Who Is VR For?

New

Dimensions VR Lab artists in July 2017

New

Dimensions VR Lab artists in July 2017What are the models we could set up to build a more inclusive group of artists and field builders working in the creative virtual reality space? Over the summer, I’ve been interviewing makers and practitioners about this question.

Full transparency: I produce Immerse and work closely on each issue. Writing this feels a bit like insider trading and I have also taken the liberty of talking to many people on the Immerse editorial board for this piece.

Immerse is just one thing I do, however—I have a lot of skin in this game. I used to head up the Interactive department at the Tribeca Film Institute, I still program VR and interactive work for Storyscapes at the Tribeca Film Festival and I currently run a small non-profit funding and supporting VR creators across Africa. Like many of the people I interviewed for this piece, I am simultaneously hopeful and skeptical when it comes to questions around VR and access.

What do I mean by access? Who gets to both make (and make again and again) and experience VR work. The nationalistic and fascist movements sweeping the US and Europe scare the bejeezus out of me and sometimes these questions feel like the very least of our problems. I have to constantly remind myself why art is important and why it is vital that more people have access to emerging storytelling mediums such as VR so that the stories that we are telling and experiencing are diverse, brave and resonant.

This is a really difficult piece to write because I am acutely aware that as a white woman living in Cape Town (a massively segregated city in a country experiencing seismic shifts in post-liberation politics), I am writing from a place of both great privilege and limited perspective. Of course, everyone has a limited perspective to some extent — but some people benefit from this limited perspective while others bear the brunt of its negative effects.

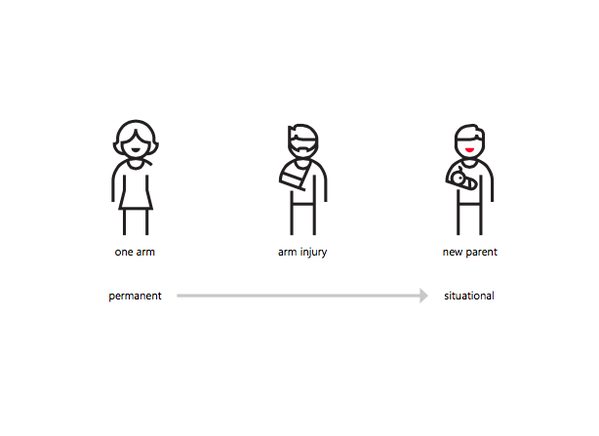

Sundance Institute’s Kamal Sinclair spoke to us over Skype during our recent New Dimensions VR Lab for African artists, which was supported by JustFilms/Ford Foundation and Bertha Foundation. She talked about the blind spots that we will inevitably have if we do not have diverse participation in any field, if it is only the engineers who get to decide the future, for example. Of course, it’s not just engineers. We all have blind spots, which is why we need diversity to be more than just an afterthought, more than just a word companies use to get out of hot water — and diversity, not just of race and gender, but of experience (including age and disabilities) and expertise is critical. I used to keep the image below on my desk to remind me why it is so important to be truly inclusive when you are designing anything, from a building to a new product or a grants program.

“We need to democratize the imagination of our future,” Sinclair argues in a recent piece for the World Economic Forum. She says we are effectively writing the new operating system for the Fourth Industrial Revolution and that “Building a system of inclusion through emerging media that allows a diversity of people to write the code of this next operating system is a critical part of how we mitigate our blind spots and optimize our future.”

This is an important conversation to have, despite the difficulty of approaching such a knotty and complicated topic, and I welcome comments and criticism as I attempt to unravel some of these issues. If you have suggestions for tools, communities or other resources that are relevant to these issues, please do get in touch too. You can use the comment section at the end of this piece or email us at editor@immerse.news. Part of the point of addressing this topic is to see who is out there thinking about these issues and doing good work.

Encountering the barriers firsthand

I spend much of my working life thinking about art, community and what gets valued — and all this channels into strategies around how to be a better field builder. I moved from NYC to Cape Town in 2015 and soon after set up Electric South, a non-profit VR and interactive incubator for African artists, with Steven Markovitz, a South African producer.

I was getting really fed up with many of the VR stories I was seeing covering Africa as I was curating VR work for various exhibitions and festivals. Lots of familiar negative Africa-is-a-country tropes were showing up in VR: poverty, famine, war and disease, you know the drill.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about I highly recommend reading Binyavanga Wainana’s “How To Write About Africa.” It’s not that all the VR works covering Africa were bad, they were the usual mix. Some were beautifully made, and, of course, there are undeniably lots of big problems that make for important stories on this continent. The problem is there is no balance in the African narrative being told—the pieces were all made by people from North America and Europe and they were not telling the whole story.

There is nothing wrong with telling stories about other places. This comes from the curiosity, wonder, concern and joy that brought me to documentaries in the first place. It’s the lack of balance that bothers me. Stories seem to flow in one direction only and it also cannot be denied that as Keren Weizberg writes “Africa has often served as a laboratory of self-discovery for privileged outsiders.” (This is from an online publication called Africa Is A Country, which is worth bookmarking.)

I could not bear to see this being replicated in a new medium about which I felt pretty excited at the time. As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie points out in her well known TED talk, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

Let This Be

A Warning — The Nest, Produced by Electric South

Let This Be

A Warning — The Nest, Produced by Electric SouthAttempting to incubate and fund VR across Africa* has been hugely challenging and has brought many questions around VR, access and inclusion to the fore. Many of these challenges will be familiar but I think some of them are particular to working in a new medium outside of the usual centers of activity:

- It’s considerably harder and more expensive to buy equipment here.

- It’s hard to get equipment in and out of countries when you’re working with artists spread across the continent.

- Visas for African artists who need to travel are expensive and often difficult and/or slow to get. It is often easier for non-Africans to travel across borders in Africa.

- There is not a big community of other people working in the same field to talk to and share resources with.

- The distribution channels and the barriers for consumers are more complicated. Most people do not have access to VR-ready smartphones and good wifi/enough mobile data, let alone the monster computers with the latest graphics cards you need to run a Vive or a Rift.

- There is less local money for the arts available and from a less diverse range of pots. Everyone is going after the same international grants aimed or open to African artists and organizations, which often makes people less collaborative. (I was not aware of quite how much NYC is an all boats rise kind of place until I left it.)

What there is here is a huge amount of talent, ingenuity and leapfrog thinking. Here’s a great example of leapfrogging: in many places in Africa there are bad roads, few landlines and a lot of people don’t have bank accounts or can’t get to their banks or ATMs easily. No problem, Kenya got ahead of the mobile banking revolution with a tool like M-Pesa, a mobile phone-based, branchless banking service.

It is endlessly inspiring to work in a context where things are not easy but where great art gets created, and where innovation is rife. Just check out Fak’ugesi, African Digital Art, Design Indaba, OkayAfrica, Between 10and5, The Nest Collective, Afrofuturism in all its many guises, the joyfulness of Wanuri Kahiu’s idea of AfroBubbleGum, even more bubblegum themes in South African youth culture focused Bubblegum Club and the amazing art glasses made by Cyrus Kiburu, who someone really ought to partner with to create special edition VR goggles.

At our recent New Dimensions VR Lab, one of the artists from Malawi, a writer called Rodney Likaku, commented on how different American dystopic visions are from Afrofuturism. “You have Hunger Games,” he said. “We have hope.”

Cyrus

Kabiru

Cyrus

KabiruUltimately, my questions relating to VR have coalesced around these broad areas:

- Access to networks

- Access to funding

- Access to knowledge and training

- Access to tools, software and hardware

- Access to audiences and markets

Access to Networks

I include access to networks as its own category because it is clear that in addition to financial capital, the cultural and creative capital you can tap into for support is a huge and often under-explored part of what empowers artists to make work and to build careers.

A lot of this capital comes from networks, which replicate themselves over the years through college networks, unpaid internships and other harmless-seeming structures which often ensure that certain groups are never really included, supported or mentored into leadership positions. This is a problem because, while there many awesome, passionate people in leadership and gatekeeper positions in the arts and the nonprofit world, there are nevertheless perspectives that are essentially excluded.

Experience producer Katy Newton made a great point about how it felt to attend a refreshingly diverse conference: “It was easier to talk and listen because everyone didn’t have one voice. You don’t feel the pressure to use one voice, to replicate.” People tell me they love the Allied Media Conference for the same reason. I think the danger in the non-profit and arts world that many of us inhabit is that we pride ourselves on our openness and progressiveness but we often speak with one voice.

We are also often geography snobs, so it is gratifying to see a big push to pay more attention to local media efforts. As Wendy Levy from The Alliance notes, “it’s important to provide access and build community at the local level.” The Trump election was a wake up call for many people around this issue. There was a sense that the media elites on the coasts had either mocked or ignored the rest of the country. The cracks in the country were not created by the media (cough, neoliberalism) but it is certainly true that the media had missed the story and many of us were not paying attention to places outside of the usual arts/innovation hubs.

Access to funding

A lot of people I spoke to made the point that because VR is driven by the technology companies, there is a prioritizing of scale without investment in content. Many of the philanthropic funders are playing the wait-and-see game, so there is not much support in that sector for VR projects yet. As Fledgling Fund’s Diana Barrett pointed out in a piece for Immerse, “The landscape is changing from day to day. Rumors of what might come can paralyze both storytellers and funders, with perfection becoming the enemy of the good.”

As for non-profit arts organizations, many of them are arguing that what they really need is operational funding rather than program funding. This would enable them to be more sustainable and do more long-term planning rather than scrambling to piece together small grants throughout the year for projects that may not be core to the mission of the organization. There is also a call for more nimble funding that responds to the needs of the organizations seeking funding, as well as changing circumstances and political crises.

There is a real push to get more women and people of color into the VR space—but a lot of those artists are not being supported financially. This has already created a growing resource divide. As advisor, teacher and all-round-badass Adaora Udoji points out, “there is a lot of money out there for VR but it’s very opaque.” You need to be super-connected to get access to that money. “We have a window now to keep this space open and diverse,” she says, “You can’t erase challenges but you can mitigate them.”

Udoji goes on to say that everything is moving both fast and slow at the moment, but that we have to act now to make sure that VR becomes the open space so many of us hope it will be. IDFA DocLab’s Caspar Sonnen puts it this way, “There is so much low-hanging fruit in terms of improving the situation in a new medium, but everyone in the field is out of their comfort zone, so we miss a lot of opportunities. We need to talk less and do more.”

Filmmaker Kat Cizek adds, funders considering the VR space “need to explore the medium despite skepticism. Put money and support into inclusive projects. It carves the digital divide further if we don’t. There is a possibility it could become a medium for othering, a playground for the one percent.”

Access to knowledge and training

There are some really great groups online to help people find the resources they need. I have found the Women in VR Facebook group very useful and supportive for example. It is important, however, not to assume that just because resources and communities can be found online, that these will automatically make everyone feel welcome.

As Kenyan artist Ng’endo Mukii, who made a VR piece called Nairobi Berries with Electric South, notes, “confidence is very important and just telling people that they can find tutorials online is not enough.” This is often even more so the case for women, who do not always feel welcome online or face outright harassment in tech and gaming communities in particular. Levy underscores how vital it is to get people connected and make them feel welcome and supported now while things are still in flux, “Give artists all possibilities. There’s no on-ramp right now.”

Sonnen talks about the particular challenges around access in the interactive space more generally:

We’re aren’t one community, we’re not connected by a particular device or mode of consumption. We are not connected by an institution. The community is not defined at all. Where do you find the students, the new talent then? It could be ITP but it could also be journalism school, art school, film school, design school, humanities in general etc. We’re defined by being undefinable. This makes it difficult to create more channels for access. There is no one thing to point to, but there is also a lot of opportunity, so many places that people can emerge from.

Access to tools, software and hardware

Kathy Bisbee runs the Public VR Lab launched by the Brookline Interactive Group and Northampton Community Television. She is deeply committed to VR in the public interest, inspired by George Stoney’s legacy. She has a background working in bridging the digital divide and sees media as a community organizing strategy.

Bisbee notes the wait-and-see aspect of VR, but says she is thinking hard about how to use this time really well until broad consumption arrives. In this she echoes Levy’s sentiment, “We have to keep moving forward, embracing what’s new and building what we need ourselves.”

VR hardware and software is often expensive and requires lots of specialist gear. Because the field is so new, everything is constantly changing, there are endless iterations of both hardware and software to keep on top of. The latest expensive headset or phone can become dated within a year. Or you can spend weeks learning a complicated stitching program only to have a self-stitching algorithm come along to do the job much better.

Here in South Africa, we pay even more to get equipment shipped over and pay customs. We’re earning Rands and paying extra Dollars. It sucks. Most individual artists can’t afford to keep buying equipment that becomes obsolescent so quickly but if they don’t they will be left out of this important prototyping phase, where the field is still so wide open. That’s why centers such as the Public VR Lab are so important, providing access to tools and training for everyone who needs them. This is also why I believe it is so important that African artists are involved now, even if the market is not ready. If we’re prototyping for the future of VR and what comes next then what does it mean if so many people and places are not represented?

The Other

Dakar — Selly Raby Kane, produced by Electric South

The Other

Dakar — Selly Raby Kane, produced by Electric SouthBrian Chirls is working on WebVR with Datavized. He’s excited about many of the tools being created to make VR more accessible but points out that “Every technology carries with it its own culture and its own biases. There’s no drag and drop for weird stuff but you can make a first-person shooter with a module in Unity. What are you freezing in time when you create tools?”

Chirls goes on to say that people should stop expecting great tools to make it easy to create great work. “Accessible tools are not about making it easy to do but about making it easy to get started, much like a word processor.” Having access to a word processor does not automatically make you a good writer and does not solve all the problems around support and distribution for the work that you create. Tools are great and can be democratizing but just because the tools are available does not mean that we have solved access issues.

This is a long way of saying that the there’s-an-app-for-that approach is not going to solve access issues in VR, although I am very excited about the potential for tools such as WebVR. Cizek is also excited about WebVR but acknowledges that right now, it just doesn’t offer enough at an accessible level, noting that “WebVR could be the Robin Hood of the VR world but it’s still very limited.”

Like Chirls, Sonnen talked about the biases inherent in technologies: “VR isn’t that special. It’s an amazing new medium but it doesn’t exist in a void. Every problem we have, VR inherits.” The gaming narrative is pervasive and bias is replicated. “It’s very hard to shift the narrative,” adds Cizek, “There’s an exclusivity to VR. What happened to the democratic principles of interactive?” It’s no wonder then that some people feel excluded in VR. How do we move forward?

“Firstly, everyone needs to calm down and get off the hype machine,” says Sonnen, “We need to understand things by looking at other things rather than trying to predict the future. By pretending and persisting we actually learn.” Newton echoes this call for a more chill approach, “Rapid protoyping is fine, but in this moment we need to slow down and be able to say, ‘I don’t know,’ not over-promise.”

Access to audiences and markets

As artist and Collisions director Lynette Wallworth points out about her approach to her art, “The work is not complete without the viewer.”

There are a lot of unknowns in the VR distribution space. Consumers are not buying headsets in droves, the numbers are below predictions. There’s a great deal of experimentation in terms of audiences, much of it good and necessary but, as Newton points out, “Throwing spaghetti at the audience to see what sticks means you are not respecting the audience.”

More and more festivals are showing VR work. Venice has an entire island devoted to VR this year. Mukii wants festivals and exhibitors to think harder about how to involve the artists: “How do you create special experiences for VR exhibition where the artists feels involved and valued?” What’s the red carpet and Q&A experience for VR artists?

There’s also a degree of exclusiveness to VR exhibition. The more exclusive it gets, the more tantalizing it becomes. Just take a look at exhibitions with limited slots, for example, or people clamoring to get tickets for something such as Carne y Arena, the VR project by Alejandro González Iñárritu. Carne y Arena premiered at Cannes and is now on show at LACMA and sold out until mid-November.

In terms of distribution, access is a very obvious challenge. As Jessica Brillhart—until recently the principal filmmaker for VR at Google and one of the finest thinkers on the craft of 360—argues, the people who could really use VR will probably be the last people to get it. Distribution is complicated for everyone, but doubly complicated in Africa, where many of the headsets are not readily available and only a small proportion of the population have VR-ready smartphones and affordable data.

Cizek is excited about the exhibition and creative opportunities afforded by museums. VR needs a context, a container, she says, and museums can be a great space for this. “VR is more tethered to a physical reality than any other medium in the last 50 years. We need to understand this for storytelling,” she says. She’s also worried about how non-fiction VR work will get to audiences. Documentary often makes an impact through educational systems, but this doesn’t work in VR. School boards won’t buy headsets en masse.

We did a couple of VR exhibitions at the Central Library in Cape Town for the Encounters Documentary Festival and it was really cool to see how a space like a library creates different expectations for audiences. Libraries are open and welcoming by design and we got a really interesting mix of attendees. What kinds of spaces are you choosing or creating for VR exhibition and how does this affect who feels welcome in those spaces?

Virtual

Encounters exhibition at the Cape Town Central Library, June 2017

Virtual

Encounters exhibition at the Cape Town Central Library, June 2017So what now?

This stuff keeps me up at night. I know VR won’t stick around as it currently exists, but immersive storytelling is not going away. Augmented Reality (AR) and whatever comes next will continue to change our expectations about how we experience stories, art, therapy, education and training.

We will continue to exist in an immersive, XR world, that much I am fairly sure of. This is why it is so important that we tackle these issues now, before things become ossified, before people with power close ranks. Things are moving both fast and slow.

I get really nervous when I read slightly gleeful pieces about the coming Fourth Industrial Revolution. We are people, not inputs. We have inalienable rights and untapped potential. The robots may be coming—but I’m still working in an environment where a lot of people don’t have access to electricity and running water. We need to hold all these truths in our heads at the same time in order to move forward.

As adrienne maree brown put it in an article in Immerse last year, “This is the moment for visionary narratives”:

Now we need to be the storytellers of the next phase of the future. And we need to concern ourselves not just with the content of our liberating imaginings, but with how we will imagine together.…This has to be an exciting time. Our work as creatives, filmmakers, activists, and storytellers, is to answer Toni Cade Bambara’s call “to make the revolution irresistible” and, I would argue, to sustain us when the odds don’t appear to be in our favor. We must deploy every tool in the box for the sake of ourselves and future generations.

I do despair sometimes, especially at 3:00 am, when I wonder what the hell I was thinking starting a non-profit to jump-start creative VR in a country I had only just moved back to. There are so many other things I could be doing, things that might feel more useful, more practical. But I want to carve out a space for collaborative making that is not limited to what the market will support—which right now looks like property tours and safari videos. There’s nothing wrong with either of these things but it’s not what I want to spend my time working on and I don’t believe that what the market supports is enough, for any of us.

This is a call for more field builders, funders, companies and artists to join the fray, but it’s also a call for those of us in positions of power, however small they may be, to create space for other voices and perspectives so that in ten years we can look back at this time and say “Yay, look what we did!” rather than, “Oh god, what have we done!”

I know Africa has 55 countries and I am doing massive disservice to the diversity of the continent when I talk about Africa as a whole but our Electric South initiative does cover the whole continent and in order to get through this piece I am going to have to keep doing this!

An Immerse response: Who Is VR For? Maybe for Me and My Mom

Many thanks to everyone who talked to me while I researched this article: Wendy Levy, Kathy Bisbee, Brian Chirls, Kat Cizek, Ng’endo Mukii, Jim Chuchu, Adaora Udoji, Katy Newton and Caspar Sonnen — and to all the artists and advisors and speakers at the recent New Dimensions VR Lab in South Africa who gave me so many ideas and so much hope.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.