Transmedia What?

What people new to the concept often do not understand is that transmedia is an adjective in search of a noun to modify.

“Transmedia,” by itself, simply describes some kind of structured relationship between different media platforms and practices. Initially, it was a practice identified more closely with fictional work. More recently, however, producers of nonfiction transmedia have been using these techniques to tell their stories “by any media necessary,” taking advantage of whatever resources they can access as long as they can meaningfully deploy them in the service of their goals.

When Marsha Kinder wrote about transmedia in Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games (1993), she was describing a set of iconic characters, such as the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or the Super Mario Brothers, who were recognizable across a range of media platforms, even if there was little or no integration of their stories. When I wrote about transmedia storytelling in Convergence Culture (2006), I ended up discussing a range of different experiments both at the heart of Hollywood (The Matrix franchise, Dawson’s Desktop) and on the edges (the emergence of alternative reality games).

When Andrea Phillips writes that transmedia “as I once knew it was, as Brian Clark would have said, an art scene encompassing a particular group of creators doing some things in common, largely springing up around the space that used to be alternate reality games,” she is describing one particular tribe — what Clark himself half-jokingly labeled “the East Coast School.” This tribe has created some of the most exciting transmedia art projects in recent years, but it represents one subset of a larger phenomenon.

We need to distinguish transmedia from multimedia and cross-platform:

- Transmedia approaches are multimodal (in that they deploy the affordances of more than one medium), intertextual (in that each of these platforms offers unique content that contributes to our experience of the whole) and dispersed (in that the viewer constructs an understanding of the core ideas through encounters across multiple platforms).

- As I use the terms, cross-platform refers to delivery channels: if the same documentary — say, 13th — appears simultaneously in theaters and on Netflix and perhaps down the line on DVD, then we can describe it as benefiting from cross-platform distribution. But there is no opportunity here for additive comprehension, no real reason for the same consumer to visit these various hubs to learn anything new.

- Multimedia refers to the case where a single app or website might include video, audio, text, and simulations (see, for example, The New York Times’ 2012 Snow Fall, whereas a transmedia project may distribute these experiences across platforms so that the audience must actively work, often through networked consumption, to assemble the pieces.

These distinctions are far more important than the often asked question of how many different media must be involved in order for something to become transmedia: the core question is not how many media but what kind of relationship exists between them, what kind of contributions do they each make, and what cognitive and social activities do they require from their spectators.

An independent or documentary producer should start with a broader conception of the media that surround them. We can imagine, for example, the use of lower cost media such as podcasts or tweets or web video (as was deployed in The Lucy Bennett Diaries) or perhaps live and location specific experiences (such as dramatic or musical performances, street art, augmented reality games, audio guides, or museum exhibitions).

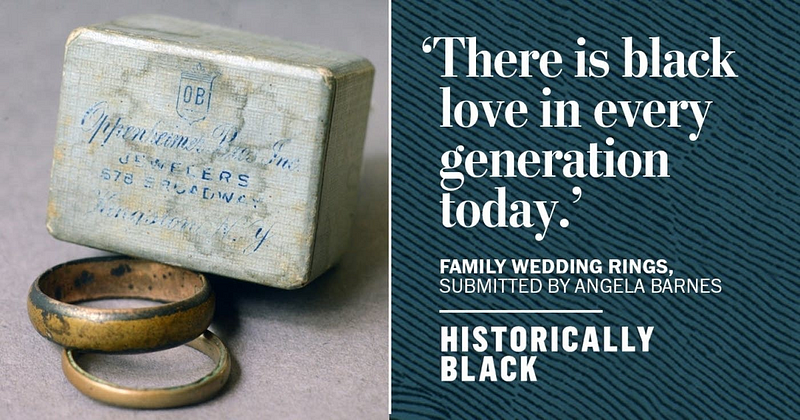

Consider, for example, the Historically Black podcast created to celebrate the launch of the Smithsonian Institute’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture: episodes are structured around objects donated to the museum to reflect different kinds of African-American experiences, with images of the objects shown on the web, their stories told through spoken word, and the objects themselves physically on display at the museum.

Most forms of transmedia are structured through a process of world-building. The concept of world-building emerged from fantasy and science fiction but has also been applied to documentary or historical fiction. Worlds are systems with many moving parts (in terms of characters, institutions, locations) that can generate multiple stories with multiple protagonists that are connected to each other through their underlying structures. Part of what drives transmedia consumption is the desire to dig deeper into these worlds, to trace their backstories and understand their underlying systems. Fictional texts imagine and design new worlds; documentaries investigate and map existing worlds.

A focus on world-building allows documentary producers to share more of what they learned, to encourage their viewers to develop a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the institutions being explored, the factors that impacted their characters’ lives, and the roots and potential responses to the problems being identified. Some use transmedia to explore multiple points of view or competing realities, which the engaged viewer is encouraged to bring into conversation with each other. A focus on documenting worlds may also allow professionally constructed texts to incorporate various forms of crowdsourcing and participatory storytelling, as the public shares their own experiences with the issue. Transmedia texts in all forms are layered: each extension adds something we did not know before and thus deepens our emotional connection to the material.

In my own recent writings, I talk about transmedia locations and logics.

Location refers to the context from which transmedia products emerge, so that the struggle of indie media producers in Manhattan to find a business model to sustain alternative reality games, often in collaboration with the advertising, publishing, or recording industries looks different from, say, the transmedia strategies currently shaping Hollywood franchises, such as the extended universes of Marvel, Star Wars, Harry Potter, or Avatar. And these look different from locations where transmedia production is state-subsidized to promote multiculturalism, education, or social change, all goals that dominate in countries where media production is shaped by public service priorities.

Brian Clark started us down this path with his East Coast and West Coast distinctions: “Neither is wrong. Few practitioners or creators work exclusively in one sphere or the other. One is not more noble or pure or profitable than the other.” We now can locate more models for transmedia as we start to look at exemplars beyond the United States.

By transmedia logics, I mean the different kinds of goals that transmedia producers pursue: early work centered on transmedia characters, stories, performances, and promotion, but more and more interest surrounds transmedia documentary, learning/education, mobilization/activism, diplomacy, and so forth.

As transmedia models are taking root around the world, we are seeing these different logics get mixed and matched: the Hollywood model involved the blurring of lines between storytelling and promotion/branding, with extensions building audience engagement around the so-called “mothership.” But an entertainment-education model, such as Hulu’s East Los High, sees the entertainment as creating a context for discussion of pressing social issues, with audience interests deepened through documentary or public service extensions and directed towards social change campaigns.

Transmedia was not a paradigm or a movement, but rather a provocation — a recognition of the increasingly networked relationship between different media sectors and platforms and in particular, a particular model of media audiences which valued tracking down and discussing scattered bits of information. These insights led to various experiments in what transmedia experiences might be like, some of which have taken deep roots, others (such as ARGS or hopefully, Second Screen) have proven short-lived.

I prefer a looser definition, one elastic enough to encompass new and emerging experiments. But then, I am an academic and my job is to generate discussion. If I were an industry insider, I might want greater exclusivity in order to enhance the market value of my particular skill set.

Given this history, we should not be surprised that individual creators, even those who have deeply invested in particular models, will migrate into other media sectors and adopt new models, bringing insights with them. This is what Phillips calls the “transmedia diaspora.” Otherwise, things would have become very static. That said, the discussions around transmedia are continuing to expand, bringing new people to the table.

First, the initial claims that transmedia was emerging from a particular moment, at the place where old and new media collide, has given way to a recognition that transmedia has a much longer history. Just as there are multiple transmedia locations and logics today, there is a rich history of people trying to tell stories by tapping the affordances of multiple media.

Watch for Matthew Freeman’s upcoming book, Historicising Transmedia Storytelling, which considers early 20th century examples such as the Wizard of Oz, Tarzan, and Superman, each of which were built up over time across multiple media experiences.

Transmedia has also slowly but decisively spread to media industries and creative communities around the world, each adapting what it means to the particulars of local production — from Japanese media mix to Bollywood and Nollywood, from the European Union to Latin America.

We might, for example, think about the kinds of transmedia interventions represented by Priya’s Shakti, a creative collaboration that uses graphic novels, games, and augmented reality, not to mention street art, to call attention to the struggles women face in India, a project which owes much to the spirit of the ARG experimenters Phillips discusses; or Burka Avenger, an animated series in Pakistan in support of women’s education, that owes more to the Sesame Street model. Or Istanbul’s Museum of Innocence, a location-based experience adapted to enshrine everyday objects referenced in Nobel Prize Winning novelist Orhan Pamuk’s novel about a doomed love affair.

And third, the concept of transmedia has caught the imagination of educators, activists, nonprofits, NGOs, journalists, and documentary producers, anyone who is struggling to get the attention and deepen the engagement of a particular constituency. Some of these projects are hyperlocal — see, for example, various efforts by educators to build augmented reality games that are tied to the specific communities where they are situated and encourage their students to do research as they contribute to the design and deployment of these projects. Here, transmedia connects with a new educational emphasis on multimodal learning or on models of multiple intelligences, both of which stress the need to communicate ideas through multiple modes of representation to stimulate the interests of diverse learners.

This doesn’t mean transmedia means everything to all people and thus means nothing to anyone. Rather, it means we need to be precise about what forms of transmedia we are discussing and what claims we are making about them. Phillips gives us a rich progress report on one important dimension of transmedia, but doesn’t provide a map of the whole terrain. Transmedia — broadly defined — continues to grow in many different directions as people respond to the challenge and opportunities of communicating systematically across multiple platforms.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.