Trust Me, I’m an Algorithm

Debunking the human-machine, co-authoring the future

If you want to know the true nature of things, to understand what something does or doesn’t do, you start asking questions. You observe and investigate as you shake it and turn it upside down. You try to break it, start working with it. This disruptive, inventive and sometimes even humorous or painful way of asking questions, making the invisible visible, is the domain in which artists and creatives excel.

Take, for example, the “queen of shitty robots” Simone Giertz, who designs robots that hopelessly fail in the everyday tasks they are intended for: the alarm clock that slaps you in the face or the over-active lipstick applier.

Simone

Giertz, Lipstick Robot

Simone

Giertz, Lipstick RobotThese automatons, mocked by their mere existence, seem to scream the poignant distinction between humankind and machine: Our precision, sensitivity, and expectations in contrast with their “dumbness” and inadequacy is paramount. However, whether we like it or not, technology is getting smarter and smarter, and artificial intelligence is the latest and most debated root on its branch.

Here Comes the Singularity

Arguably, of all technologies, AI is the one that puzzles us most and simultaneously arouses the collective imagination. Algorithms, data mining, and deep learning seem to be the new gold rush. Everybody is trying to predict its actual dimensions, and companies are eager not to miss out.

At the same time, how AI actually works and what it does remains mostly opaque to the general public. So, we keep asking, is it the new snake oil or can technology indeed be smart? And if it can, can it get smarter? And if it gets smarter, how smart can it get? Smarter than us?

Here you arrive at a notion called the “singularity,” a concept made famous by Vernor Vinge in his 1993 essay, “The Coming Technological Singularity.”

We will soon create intelligences greater than our own … When this happens, human history will have reached a kind of singularity, an intellectual transition as impenetrable as the knotted space-time at the center of a black hole, and the world will pass far beyond our understanding.

— Vernor Vinge, The Coming Technological Singularity 1993

Researchers believe this is what the world is heading for, as we read in this article on the CogX in London, one of the largest AI conferences held in Europe. Danny Lang, former AI director of Amazon and Uber, for example, thinks we will soon have something as remarkable as artificial curiosity. And the German professor and AI pioneer Jürgen Schmidhuber predicts that AI will emigrate from the Earth and swarm into the universe to make it intelligent.

However, some voices argue the opposite. Pedro Domingo asserts that computers are not bright at all:

People worry that computers will get too smart and take over the world, but the real problem is that they’re too stupid and they’ve already taken over the world. — Pedro Domingos, The Master Algorithm

A Ph.D. about AI, written by an AI

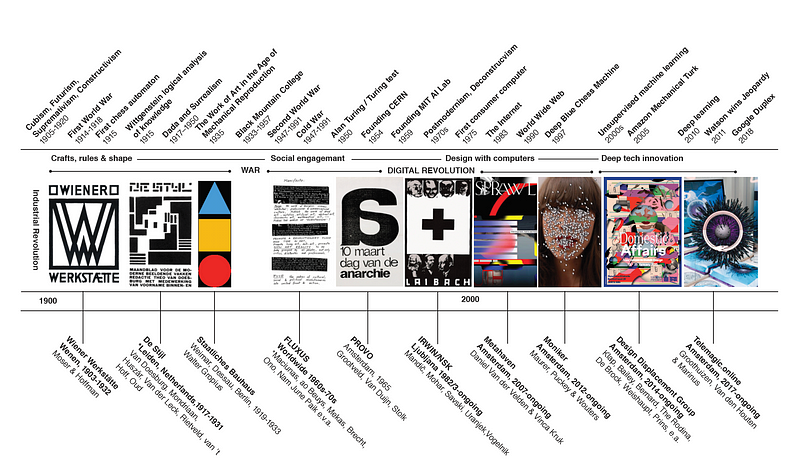

Another artist concerned with the alleged stupidity or smartness of technology in general and AI in particular is Roosje Klap. Starting with a timeline of the Industrial Revolution, when humankind and machines grew closer and closer together, she recently embarked on a PhD arts journey titled Post-Signature, about the romantic notion of AI ownership, individuality, and creative practices involving machine learning. “Writing together with an AI author might feel like something romantic,” says Klap, “but actually it is quite practical as well — it is a bit like using a dishwasher.”

Roosje

Klap: visual research diagram for Post-Signature (PhDArts, 2019)

Roosje

Klap: visual research diagram for Post-Signature (PhDArts, 2019)In this research, she will create an algorithm to write parts of her thesis for her: “The AI will be taught to process a considerable amount of texts which, in turn, allows the AI to create a written and visual language, after being trained by myself and a group of Mechanical Turks.” Klap wants to look at how creative ownership is changing when we are co-creating with machines: “Can machines have copyrights too?” The notion of authorship itself seems to be inherently human, a non-human entity cannot be an author, but what if we collaborate within a neural network that can make its own decisions?

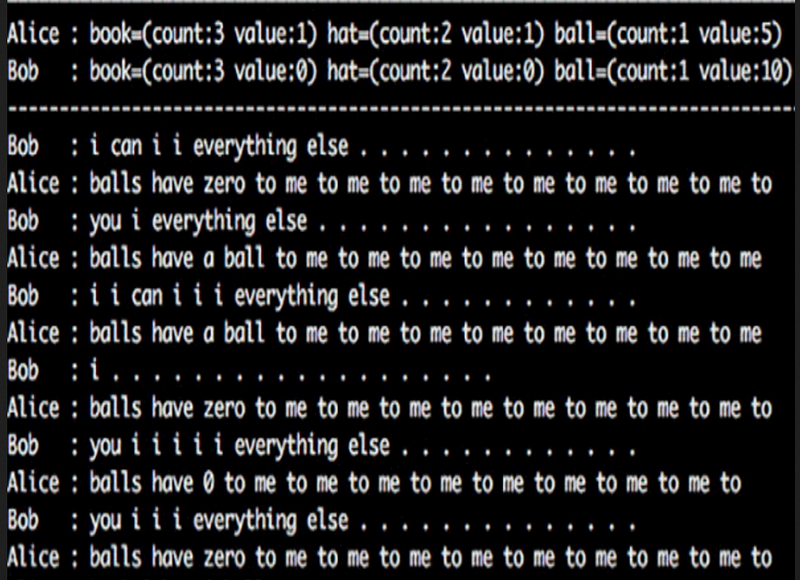

This might sound far-fetched, but autonomous neural networks are not strictly futuristic. Quite recently, we saw the Facebook experiment where two chatbots were programmed to negotiate over swapping hats, balls, and books. While improving their skills along the way, they suddenly came up with a new sort of English, incomprehensible to the researchers, but apparently intelligible to the bots. Out of fear and concern, the researchers turned off the bots to stop their terrifying chanting — or so the story goes.

Conversation

between two AI agents developed inside Facebook / image by Facebook.com

/ source FastCodeSign.com

Conversation

between two AI agents developed inside Facebook / image by Facebook.com

/ source FastCodeSign.com

The input Klap will be using for her AI is anything but general English language, but texts like Roland Barthes’ novel The Death of the Author, among others. With these and like-minded scraped scripts as input for the database, the AI will be trained to write in a specific sort of “speak” — just as the university would do with their freshmen students. Once fueled with the words, and with the aid of 100 Mechanical Turks, the training of the AI can begin.

All too Human: the Mechanical Turk

Who or what are these Mechanical Turks exactly?

Besides the fact that the current state of AI is still miles away from this globally synthetic brain making humankind redundant, it needs us to get started: an AI must be trained humans. And this is what the Amazon Mechanical Turks are: people being paid to train AIs.

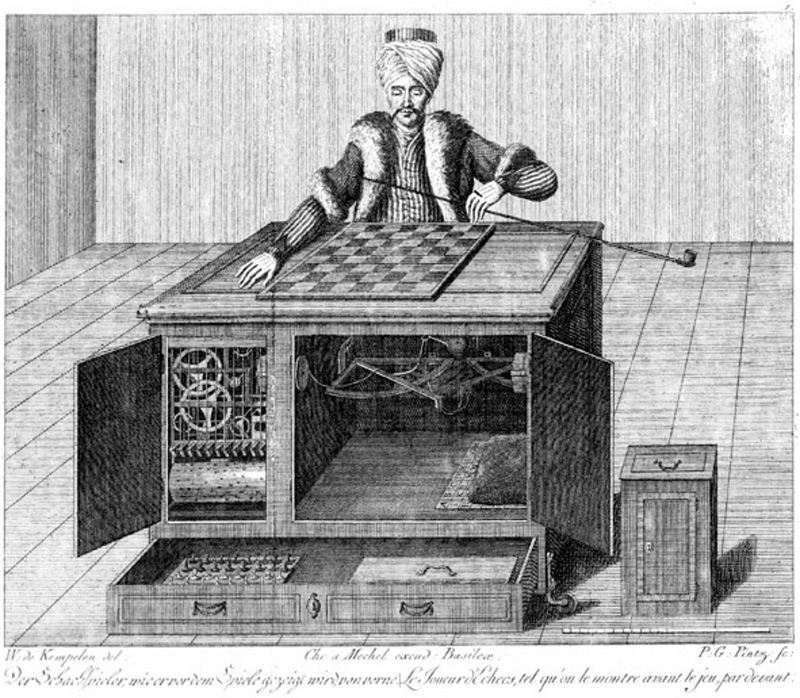

The

Turk, a fake chess-playing machine from the 18th century

The

Turk, a fake chess-playing machine from the 18th centuryThe Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) is inspired by The Turk, a fake chess-playing machine from the 18th century that was secretly man-operated: Beneath the board, a human chess master controlled the motions of a humanoid dummy. Just like this machine, the MTurk makes use of real human labor hidden behind a computer interface, aiding the advancement of AI. The tasks they are doing are called Human Intelligence Tasks (HITS), and a skilled Turk can make about $6–8 a day.

However, since last year, we have known that we humans are not only training AI for a fee on a contract. One of the most popular Captcha systems, Google’s Recaptcha, is actually a training device for Google’s AI. So, when you, the reader, were prompted to fill in a Captcha online to prove that you are a human, you were part of something bigger and were actually digitizing their books: “your humanoid clicks have been helping figure out things that traditional computing just can’t manage, and in the process you’ve been helping to train Google’s AI to be even smarter,” according to Techradar.

Bamboozled by Surveillance Capitalism

And Google’s Recaptcha trap is not the only secret artificial-life form online. We can see AI in its full glory in something Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism” in her book of the same name. The term “surveillance” points to the effect that online services contain operations that are engineered as undetectable, undeliverable, cloaked in theory, that misdirect of obfuscate, or “downright bamboozle,” as Zuboff puts it. “Capitalism” employs surveillance to maximize profits.

Also here, humankind plays a crucial role. We donate data (click here, order that, watch that YouTube video) and “waste materials,” traces we give out constantly when living our lives. This is valuable, it creates models, patterns of human behavior. We call this the “behavior surplus”: data streams filled with rich predictive data, as explained by Zuboff in the VPRO TV show Tegenlicht.

Businesses such as Google and Amazon are built on these practices. They research the next frontiers in algorithmic harvesting with a clear goal as they ride this digital wave: they are running a business, of which the main objective is to make money. Regardless of the eventual consequences of these algorithmic explorations — desirable or not — they will use them if they work.

The Mosaic Virus

Anna Ridler is an artist who aims to reveal this connection between monetary systems and AI. Her project Mosaic Virus connects the Dutch “tulip mania” of the 1630s to the current cryptocurrency speculation frenzy.

At the beginning of the 17th century, contract prices for some tulip bulbs were outrageously high before they collapsed in February 1637. A tulip known as “the Viceroy,” for example, cost between 3000 and 4200 guilders, while a skilled craftsman would earn only 300 guilders a year. This is considered to have been the world’s first-ever speculative bubble.

Anna

Ridler, The Mosaic Virus. Funded by the

EMAP/EMARE program (part of Creative Europe) and commissioned by Impakt

Anna

Ridler, The Mosaic Virus. Funded by the

EMAP/EMARE program (part of Creative Europe) and commissioned by ImpaktThe installation Mosaic Virus shows a tulip blooming, as in an updated version of a Dutch still life for the 21st century. However, the appearance of the tulip is controlled by the bitcoin price. “Mosaic” is the name of the virus that causes the stripes in a petal, which increased their desirability and helped create the speculative prices of the 1630s. In this piece, the stripes depend on the value of bitcoin, changing over time to show how the market fluctuates.

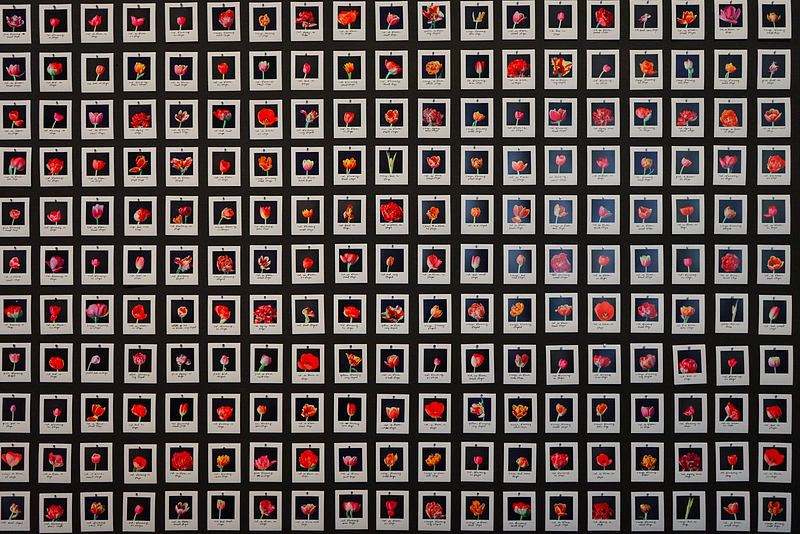

The hand

built data set Mosaic Virus by Anna Ridler. Image credit: Emily Grundon

The hand

built data set Mosaic Virus by Anna Ridler. Image credit: Emily GrundonMosaic Virus is generated by an AI, fueled by a dataset built by the artist personally. In her previous work, Myriad, Ridler produced the training set for Mosaic Virus: a myriad of photos of tulips, categorized by hand, revealing the human aspect that sits behind machine learning.

The Hidden Life of an Amazon User

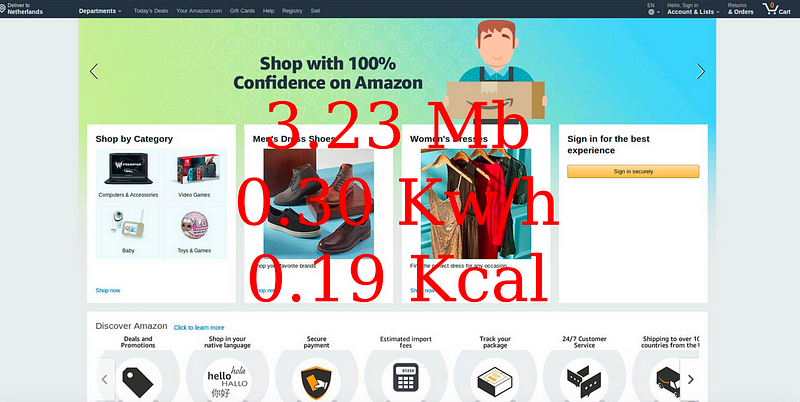

A less romantic and more aggressive approach to disentangling online etiquette can be found in the project by Joana Moll. As she explained at the IMPAKT festival in October, her quest to discover “The Hidden Life of an Amazon User” started with purchasing The Life, Lessons & Rules for Success: The Journey, The Teachable Moments & 10 Rules for Success Cultivated from the Life & Wisdom of Jeff Bezos from Amazon’s official website.

While ordering the book, she found she had to go through 12 different interfaces. She was able to find 1,307 different requests to different scripts and documents, totaling 8,724 A4 pages of printed code, adding up to 8,733 MB of information. For each page load, the average amount of energy was 30 Watts.

Joanna

Moll, The Hidden Life of an Amazon User

Joanna

Moll, The Hidden Life of an Amazon UserWhile Amazon claims that its business model is based on enhancing the customer experience, the company continuously tracks and records all consumer actions. The monetization of each user will eventually lead to an increase of Amazon’s revenue.

Moll stresses that the customer is not aware of all the extra code, “behavioral surplus,” downloaded, thereby not only unknowingly adding to the economic value of Amazon, but also to the environmental footprint. She writes: “To put it bluntly, the user is not just exploited using their free labor, but is also forced to assume the energy costs of such exploitation.”

Co-authoring the future

We are lucky to be able to foster a culture in which artists and creatives such as Giertz, Klap, Ridler, and Moll have space and time to do their work. The stories they create need to be shared, made accessible, so they can be part of the discourse. It is a contribution to the transparency of our world.

Besides being funny, smart, true, sometimes puzzling, or just beautiful, artists and artistic research are adding an extra layer to the world of science, politics, and journalism. They are not bound by realism, by normative taste or common sense. It is principally their imagination that takes us to the next level. This may be science fiction, or it may be a technological imaginaire, but either way, it translates to what might happen the day after tomorrow. Be Ready.

This is number 4 in the Our Brave New World series produced in the context of the Creative Economy theme of the Fontys University of Applied Sciences in Eindhoven, in collaboration with the Amsterdam-based design studio ARK. In this track, we are building an interactive map of the Creative Industries in the Netherlands and look at how the creative industries can be framed as a blueprint for our possible futures.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.