An interview with Philip Galler, Co-CEO of Lux Machina

The Virtual Production Bulletin is our new Q&A series about the intersection of game-engines, LED walls, real-time motion-capture, VFX and animation with documentary and non-fiction storytelling. It is co-produced with the Co-Creation Studio. How can we understand documentary techniques and ethics with new paradigms of virtual immediacy, abstraction or reenactment? What are the systems that enable and encourage such paradigms? And what other questions should we be asking about the blurring of virtual and physical space?

A virtual production set from

Solo: A Star Wars Story. Image courtesy of Lux Machina

A virtual production set from

Solo: A Star Wars Story. Image courtesy of Lux Machina

Though virtual production is an umbrella term that includes many technologies like motion-capture and game engines, the LED screen is often framed as the indisputable star of the show, functioning as a visual icon of change, or in some cases, a paradigm-shifter. On production sets, the crew and employees focus on how to deploy and utilize them. But the LED screen, alongside other infrastructural objects like cables, satellites and their interconnected systems, influence the entire ecosystem of new media—which is why scholars like Lisa Parks persuasively argue for studying their dispositions and the people who maintain them. Focusing this interview on the LED screen is a chance to apply an infrastructural approach to a workflow in nascent development.

Philip Galler is Co-CEO of Lux Machina, a company specializing in virtual production. Lux Machina’s team has been at the forefront of building the technology that initiated popular discourse around virtual production. Their impressive portfolio includes TV series like The Mandalorian on Disney+, movies like Red Notice on Netflix, and live events like the Academy Awards, to name just a few.

The following interview, conducted in October 2021, has been edited for length and clarity.

Srushti Kamat: Could you tell me more about the technology behind the LED screen?

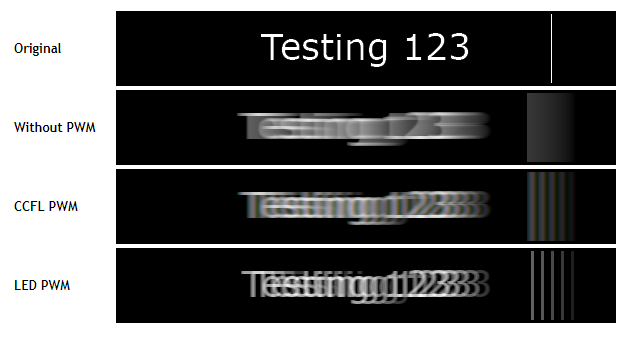

Philip Galler: Roughly 90% of all LED technology is a pulse-width-modulation-driven technology, which means there’s a period of “on” and a period of “off” that dictate brightness. Because of the perception of motion, when it sees something called the PWM flicker, the human eye interprets a cohesive signal.

PWM flicker

types. Image courtesy of Iris Tech

PWM flicker

types. Image courtesy of Iris Tech

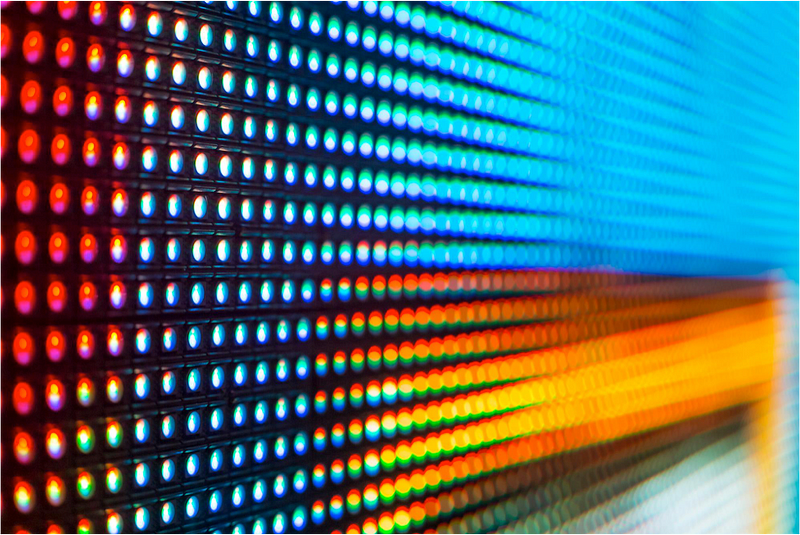

Scientifically, LEDs (Light-emitting-diodes) are terrible. They’re not a black body source. So, ultimately, you’re not getting a wide spectrum of color. You’re getting very narrow valleys and peaks in the red, green, and blue. Perceptually, that builds the wavelength of color that we see across the full spectrum of visible light. It was never intended as a display device. That is one of the biggest challenges and it’s where the most science happens for people like us. How do we align that light source with cameras, which fundamentally are also terrible at seeing color?

A close-up

of an LED wall. Image Courtesy of Matrix

Visual

A close-up

of an LED wall. Image Courtesy of Matrix

VisualIf I have an LED that flickers 300 times a second and it’s on half the time and off half the time, it’ll look like it’s at half the brightness. This is a fundamental digital signal mechanism. We build as many LEDs as we possibly can because we’re trying to design a PWM-based system with harmonious colors.

SK: Are you in collaboration with lighting directors, then?

PG: We definitely have conversations ahead of time about collaborative lighting or what we call interactive lighting, which is lighting that gets played back interactively from screen. It provides a sense of immersion for talent. You’ve also got to get production costs, makeup, hair, the camera crew, the visual effects and virtual production teams equally aligned.

SK: Do you think it’s the science that should come first or the story and then the science can catch up to it?

PG: Both. I want people to come up with the stories that they want to tell, and I want to find ways for technology to be able to empower them to tell those stories, whether that technology is available now or in a decade. And on the other hand, I want people to know that there are limitations because technology isn’t a perfect thing. Once it’s deployed, we need to find ways to compromise with the art. If we get someone 90% of the way there with technology, I want the other 10% of the way to be something that they’re willing to look at and go, “You know what? It’s not perfect for right now, but it’s perfect for this.” It shouldn’t be that we’re setting up LED walls, projection and light field displays when we’re also sitting there going, “This really doesn’t do what we needed to do.” When technology gets in the way of being able to tell the story that we’re trying to tell, we fail, because telling that story is the only reason we all have jobs. At the same time, some people will allow technology to be the roadblock so that they don’t have to be challenged.

SK: There’s a fine line between technology preventing us from telling the story we’re trying to tell, and technology being something that we’re refusing to accept.

PG: We’ve gone too far when we’re in a position where we can’t actually get technology to do the thing we want, but we’re still trying to get it to do the thing we want just to say that we did. This can be a big problem with filmmakers. Filmmakers are often trying to push the boundaries for no reason other than pushing the boundaries, and they don’t necessarily have a reason for doing so other than to be able to put out a press release saying that we did something. I think if they stepped back for a second and realized that they’re better off focusing on narrative creativity using the technology that currently exists, the people who are actually working on the technology could spend more time building the next thing that would enable them to tell a better series of stories next time.

A virtual

production set from Red Notice. Image courtesy of Lux Machina

A virtual

production set from Red Notice. Image courtesy of Lux Machina

SK: Where is Lux Machina’s place in all of it?

PG: It’s really hard to understand what we do until you’re on the inside. We’re not doing any cursory stuff. We’re not putting in forests downloaded off of the marketplace and hoping that it looks good. We’re fundamentally trying to understand how it’s lit. We’re trying to understand how it works. We’re trying to understand how we can make it better. And that’s a rabbit hole.

Behind the scenes. Image courtesy

of Lux Machina

Behind the scenes. Image courtesy

of Lux MachinaLots of schools teach you to do one thing. “You’re going to become a broadway lighting designer or you’re going to become a mechanical engineer or you’re going to focus on architecture,” they say. I’ve got a whole bunch of Imagineers who work for me who are hired to do one thing and then they’re doing something different. What they’re doing is what they actually love. It took them a decade of working at Disney to understand that it’s okay to go out of your comfort zone. It’s okay to reach across the aisle and go, “Hey, I want to learn that new thing that I find really fascinating even though I never thought I would,” or, “Hey, I want to learn that thing because it takes on a role in leadership, but I never thought I’d be able to.” From my perspective, it’s about empowering these people.

SK: Are you advocating for a more widespread understanding of computation and cross-discipline collaboration?

PG: I think communication is something that people in the arts industry tend to have an ego about. They tend to not be able to clearly communicate core concepts because they think, “Oh, I wrote it and so I own it.” Once you learn enough about code and computation you start to say, “I’m not going to write this library myself. I better go get somebody who sells the library because I’m not going to spend the next six weeks on it.” All of a sudden, you’re collaborating. “Oh, I need to talk to a writer? Okay, I should talk to a writer about concepts. I don’t own this entire thing? I own just this little bit of it.” That’s a really, really important thing to learn.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.