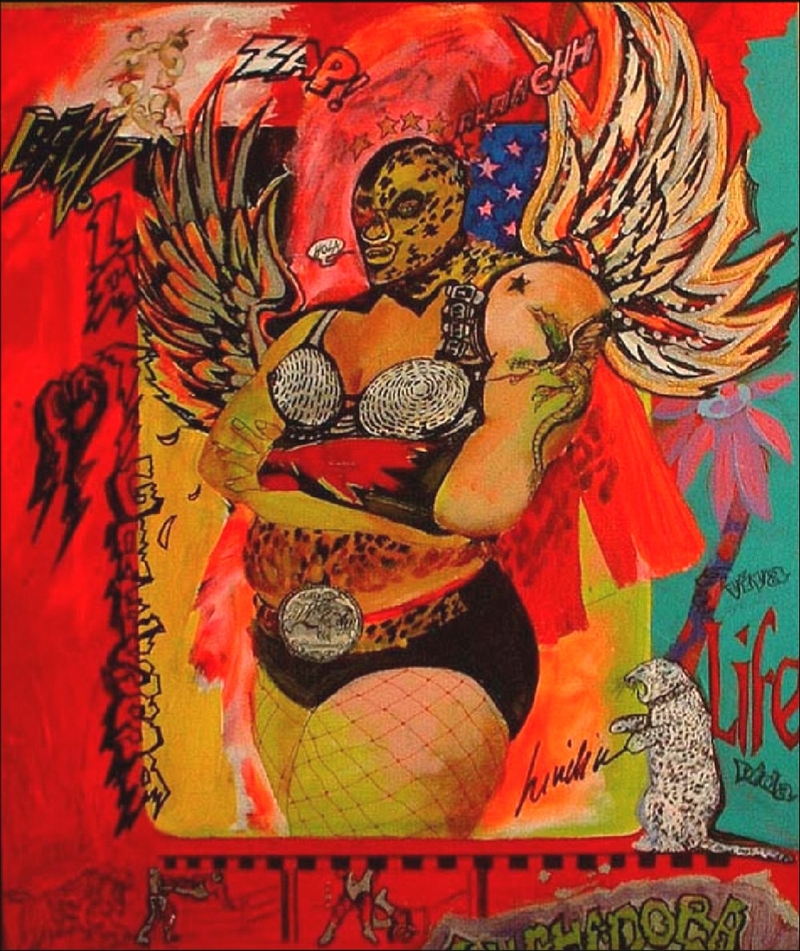

One of Hindin’s other characters evolved from an analog series. Many of her paintings feature scantily clad, tattooed women posing before maximalist, often fantastical backgrounds. Her “Luchadoras” are no exception. The series depicts fictionalized versions of female, Mexican professional wrestlers. Hindin was inspired upon learning that many luchadores were grandmothers or single moms learning to provide for their families. “Bird Woman” was one of Hindin’s luchadoras, and a crime-fighting superhero. Hindin extended Bird Woman’s story into a digital series in 2018.

A painting of Bird Woman, part of

Hindin’s “Luchadora” series who eventually became her own digital spinoff

A painting of Bird Woman, part of

Hindin’s “Luchadora” series who eventually became her own digital spinoffLearning to create digital characters has allowed Hindin to finally make Hedda Talespin a virtual reality. In 2021, she deemed the figure, a plastic-looking, made-up face on a disembodied head, her personal avatar. The alter-ego in a way cements Hindin’s journey from analog to digital artist.

“The whole art world has radically changed, I mean, it’s off the canvas,” Hindin says.

Hedda

Talespin, Hindin’s avatar

Hedda

Talespin, Hindin’s avatarOperating under an avatar also veils Hindin’s age, which she sees, aside from her living memory of history, as irrelevant in her creative life. “I’ve always been 20 years ahead of my time, and I can’t speak for people of my generation, because I’ve never really [identified] with that,” she says.

A little over 100 videos down Hindin’s TikTok page is one of Hedda Talespin, her disembodied face ringed by staticky, blue and yellow light.

“She’s just my avatar, so she’s become electronic,” Hindin explains. “She’s an AI character now.”

Elaine Hindin at the San Diego

County Fair in 2013

Elaine Hindin at the San Diego

County Fair in 2013