Generating our climate futures

How do we visually communicate climate change? How do we balance speculation and realism to think through events that are dispersed around the world and projected to intensify in the future? I came across the AI-based climate change communication project This Climate Does Not Exist a few months ago, a project that proposes one answer to these questions. This Climate Does Not Exist attempts to tackle the cognitive biases we have against climate change like psychological distance, or the perception that climate crisis is an abstract phenomena that will happen sometime in the future. By personalizing and localizing the effects of climate change, the project hopes to overcome this cognitive bias and get people more engaged.

When you visit the website, the first thing you see are AI-generated images of the Arc de Triomphe on fire and the Kremlin Palace underwater. The welcoming text reads: “Can you imagine these kinds of disasters happening in your backyard?” To use the site, you pick a location anywhere in the world from a Google Map embedded in the website. You are encouraged to pick a place that carries an emotional meaning for you. Then, you select one of three impacts you are presented with: “flood, wildfire, or smog.”

The website finds the Google Street View image of the place you picked (if it is available). Then, using Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) algorithms, a machine-learning framework that can generate novel images through learning from existing image databases, it generates your preferred natural disaster at your preferred destination. For example, here is MIT’s Dome after selecting “fire”:

Even

threatened with fire, the Google Street View car is still on duty.

Even

threatened with fire, the Google Street View car is still on duty.And here is the same Dome, this time flooded:

The water not only washes away the Google Street View car but also the Google logo altogether; perhaps a more truthful representation of a climate crisis future?

In reality, measuring the impact of seeing these images on comprehension and any further action is challenging. (Yale’s Climate Change Communication program is a good resource for anyone interested in the topic.) How effective is This Climate Does Not Exist? Does seeing a picture of a familiar sight flooded actually change perceptions about the urgency or reality of climate change?

In order to communicate the climate crisis, what images do we need?

For one perspective, I talked to Toby Smith, who leads the Climate Visuals project. Climate Visuals is an “impact-oriented climate photography resource” that researches and curates the most effective images for climate change communication. They created a useful visual communication guide, “7 principles for visual climate change communication,” and they work with organizations such as The Guardian to better communicate the climate crisis.

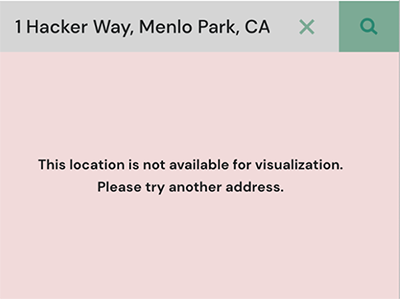

Smith remarked that This Climate Does Not Exist would be meaningful to the audience only in relation to places they live and frequent. “Your house needs to exist in Google Street View,” Smith remarked, especially given that many places in the world are still not accessible, contrary to the seeming ubiquity of the project’s reach. They are either overlooked by Google (e.g. I couldn’t get images of my childhood neighborhood in Istanbul, as Google doesn’t photograph many parts of the world) or protected by legislative walls (e.g. Meta headquarters). In this way, the AI project echoes some of the problems we do know about the impact of climate change; that many places will be neglected when they’re flooded, and some will be protected from it.

“For an image to be successful, it needs to be perceived to be authentic; to have happened; to have real people.” says Smith. With this guiding principle of the Climate Visuals project, AI-generated images are speculative disasters. According to Smith, seeing an artificially generated future undermines the images’ authenticity and power: they might be less emotionally engaging than the photos that show real floods. Trust is an important factor and lack of it might lead to climate skepticism, and the ability of GANs to create realistic images (sometimes referred to as “deepfakes”) and thus undermine images as a source of truth has already been the subject of much trepidation and discussion.

Yet there is one issue: how do we communicate a climate future that hasn’t happened yet? The use of GANs attempts to bridge this gap by generating imagery. These images are generated using already existing image databases. They create a future using the past data; they show what we already know. However, the future does not mirror the past.

The worst impacts of the climate crisis exist mostly as computer simulations. This is a major issue in climate change communication. These projections are not images but rather numbers, and statistics, which can be ineffective for many people. These statistics then need to be interpreted and communicated. Disaster images created by AI are one way to circumvent this, however they are not able to predict the complexity of the future. With each passing month, an unimagined climate-future becomes real. For example, last month, the heat wave affecting India and Pakistan led to eagles falling from the sky due to dehydration. The real world continues reinventing itself.

My own most powerful experiences and engagement with climate change have not been through images, they have been through reading. I keep thinking about the horror of the massive heatwave in Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry of Future, the pervasive anxiety in Jenny Offill’s Weather, or the worst-case realism of Roy Scranton’s Learning to Die in the Anthropocene. These are works that communicate the ambiguity of the future. Climate change is not an issue anymore, it is a paradigm we live in. Non-visual work might have an advantage on this front to figure out the conditions of this paradigm and portray an unknown future because it doesn’t collapse the process into a single moment.

It doesn’t help us too much to reduce the future climate crisis to a flooded or burning city. The end result is not what is scary. What is scary is the in between, as we anticipate the future and move towards it. How do we initiate the hard conversations about mass migrations, societal organization, ethics and values for a tomorrow that might be worse than today? This Climate Does Not Exist personalizes a rather sterile disaster-future but doesn’t answer the question: What climate will exist?

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.