Personal

reconstruction of dust on garden vision

Personal

reconstruction of dust on garden visionWhen I was around 9 years old, I was walking in a garden similar to the one on this picture when I noticed a strange black spot moving down in an awkward place in the sky. I found this deeply disturbing: I knew it was not an object in the sky, so it had to be in my eyes. It took me half a second to figure out that I had a slight impurity, maybe just some dust, moving down the right side of my right eye.

That was a moment of revelation.

Until that day the world was as I was seeing it, no doubt. But now I could see the landscape with a black blob on it, and I knew the blob was not “out there,” so my eyes were tricking my perception of reality. A terrible doubt crossed my mind: could I ever be sure of what the world “really” looks like?

photo by

S.Gaudenzi

photo by

S.GaudenziI grew up in a bilingual family — mum was French and dad, Italian.

At a very early age, my mind got used to knowing that a glass is not a glass.

A glass is a “verre” in French, un “bicchiere” in Italian and a “glass” in English. Words are not things, they are our way to make sense of things. They say as much about us (where we come from, our social background) than about the “thing” itself.

photo by

S.Gaudenzi

photo by

S.GaudenziIt might have been my upbringing, it might have been my character, but I grew up to see the world as a complex place, a world of diversity in which one language is not more “true” than the other, where a glass can be called and used differently, a place where a glass is the result of multiple uses and cultures, hence not a single, fixed thing.

Gaining perspective

Do you remember this? The Powers of Ten (1977), by Eames Office.

It used to, and still does, fascinate me.

But while as a young girl I saw magic in it, I now relate the gap between the infinitively small and big to the words of biologist Richard Dawkins. In a great 2005 TED Talk, he describes how our human frame of reference limits our understanding of the universe. Our human perception and understanding is shaped and limited by our physical existence in what he calls the “Middle World.” The Middle World, he says, “is a narrow range of reality on which we judge to be normal, as opposed to the queerness of the very small, the very large and the very fast.”

For me, The Powers of Ten (1977) resonated as a fundamental way of understanding the world: nothing is universally true or false, everything is relative to scale, time and context, and depends on the eyes of its observer. Years later, I ended up writing a whole PhD linking second wave cybernetics (Maturana and Varela and their concept of autopoiesis) with the way digital interactive narratives could place the user inside, and in dialogue, with the story-world to co-create reality with the author and the digital medium.

My resistance to see the world as fixed, as an either/or black/white place, is one of the reasons for which I have a big problem with Trump and Brexit today.

The best way I have to make sense of both is to see them as the result of accumulated fear emerging from a prolonged Western economic crisis. I understand the fear of the unknown, I totally respect that. I also understand why people would want to defend what they have built during their lives. But what I do not understand is the rhetoric that claims that isolation and rejection of diversity might be a solution. A single point of view, for me, is never the solution. It is just a lie. It would be like saying that the world has dust on it just because I have a blob of dust inside my right eye. The world is the result of all of our points of view. The world is complex.

A single point of view, for me, is never the solution.

This is where digital media and the internet can help us to express a complexity more akin to the truth.

Revealing multiplicity

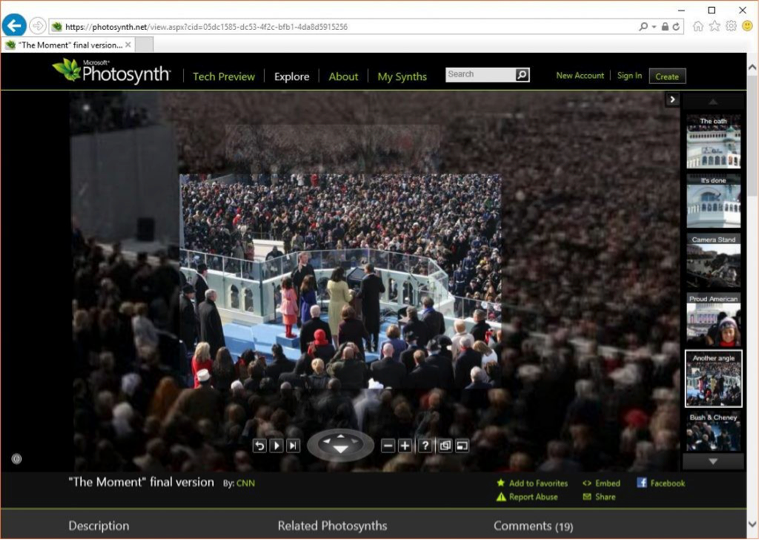

The significance of Obama’s first speech as a newly elected President in 2008 could not be encapsulated by a single broadcast recording. It was the way that such a speech resonated across the homes of the United States, if not the world, that created “The moment.”

“The

Moment”, Photosynth & CNN, 2008

“The

Moment”, Photosynth & CNN, 2008The then-revolutionary Photosynth software allowed such complexity to become visible. The possibility to catch a moment in time within its pluri-cultural and layered contexts, and not through our limited individual eyes, is something we can aim for when using digital media.

If used this way, digital media matters. Instead of putting us in the position of the observer—the photographer, the camera person, the broadcaster, who is always defending one point of view through selective framing—the internet is plural by default. It can use multiple links to show us our co-existence in real time. More: the web changes as we change, speaking through flow rather than stillness. Digital media speaks of a shared world — at least this is what it could do so much better than linear media.

The internet is plural by default

For me, this is why telling stories with digital media is a way to speak of the world through a medium that respects the way we understand and create the world: through interactivity, constant feed-back and context-learning. It is a way to avoid the trap of single causality that dominates the linear world. It is a way to fight back against the simplistic causalities used lately by politicians looking for affective rhetoric.

Respect for plurality and neutrality is one of the internet promises that we are in danger of losing. Tim Berners Lee’s open letter to defend web neutrality after receiving the Turing Award, and the three recent books that have come out about post-truth that are reviewed in this article from The Guardian are here to remind us that this is a time to fight back. If we don’t, we will be the first to lose—and we will lose big time.

We need to fight for digital platforms that are based on the values we want to defend: inclusion and multiplicity rather than manipulation.

Telling stories that defend our values

One way to fight is to create more stories that use software to counteract the current social media tendencies. Projects such as Do Not Track and Digital Me are clearly going in that direction. They use personalization and data mining to give back the power to the people that own the data — in other words, us.

Do Not

Track, 2015

Do Not

Track, 2015Echoing Patty Zimmermann and Dale Hudson’s book, I believe we need to start “Thinking Through Digital Media” in order to shape our digital sphere back into a space that fosters our beliefs. This will then have an effect on our economic and political world. This is why interactive stories matter.

When polyphonic music replaced homophonic chant in the early renaissance, music gained in strength, beauty, complexity and emotional expression. But more importantly, by moving from a single to a multi-melodic harmony, musicians were expressing a view of the world where humans, rather than the single God of the Middle Ages, wanted to have a voice.

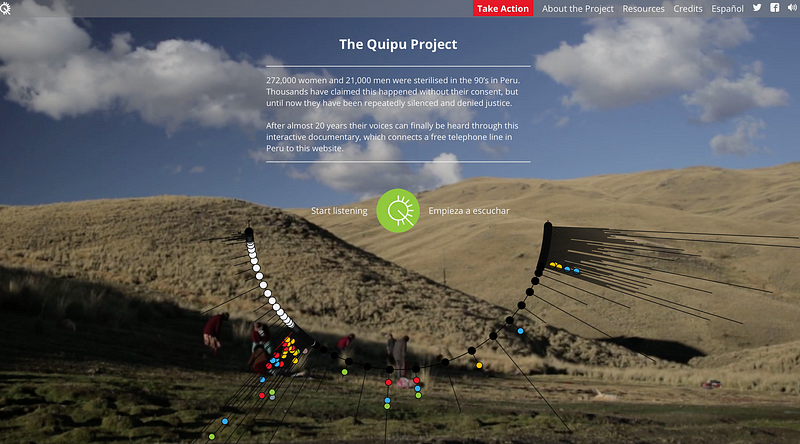

Projects such as Quipu, Living Los Sures, Highrise, and most collaborative i-docs are stories co-created by several voices. They are the polyphony of our time.

The Quipu

Project, 2015

The Quipu

Project, 2015When we hear them we are placed inside, we have a role. This is another affordance of digital media that is worth fighting for: the possibility to move from “listeners” to “doers.” In traditional linear storytelling the hidden contract between the author and the audience is “I will tell you a story. Listen to it, then decide what you want to do with it.”

The same happens in traditional education: first listen to the teacher, and put it in practice through an exercise (or repeat for an exam). You first receive, then maybe act. But this is a construct of society and media power. Our natural way to perceive the world is to react while we are perceiving. It is through a constant loop of action-reaction-perception that we learn to walk. No one can learn to walk without confronting the world through action (as a famous experiment with kittens, led by Held and Hein, has proved in 1963).

Our natural way to perceive the world is to react while we are perceiving.

The chance, the opportunity in interactive storytelling is merging the doing/learning/thinking in the same space. It is about building places that resemble the way we exist in the world every day: through embodied interaction — through reacting, changing, elaborating as we go along. This is true in web-based docs, but even more in VR, AR and locative stories.

In order to learn through interaction we need to step out of our simplistic notion of digital interactivity as “click and link.” We also need to switch our authorial model and move from being narrators to becoming architects — makers of spaces for others to explore and be transformed by. We need to create spaces of action, spaces of expansion, of opening and discovery, spaces that move toward the transition we want for our world.

To my knowledge, this is where most institutions are getting cold feet. Legacy media (newspapers and broadcasters) are scared of to make radical digital decisions and move towards new paradigms of journalism and storytelling.

Universities too tend to protect their faculty silos and move slowly towards a disruptive multi-disciplinary approach that puts in peril their current way of working. These are changes that will take time as they mean radical power shifts and need internal reorganization.

I stay convinced that radical change is essential if we want to feel re-empowered. Some digital agencies are doing amazing work, a few newspapers (the pioneers, The New York Times and The Guardian come to mind) are taking some digital risks, and a few universities are opening new courses and labs to step into the new paradigm (MIT and Columbia University, of course, but I am also thinking of the new disLAB MA I am co-launching at the University of Westminster).

We live in blurry times that can make us feel powerless. And yet, if we could remember that the dust in our eyes can be scary at first, but then leads to the realization that we are responsible for the way we interpret and act in the world… then things are possible again.

The world I want for myself and my children is a world full of colourful glasses, where we recognize and welcome other people’s definitions, uses and memories of what a “glass,” a “bicchiere,” or a “verre,” might be…

photo by

S.Gaudenzi

photo by

S.GaudenziThis piece by Sandra Gaudenzi is the lead story for issue #10 of Immerse, which was curated by the editors of i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary (Columbia University Press, 2017). Discover other stories in this issue here.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.