An interview with documentarian Deniz Tortum

The Virtual Production Bulletin is our new Q&A series about the intersection of game-engines, LED walls, real-time motion-capture, VFX and animation with documentary and non-fiction storytelling. It is co-produced with the Co-Creation Studio. How can we understand documentary techniques and ethics with new paradigms of virtual immediacy, abstraction or reenactment? What are the systems that enable and encourage such paradigms? And what other questions should we be asking about the blurring of virtual and physical space?

September 1955 (2016, with Cagri Hakan Zaman

& Nil Tuzcu),

installed at !f Istanbul 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

September 1955 (2016, with Cagri Hakan Zaman

& Nil Tuzcu),

installed at !f Istanbul 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.The Bosphorus Bridge, or 15 July Martyrs Bridge, is one of three suspension bridges in Istanbul that connects Europe and Asia. The bridge’s social, cultural and ecological histories form the foundation of a media project by Deniz Tortum, a film and immersive media practitioner who aims to use the technique of reenactment within a virtual production workflow. Tortum’s latest short film, Our Ark (co-directed with Kathryn Hamilton), recently premiered at IDFA (International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam). It documents the process of making 3D replicas of the natural world, thus commenting on realism and representation. At MIT, he co-teaches an interdisciplinary course titled “Immersive Media and Virtual Production” with Cagri Hakan Zaman, a lecturer and research leader of the Virtual Experience Design Lab.

In this interview, Tortum and I discuss the development of an emergent process and workflow from its earliest stages of ideation. How might collaborators develop an iterative project? Why would a documentary filmmaker choose virtual production? And how exactly do we define it here?

Tortum isn’t new to historical reenactment. In September 1955, a 2016 VR documentary on the Istanbul Pogrom, Tortum used sound, imagery and interactivity to simulate a photography studio under attack, offering the audience a relationship to both the moment in time and a place. Given that the processes around virtual production are still nascent, Tortum challenges the tendency to reflexively jump at the promise of technological tools, instead engaging in a more philosophical dialectic between object and medium or object as medium. His dialectic presents a blueprint that artists may use for their own development processes.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

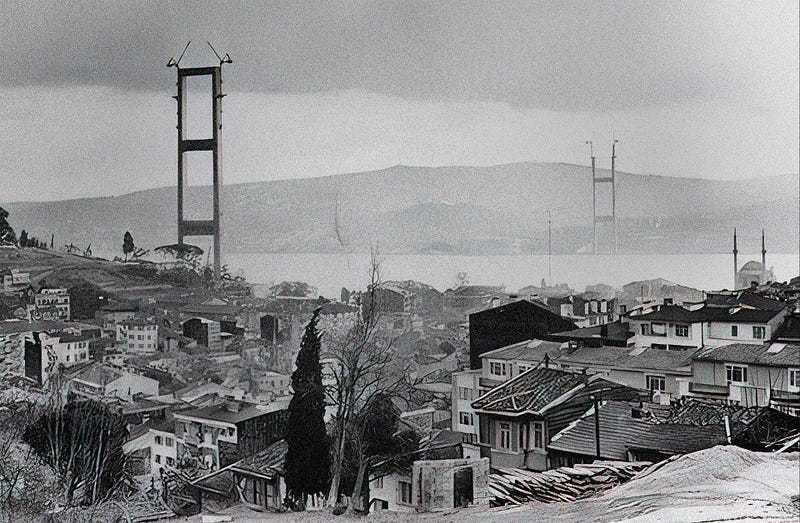

A found

photo of the Bosphorus Bridge under construction. Tortum’s project

Bridge

(Köprü) examines the period between 1970–1973

when the

construction of the first Bosphorus bridge took place. Image courtesy of the

artist.

A found

photo of the Bosphorus Bridge under construction. Tortum’s project

Bridge

(Köprü) examines the period between 1970–1973

when the

construction of the first Bosphorus bridge took place. Image courtesy of the

artist.Srushti Kamat: Do you know if you’ll call this Bosphorus Bridge project “fiction” or “documentary,” or will you determine that later?

Deniz Tortum: I know that I will be using archival footage. We [Ege Berensel and Efe Murad] collected several thousand reels of 8mm film from that era in Istanbul. The film will consist of archival footage and fictionalized reenactments. It will use 3D models and it will use game engines for part of the production. Thinking from the perspective of architecture — before the bridge was an actual bridge, it was a 3D model — not a computer model, but a physical model. And before that, it was a drawing. So these different levels of representation and how we manifest those representations to change reality and the physical world have parallels with virtual sets and 3D models of virtual production. Some of these are premature ideas that I can’t completely articulate.

A still from

Our Ark (2021, with Kathryn Hamilton), a short film essay that

questions massive

scanning projects to make 3D replicas of endangered animals, objects,

photographs, and more. Image

courtesy of the artist.

A still from

Our Ark (2021, with Kathryn Hamilton), a short film essay that

questions massive

scanning projects to make 3D replicas of endangered animals, objects,

photographs, and more. Image

courtesy of the artist.SK: With fiction, there is a certain assumption that all works will be pushing imaginative bounds. With documentary or, rather, with reenactment, there may be a responsibility or a weight to make these boundaries clear. How do you navigate that?

DT: What is a documentary? I think of any film that has its own claim to reality as a documentary. I don’t think there is necessarily an extra responsibility on documentary compared to fiction, but rather a difference in how you make your claim of reality. It’s more a question of method. I value the self-reflexive mode in documentaries, that hints at the production process. Within this self-reflexive mode, if you’re shooting a documentary on a virtual production set, are there ways to address the method of production? That’s a big question for me. What is the relationship between a virtual production set and the construction of a bridge? What is the relationship between the story of the film and shooting it on a virtual production set? I do sense that there are relations, but if I cannot articulate it in the end, I don’t think I would shoot on a virtual production set. For me, the method of production should somehow reflect what the film is about.

SK: Could you expand on the last part?

DT: In my work, the shooting method and the style generally change and react to the type of scenes, spaces, and relations in each scene. So the camera reacts to the things it is capturing, and the style is guided by the encounters. I’m thinking about how a virtual production set can be used not only to tell a story but also be a site of encounter between the film’s style, production method, and the content in how it reacts to the story.

SK: I love the idea of linking the building of a bridge to the building of the set. It strikes me that rushing to define a virtual production process in a rigid manner might be about control. As you walk me through your thinking process, I’m noticing that there also needs to be fluidity and abstraction in the iterative space.

DT: You need to stay with uncertainty a bit for your ideas to grow and develop. Real-time game engines give a lot of freedom and a lot of reversibility during the shooting process. If you want, you can shoot during a virtual golden hour for hours. It takes away the tension of shooting in the physical world, the accidents, and the imposing presence of physical laws. But it also brings in something new. For example, you can suddenly turn a realistic rendering into a wire-frame rendering and then see how the actors will react or how it will change their improvisation. Or you can change the scene to something abstract while your actors are in the scene. It is almost like you can immerse your subjects in a virtual montage.

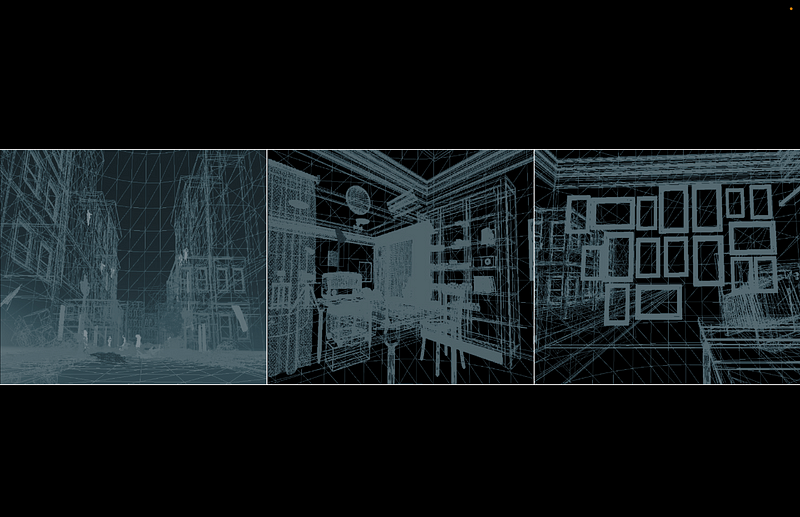

Wireframe

renderings of scenes from September 1955, modeled by Cagri

Hakan Zaman. Image

courtesy of the artist.

Wireframe

renderings of scenes from September 1955, modeled by Cagri

Hakan Zaman. Image

courtesy of the artist.SK: How do you make a case for virtual production at this early stage of the process, especially when it comes to expenses? You’ve worked in VR and with green screens. Are there transferable skills?

DT: One thing that virtual production allows that a green screen setup doesn’t is improvisation in virtual environments. Because both the crew and the actors are within the space, they can make decisions on the spot. I believe the most expensive thing in virtual production is the LED wall itself, but I hope within a year there will be more affordable studios.

SK: Is your main interest in virtual production that it produces heightened performance from actors or are there other factors to it?

DT: In VR, especially around 2015 and 2016, everyone was focusing on the viewer’s experience and how to design for a viewer. But virtual production removes the viewer and uses the same setup and same technology to do something completely different. The environment doesn’t change when the actor moves; the environment changes when the camera moves. There is a relationship between the camera and the environment. And it is modifiable. That was one of the inspiring things about virtual production to me.

A still from

Phases of Matter (2020), Tortum’s feature documentary that

follows living and

inanimate residents of a teaching hospital in Istanbul, moving from the

operating room to the

morgue, between life and other states, the real and the virtual. Image courtesy

of the

artist.

A still from

Phases of Matter (2020), Tortum’s feature documentary that

follows living and

inanimate residents of a teaching hospital in Istanbul, moving from the

operating room to the

morgue, between life and other states, the real and the virtual. Image courtesy

of the

artist.For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.