Nancy Baker

Cahill’s Margin of Error, Augmented Reality drawing, 2019. Location: Salton Sea State Recreation

Visitor Center (for Desert X)

Nancy Baker

Cahill’s Margin of Error, Augmented Reality drawing, 2019. Location: Salton Sea State Recreation

Visitor Center (for Desert X)VR and AR are opening up new paths for makers and museums

For arts institutions, the quest to engage new patrons is a never-ending one.

Each generation brings new expectations of how the world is supposed to “just work,” shaped by the technologies they have grown up with, along with a desire for the new and novel that emerging technologies can sometimes provide.

Enter stage right immersive technology — virtual, augmented, and mixed reality — with the tantalizing promise of being the “next big thing.” While fits and starts in the consumer adoption of these tools have turned the gadget-obsessed tech press from bullish to bearish, the actual potential of immersive tech as a medium has only begun to be unlocked.

Both established and emerging cultural institutions are turning to design techniques which leverage these technologies — mixing them with tried-and-true theatrical, architectural, and even retail design principles — to create transformative experiences for patrons.

Carne Y Arena, which won a special Academy Award in 2017 after a tour that included stops in Cannes and Los Angeles, leveraged both VR and physical immersive design to bring attendees into a re-creation of a migrant border crossing in the American Southwest. Cutting-edge VR was used to deliver the primary experience, but the large-scale set framed the story in a way that brought patrons closer to the visceral details that defined the reality for those who lived it.

CARNE y

ARENA, 2017. A user in the experience. Promotional image. Photo credit: Emmanuel Lubezki

CARNE y

ARENA, 2017. A user in the experience. Promotional image. Photo credit: Emmanuel Lubezki

Attendees of Carne Y Arena began their journey in a re-creation of a “cooler” — the extremely low-temperature rooms that undocumented migrants are often held in by Border Patrol. There they took off their shoes, placed them in a locker on the wall, and waited for a red light to signal that they could pass through an austere metal door. Beyond the door was a large, dimly lit sandbox with a looming border fence. This image was made all the more striking by the coldness of the sand squishing between toes clad only in nylon booties. Every step of this process happened before participants were helped into a mobile VR rig by two attendants, making the immersive tech only part of the immersive experience.

Large-scale installations like Carne Y Arena grab headlines and awards, but they’re not the only way that arts institutions can engage with the emerging art forms, as Kellian Adams Pletcher of experience design company Green Door Labs in Boston points out.

“There are a lot of ways to build immersive tech or experiences with whatever you have,” said Pletcher, “It’s just a matter of using your resources and adjusting expectations. Museums can do weird things. They can experiment. People donate things like time and resources to museums so… if [museums] are willing to be a little daring they could probably get a lot more than they think for their money.”

Pletcher’s firm works with museums and educational institutions to craft interactive experiences for patrons. The technologies she employs aren’t always of the headline-grabbing variety, taking advantage of what her clients have available. “Usually the most useful things museums will have is a good wifi connection and a bunch of iPads, which is pretty handy,” she said.

Yet the point of leveraging technology is to create a great experience for patrons, not just run down a checklist of the latest gadgets. For Pletcher the key is deploying the technology in context.

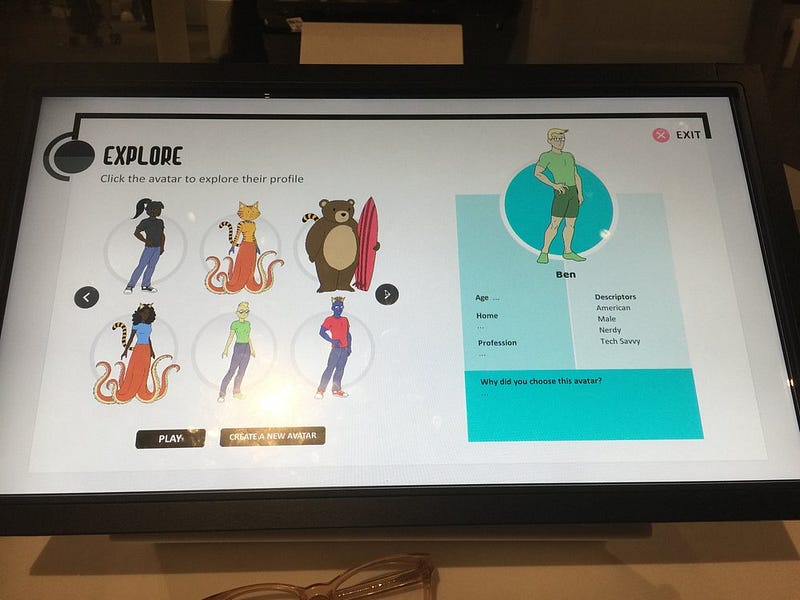

AVATAR,

In-Gallery Game at the Peabody Essex Museum’s Playtime Exhibit, February 2018 (Source: Green

Door Labs)

AVATAR,

In-Gallery Game at the Peabody Essex Museum’s Playtime Exhibit, February 2018 (Source: Green

Door Labs)“When I did Mustaches and Mayhem at the Smithsonian Castle, we used a really simple text-based mobile web program to get people through the story and puzzles hidden throughout the castle. This made things much more flexible, and tech works as a nice lock so you don’t have to use a million padlocks. Sometimes institutions will pull me on to build a custom digital experience. The Peabody Essex Museum asked us to make an ‘avatar guesser.’ ” This was a touchscreen game that dove into the relationship between online profiles and real-world identities. Pletcher said that when her clients “want an interactive experience I almost always just use off-the-shelf-programs and integrate it with real-space design.”

Sometimes the most immersive way to deploy technology is to hide it away where no one can see it. When done properly, the effects can be magical. This can be seen at popular escape rooms like New Orleans’ Escape My Room. DeLaporte Ventures, the company behind Escape My Room, recently opened an attraction for the Audubon Aquarium of the Americas called Escape Extinction: Sharks, which mixes escape room puzzles, actors, and exhibit design to provide an engaging and educational experience.

“Often we try to stay away from front-facing technology,” said DeLaporte’s founder Andrew Preeble, who doesn’t “like to use screens unless they are a stand-in for something which we otherwise wouldn’t be able to do.”

As in theme park design, the goal isn’t to sell people on the value of the technology, but to use the technology to give them the best experience possible. In these cases a little slight of hand assisted by existing technology can go a long way. Yet sometimes experience designers want to jump straight into the latest and greatest technology, or maybe just want to take advantage of the fact that people are always on their phones anyway, so why not meet them where they already are?

A screenshot

from Meow Wolf’s Anomaly Tracker

A screenshot

from Meow Wolf’s Anomaly TrackerSanta Fe’s Meow Wolf, which has turned the art world on its ear with its immersive art installations, doesn’t shy away from the cutting edge of mixed reality tech. An app — the Anomaly Tracker — adds another layer to the already rich House of Eternal Return. The free phone app lets visitors tune into augmented reality extensions of installations inside the home, playing into the multiversal mythology the collective has built for their work.

In a similar vein, Disney’s Play app adds a layer of game interaction to their theme parks, a feature which has been put front-and-center in the Star Wars themed expansion that opened at Disneyland and will soon be at Walt Disney World. Both apps take advantage of the social norms around phone usage, and the ways in which audiences — particularly younger audiences — have been conditioned by games such as Pokemon Go, which drape a digital narrative layer on top of the physical world.

Yet you don’t have to be a multi-billion dollar corporation, or an arts collective rapidly expanding into multiple regions, in order to create an app.

Visual artist Nancy Baker Cahill has an app of her own, 4th Wall, which she uses to deploy AR versions of her work at venues around the world. Cahill’s visual work has long featured vortexes — swirling masses of force constructed out of fragmentary strokes. In mixed reality the pieces reach titanic proportions, with the AR versions often hovering in the sky over the scene as if they were supernaturally charged storms. “I feel I am reaching a broader audience, and one that wouldn’t traditionally self-identify as being art-enthusiastic,” said Cahill. The app, she told us, has opened up new possibilities for her work.

Margin of

Error, Image of 4th Wall App, 2019, Salton Sea, CA; photo by Lance Gerber

Margin of

Error, Image of 4th Wall App, 2019, Salton Sea, CA; photo by Lance Gerber“It’s been very liberating for me in terms of being able to act swiftly and nimbly, not waiting for ‘permission to do certain things, and to reach out directly to and collaborate with other artists I respect. It is, though, by its nature, inviting audience engagement outside the walls of traditional institutions by inviting viewers to specific sites, and also by putting the choice of where and how they experience art in their own hands.”

She’s also found herself in conversations with institutions interested in collaborating, “which I am open to, provided it looks outward versus in.”

While having an app isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution — indeed, Cahill points out that access to the technology is an issue that needs to be addressed, one that institutions could play a role in making more equitable — even the access and distribution problems can lead to positive experiences.

“There have also been magical moments where spontaneous bonds, connections, and conversations occur between and among strangers when one person does have access to the app and is willing to share it, or the experience of it, with the people around them. This is part of the unexpected magic of immersive tech and the audiences you could not possibly have imagined existing, fleeting as they may be.“

There are a number of roles that established institutions can play — from patron of the technologically enhanced arts to bridger of the digital divide — but the first one is always as connector to their communities, as Green Door Lab’s Pletcher argues.

“Sometimes I get the feeling that museums are like ‘If you build it, someone will come’ rather than saying ‘Amateur classical musicians, this is for you.’ ” Look at how many people go to (gaming convention) PAX East, but Boston museums don’t leverage that by building any PAX-related programming. There’s a lot of power in these little communities — I see a lot of unexplored opportunities. If they’d look at specific audience first and then built an immersive, interactive experience for them I think they’d get a really interesting response.”

Which brings us to the first — and last — principle of immersive design: know your audience, and know what relationship you’re looking to foster between them and the work. No matter the technology deployed, the principle remains.

Noah Nelson is the founder and publisher of No Proscenium: The Guide To Everything Immersive, a publication which covers the breadth of immersive art & entertainment.

This piece is part of an issue of Immerse sponsored by the Knight Foundation in conjunction with Knight’s call for ideas to advance immersive arts experiences. Open for applications through August 12, the call offers recipients a share of $750,000 in funding, as well as optional technical support from Microsoft. Learn more.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.