On the historic link between immersive media and fascist propaganda

Is immersive — media that “occupies

most of one’s attention, time, or energy” — a quality creators should be striving for? (Photo: Andri Koolme)

Is immersive — media that “occupies

most of one’s attention, time, or energy” — a quality creators should be striving for? (Photo: Andri Koolme)When news outlets started buzzing about Facebook’s new Oculus 2 headset this fall, I mentally blocked out the headlines. Whatever you think of Facebook, it is one of the world’s leaders in psychological profiling, data-mining, and precision-targeted propaganda. And it’s leading the charge toward immersive.

After four years working as an editor of Immerse, I feel that it’s time to ask: Why do so many well-intended makers seek to create immersive media? I’m not talking about any specific media platform (VR, AR, XR) but the quality of immersiveness itself — immersive in the sense of “digital technology or images that actively engage one’s senses and may create an altered mental state” (Dictionary.com) or a “deep absorption or immersion in something” (Merriam-Webster).

By these definitions, a 12-hour anime binge is, arguably, an immersive experience.

Reclining on the couch so fixated on YouTube that you miss your friend’s calls could be considered immersive.

Scientology is immersive. So is drowning.

Forgetting one’s surroundings, losing track of physical reality, and escaping into a constructed world — are these in themselves a good thing?

As the parent of a middle schooler during a global pandemic, I can’t help but see a lot of downsides to immersive. “Immersive,” for those of us raising humans whose brain parts and wiring aren’t all there yet — is easy to confuse with “compulsive” and even “addictive.” Teens are spending hours every day on social media, mostly on smartphones and tablets. If small, handheld devices without a lot of high-tech sensory outputs are so consuming, what impact would surround-sound headgear, a more robust sensory experience, and increasingly personalized, psychologically targeted content have?

Algorithm-based platforms (not only Facebook but YouTube, Twitter, TikTok, and others) are engineered to grab and to hold users’ attention, to immerse them in the platform. When these outlets cater to inflammatory content, fear-mongering, misinformation, political discord and hate, they are doing what they are intended to do. It’s by design — a feature, not a bug. These platforms don’t necessarily have a particular political agenda beyond making money. It just so happens that prioritizing user engagement and homogeneous user-bases is a profit model that provides the pipes for Al-Shabaab and other terrorist groups to recruit, for pitting Latinx communities in Florida against Black Lives Matter (and scaring them away from voting), and for promoting white nationalism and violence. The New York Times podcast “Rabbit Hole” documents how algorithm-based media platforms lead even normal, healthy adults down filter bubbles toward racial extremism, body dysmorphia, anti-science, and all manner of misinformation.

So, after four years of reading VR stories here, I’d urge our readers to seriously consider this question: How are makers of VR, AR, and other emerging forms defining the kind of immersion they wish to create — and how can these makers intentionally, proactively, deliberately avoid feeding the dangers?

I’ve attended a number of VR events where journalists bemoan the inaccessibility of headsets and the small size of the audience. To those complaints, I mumble to myself, “Thank god.” How much time would teens spend on THAT? Before we let Facebook and Google provide the pipes for enveloping sensory experiences, we need a full-on media ecology reboot; we need substantial media reform.

Produced in 1943 by the US

federal government, “Don’t Be a Sucker” was deliberately crafted to avoid the immersive, emotionally

manipulative techniques that progressives associated with fascist propaganda.

Produced in 1943 by the US

federal government, “Don’t Be a Sucker” was deliberately crafted to avoid the immersive, emotionally

manipulative techniques that progressives associated with fascist propaganda.Shortly after white supremacists marched in Charlotte in 2017, a short film by the US Department of Defense from the 1940s started circulating on social media. The Committee for National Morale, which advised President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on media policy, created the film “Don’t Be a Sucker” as part of an effort to counter Nazi propaganda.

The task that FDR faced in using media to fight propaganda was, naturally, fraught. One camp of advisors saw the effectiveness of the Nazi’s manipulative techniques and wanted to copy them — to fight fire with fire. But anthropologist Margaret Mead, along with other progressive thinkers who made up the Committee for National Morale, won out with a different approach: they went to lengths to avoid replicating what they saw as core tools of authoritarianism and fascism.

Yes, the government needed a persuasive media strategy, they said. Yes, they needed American unity in order to combat the global threat of fascism. But what they did not need — and what they considered counter to a humanistic, democratic approach — was “immersive” media. Mead and her colleagues realized that while uniting citizens around a cause was urgent, it must not come at the expense of individuality. It must continually allow and encourage citizens to pause and reflect.

As a result, “Don’t Be a Sucker” is minimalist in its approach, even for its time. There is no narration, no inspiring or emotional music. Instead, the film very simply captures a conversation between two white men talking to each other about things that unite and divide:

[Man 1]: I’ve heard this kind of [hate talk] before, but I’d never expected to hear it in America…

[Man 2]: I don’t know. It’s pretty good sense to me. What about you? You are an American, right?

[Man 1]: I was born in Hungary, but now I’m an American citizen… In this country, we all belong to minority groups. I was born in Hungary. You are a Mason. These are minorities. And you belong to other minority groups, too. You are a farmer. You have blue eyes. You go to the Methodist Church. You have a right to belong to these minorities. It is a precious thing…

Stanford University historian Fred Turner documented this point in time — and the planning behind this campaign — in his pioneering history The Democratic Sound: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties. In the book, Turner writes,

“Abraham Maslow spoke for many when he wrote, “The democratic person . . . tends (in the pure case) to respect other human beings in a very basic fashion as different from each other, rather than better or worse. He is more willing to allow for their own tastes, goals, and personal autonomy so long as no one else is hurt thereby.”

Mead and her colleagues were channeling Maslow in their approach, reminding viewers of their individuality, of their differences, and the need to recognize and experience other points of view. Democratic media, Maslow and these thinkers believed, needed to do two things:

a) Portray and prioritize diversity, by which they meant respect for others’ views and experiences, even those you don’t personally agree with or like.

b) Avoid occupying all of someone’s attention — building in breaks and ensuring audiences remained aware of their individuality and their environment… in other words, avoid being immersive.

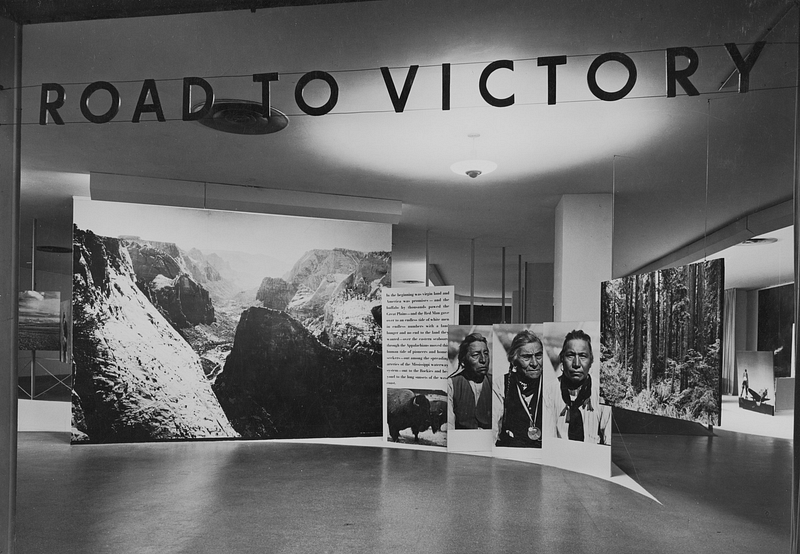

Funded by the United States

government to united Americans during World War II, The Road to Victory (1942) by Herbert Bayer at

the Museum of Modern Art was hailed as the pinnacle of an immersive exhibit in its time. But, according to

historian Fred Turner, the exhibit’s creators aimed for visitors to retain a strong sense of

their own identity while feeling the emotional tug of giant photographs: “The people who designed

these surrounds were very conscious of making sure that there was physical space between images, so

that there was room for a person to recover themselves after engaging with the information, the

picture, or the data.” (Photo: MoMA)

Funded by the United States

government to united Americans during World War II, The Road to Victory (1942) by Herbert Bayer at

the Museum of Modern Art was hailed as the pinnacle of an immersive exhibit in its time. But, according to

historian Fred Turner, the exhibit’s creators aimed for visitors to retain a strong sense of

their own identity while feeling the emotional tug of giant photographs: “The people who designed

these surrounds were very conscious of making sure that there was physical space between images, so

that there was room for a person to recover themselves after engaging with the information, the

picture, or the data.” (Photo: MoMA)In 1991, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission mandated that children’s television programs build in breaks to provide children opportunities to get up, check their surroundings, and stop watching. Such regulations no longer matter, now that the biggest content provider of children’s content is YouTube, and the sources of internet content are seemingly infinite. It seems quaint to think back to the 1950s, when the major media networks needed to adhere to a Fairness Doctrine, requiring that opposing points of view on any political controversy receive fair and balanced time.

VR producers showing at festivals and events can’t help but notice how difficult it is for some participants to emotionally self-regulate after emerging from a “successful” production. Sometimes they’ll need 15 minutes to sit, decompress, cry. Is this kind of deep involvement with a piece a good thing? Can such emotional manipulation be dangerous?

My guess is that those of you reading would say “yes.” Here in the US, we like to view technology as neutral — whether we’re talking about guns, or gene therapy, TV, or VR, we like to believe that the tech isn’t itself good or bad, it can simply be put to both good and bad uses. What this line of thought fails to recognize is that some people will be able to take more advantage of a tool than others. If VR can be used to portray the treacherous path to an abortion clinic it can also be used — and with greater funding and resources — to show violent images of unborn fetuses, deepfakes, and other terrifying, anxiety-provoking (“engaging”) content.

The major social media platforms (Facebook, YouTube, Snapchat etc.) provide a model of how this works by maximizing users’ attention at all costs: more violence, more anxiety, and more fear means more “user engagement,” more target-marketing, more dollars. As activist Fadi Quran of Avaaz put it, social media is “skewed to benefit bullies.”

So, for creators of immersive media, perhaps a little soul-searching is overdue. Artists and producers may find it gratifying when a person experiencing their VR or AR exhibit comes out of it shaken, or joyous, or emotionally transformed in some way. Why? What is behind that impulse to shape and mold others? And what can practitioners learn from those stodgy old antifascists who pressed for a media landscape that honors individual differences and autonomy?

ESSENTIAL RESOURCES

“Your Undivided Attention” podcast from The Center for Humane Technology — Episode #23, the interview with Fred Turner, inspired this piece. This organization has been providing essential conversations and posing possible solutions for rethinking media to center humanity.

Anti-Social Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy by Siva Vaidhyanthan (Oxford University Press, 2018). The followup to Vaidhyanathan’s pioneering critique of Google is just as accessible and illuminating. Vaidhyanathan has a knack for synthesizing complex processes and outlining why they matter.

“You Are the Product” by John Lanchester (London Review of Books, August 2017). This review of nonfiction books by Tim Wu, Antonio Garcia Martinez, and Jonathan Taplin is what prompted me to delete my Facebook account three years ago.

“Complicit: The Human Cost of Facebook’s Disregard for Muslim Life” For a well-researched, mind-boggling compendium of how Facebook has amplified religious bigotry around the globe, don’t miss this October 2020 report from Muslim Advocates, which documents Facebook’s support for fascist leaders worldwide.

“Rabbit Hole” podcast. Highly bingeable journalistic series focused on algorithm-based media — most notably YouTube, where otherwise healthy humans have been known to lose all sense of time and purpose when fed a constant stream of ever-“engaging” recommendations. It’s worth noting that these immersive “rabbit holes” or “filter bubbles” reflect homogeneous subpopulations and perspectives. (I saw how potent this force is when I started regularly deleting YouTube watch and search history from my kid’s device; it dramatically shifted their YouTube viewing habits toward more diverse topics, peoples, and opinions.)

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.