A maker discusses her work on life in isolation and connecting with others through technology

“Have a daily routine.” “Do your exercise.” “Study your space — examine the paint on the wall.”

The

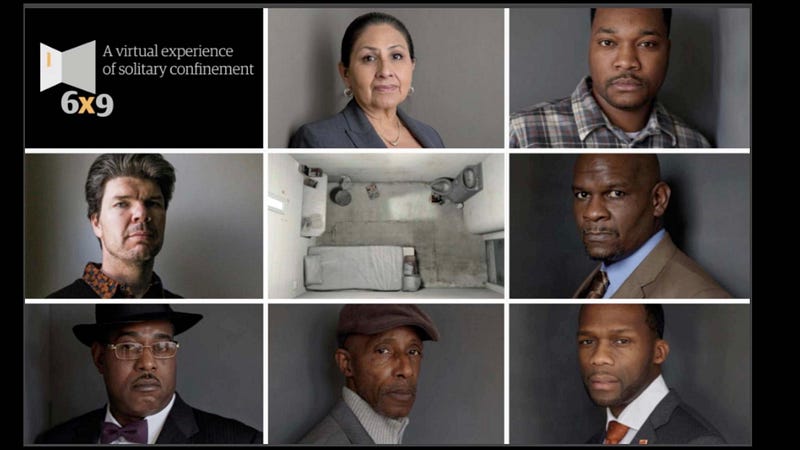

Guardian. 6x9: a Virtual Experience of Solitary Confinement

The

Guardian. 6x9: a Virtual Experience of Solitary ConfinementThis was some of the advice survivors of solitary confinement shared with my co-director Lindsay Poulton and I during interviews for the Guardian’s VR piece 6x9. We had asked them what helped them get through the years that they had all spent caged in six-foot by nine-foot cells for 23 hours a day. We wanted audience members to hear their voices as they sat in the headset in the computer-generated cell we had created with The Mill.

I’ve been reminded of their words the last few months as the faded blue walls of my living room have become all too familiar. And I’ve marveled at the discipline all 10 of the survivors managed as I hopelessly fail my exercise goals week after week and still haven’t managed to find a solid routine.

As we’re now too painfully aware, being in confinement has serious implications for mental health. 6x9 was a piece not only aimed to illustrate how small a six-by-nine-foot cell is but also to show the psychological effects of solitary confinement. Psychologists Craig Haney from the University of Santa Cruz and Terry Kupers at the University of Berkeley rattled off to me a litany of effects that sensory deprivation can cause: hallucinations, panic attacks, dizziness, perspiring hands, insomnia, obsessive thinking, paranoia, anger, nightmares, heart palpitations, and other physical and psychological problems.

Professor

Craig W Haney

Professor

Craig W HaneyIn 2016, as virtual reality was just taking off for its second wave, headsets felt like the perfect form for the story. Indeed, it was a story all about space and its effects on the human mind and soul. Now, the UN has recognised that solitary confinement is a form of torture.

The problem for us as directors was three-fold: first, for our audience, confinement wasn’t actually confined. We made it very clear to them for health and safety reasons that at any stage they could take the headset off. Second, we were immersing people for nine minutes, not the months, years, and even decades that those incarcerated can be put in “the box.” Third, how can you represent psychological impairment? Many of the effects like hallucinations that many of our collaborators in the piece described to us, Lindsay and I hadn’t experienced ourselves.

We were brutally aware of all these challenges as we made the piece. Some we tackled head-on. Five Omar Mualimm-ak told us a story of repeatedly seeing his mother in the corner of the room; when he turned his head to see her, she would disappear. This was something we could recreate in Unity. Blurred vision was another accomplishable technique. Blurring reality and the imagination was harder, as was uncontrollable anger.

We consulted Terry and Craig along with a local psychologist and sent images to Five and Johnny Perez (who had also experienced solitary confinement for 18 months) before showing it to them in person as we prepared for our launch at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Johnny Perez

and Five Omar Mualimm-ak checking the dimensions of the Tribeca Film Festival set. Photo Francesca

Panetta

Johnny Perez

and Five Omar Mualimm-ak checking the dimensions of the Tribeca Film Festival set. Photo Francesca

PanettaJohnny and Five spent part of the week with us at the festival, talking to audience members about the project and their real experiences in isolation. Johnny even persuaded Robert De Niro to watch the piece when he passed through Storyscapes. He was so taken by the piece he then went to talk about it on the Jimmy Fallon show.

The Guardian launched the piece for Cardboard and Gear VR and it toured a number of festivals. More importantly to us, it became a useful advocacy tool. Campaigners asked to use it to demonstrate to people what isolation feels like. And the piece went to the White House as part of the South by South Lawn interactive festival, bringing together art, ideas, and action for policymakers to see.

President Obama went on to make changes to the federal prison system, including banning solitary confinement for juvenile offenders and for prisoners who have committed low-level infractions. But four years after the release of 6x9, there are still at least 60,000 people currently in solitary confinement in the United States.

More recently, prisons have used solitary confinement to punish prisoners protesting conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, where cramped quarters and communal living in prisons are hot spots for the virus.

In Britain, confinement is being used in prisons to prevent the virus from spreading. Prisoners are kept in their cells for between 22 and 23.5 hours a day, with no visits allowed and education programmes paused.

Confinement in the time of Corona

My experience of confinement in London during lockdown has been nothing compared to the experience of those incarcerated. Nevertheless, it has been taking its toll. As someone usually busy travelling to conferences and festivals and who thrives on human interaction, I’ve had to try other methods to break myself out of my one-bedroom flat.

I acted as a tour guide around a virtual National Portrait Gallery to see the shortlisted prize winners. We were all on Zoom, but I screenshared and navigated us through the space as we all gave our inexpert commentary. I have a bizarre weekly cinema club where my friends sit silent on mute next to me while we watch films together and discuss them afterward. To be honest, it’s a poor substitute for real human life.

In Event of

Moon Disaster at Cannes XR 2020

In Event of

Moon Disaster at Cannes XR 2020In Event of Moon Disaster, which was conceived as a physical installation (premiering at IDFA last November), has been reimagined as a VR experience for Cannes XR. Walking around the Museum of Other Realities that hosts Cannes, I got a sense of how exciting a virtual festival could be: seeing others inside immersive experiences with you, opening up festivals to those unable to travel or afford passes.

Corona

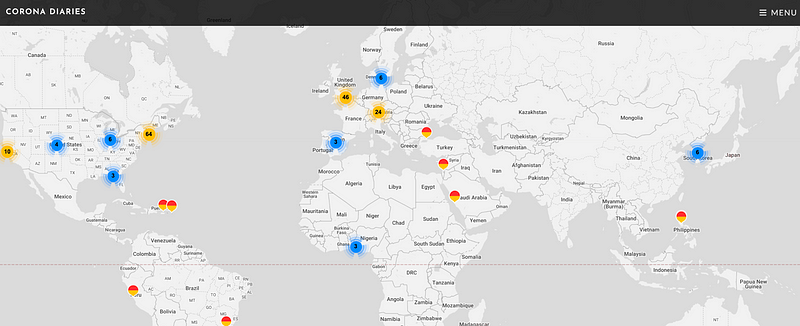

Diaries

Corona

DiariesI’ve also been thinking about simple ways to connect people through technology that don’t involve headache-inducing headsets. A group of journalists and artists colleagues of mine got together to create Corona Diaries to connect similar experiences around the world through audio. I’ve been making music with friends using Acapella and enjoying amazingly creative collaborative works on TikTok. My gut feeling is that hijacking, subverting, and adding on to some of these simpler platforms is the way forward rather than the immersive community building our own from scratch.

With that in mind, as I ruminate now in my much-larger-than-6x9 apartment, I wonder if I were to build this piece about solitary confinement again, how would I make it? VR I still feel is the most powerful medium for the story, but if I were to heed my own advice on simplicity, perhaps I would make it as an audio meditation — connecting the walls of our own rooms to the cells that hundreds of thousands of people in the world are confined in right now, still using the voices of Five, Johnny, and the others.

But I would ask the audience to relate their space and their own experiences to prisoners confined in cells for much longer periods. To consider how restrictions on being able to meet and interact with other human beings can impact your wellbeing. Finally, a small interaction, even if not in person, can mean so much in these times. So, the piece I would make now would end with a call to action to write to those in solitary confinement, an effort supported by the charity Solitary Watch.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.