Exploring audience responses to virtual reality nonfiction in the home

by Mandy Rose & David Green

Between 2017 and 2020, our interdisciplinary research team explored the potential of virtual reality for documentary within the Virtual Realities: Immersive Documentary Encounters project. Drawing on the traditions of Computer Science, Documentary Studies and Experimental Psychology research, we conducted a series of quantitative and qualitative studies; we created an online mediography which offers a snapshot of the themes, teams and extent of English language VR work between 2012 and 2018; and we commissioned three path-finding VR projects.

In seeking to understand the potential of VR for documentary, audience research was central to our project. Our experimental lab-based studies explored Empathy, Prejudice and Prosocial Behaviour, Viewer Synchrony & Co-Presence, and the effect of user posture on emotional impact in one of the commissions.

We also conducted a major study to explore how audiences experience VR nonfiction in sociocultural context.

A study

participant uses a Viewmaster at home.

A study

participant uses a Viewmaster at home.Exploring audience responses to VR nonfiction in the home

To gain an understanding of how VR might fit into people’s wider media usage, we developed an audience study and engaged a diverse cohort of households from Bristol, UK, to participate in the study. To include the perspectives of participants who are poorly reflected in research into emerging media technology, we worked with two local community organisations; Knowle West Media Centre, an arts centre based in a lower-middle income area of Bristol, and Refugee Women of Bristol, a “multi-ethnic, multi-faith organisation which targets the needs of refugee women in Bristol.”

In partnership with the community organisations, we co-hosted six informal VR experience days where people could drop in and try VR — often for the first time. After following-up with people who showed an interest in the project, to talk through the approach and process, we settled on 12 households; 35 participants; a mixed group socioeconomically, culturally, and in terms of gender and age.

Some of the

study participants, photographed at the beginning of the study.

Some of the

study participants, photographed at the beginning of the study.We gave each household an Oculus Go pre-loaded with 46 pieces of curated VR nonfiction content around eight of the most popular themes (as revealed by our mediography work) — Space, Human Migration, Art & History, World Cultures, among them.

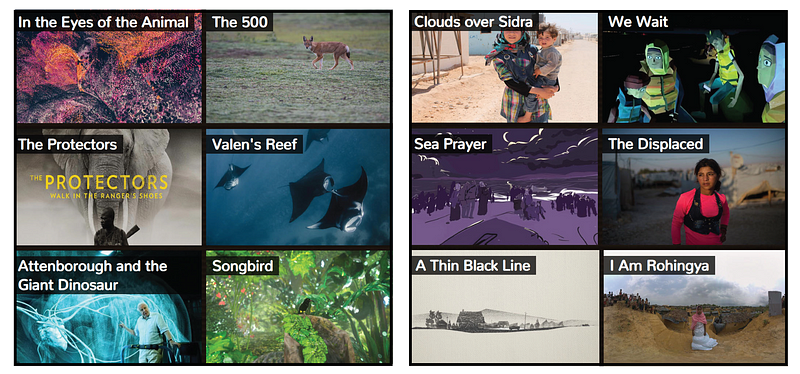

Two of the

eight themes — The Natural World (left) and Human Migration (right)

Two of the

eight themes — The Natural World (left) and Human Migration (right)To gain insights into what participants made of VR beyond their initial impression, and to explore whether they formed any habits in relation to the platform, we spread the study out over several months.

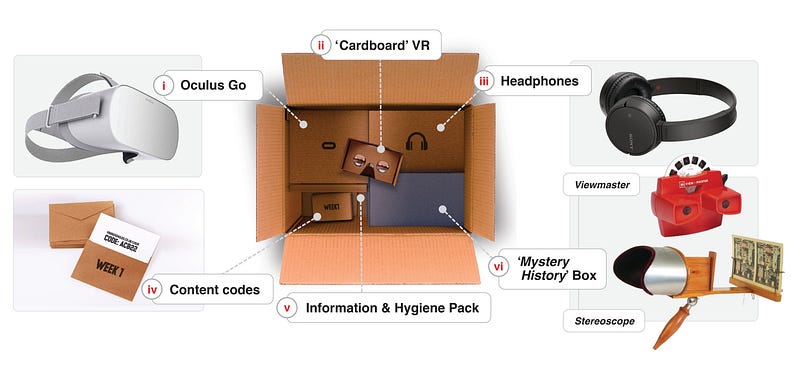

Study

materials, including an Oculus Go.

Study

materials, including an Oculus Go.We talked to participants about their experiences in two in-depth, semi-structured group interviews — the first when we delivered the equipment, another at the end of the study — and we kept in touch with participants via WhatsApp throughout the study, asking questions and prompting them to engage with new content.

Responses to VR nonfiction

Participants from all households, across all demographics, saw positive potential in virtual encounters with real people and places in VR. They made clear connections between the affordances of VR for immersion and presence and their sense of engagement with nonfiction themes.

“It didn’t matter where I went, I felt like I was in it, you know? On Valens Reef I’d find myself holding my breath, because it felt underwater.”

“In the story of water in Pakistan, where the community were gathering outside of their house and they were kind of coming up with different ideas of how to clean the water. You feel — in that moment — you are sitting next to them.”

Participants felt that that their understanding of factual subject matter was enhanced by the feeling of virtual proximity to people and places in VR, and by the perspective taking allowed by 360 degree media.

“I think you get a lot more from VR. Being able to understand the person’s story — like the blind guy in [Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness]… It just gives you more of a sense of what he’s feeling. You wouldn’t get that watching a documentary on a flat screen.”

“VR helps you understand real world problems. You see it from their perspective. You can understand them.”

Research participants made frequent comparisons between VR and TV in which they drew out the value of immersion for conveying a vivid sense of real-world scenes.

“It’s better in VR because you can look up at the buildings, you can see the sky; you can turn around. Whereas you wouldn’t get that watching TV.”

“360° immersion in the rubble somewhere in Syria hits home a lot harder than it does watching on a 48” TV, because it’s all there, around you.”

We were interested to note how the values that participants highlighted in these VR experiences resonated with currents within the documentary tradition — in particular the quality of experience prized within Observational Cinema and which Direct Cinema pioneer Richard Leacock called, the “feeling of being there”.

“In the story of water in Pakistan*, where the community were gathering outside of their house and they were kind of coming up with different ideas of how to clean the water. You feel — in that moment — you are sitting next to them.”

Alongside these positives, participants also expressed a number of pertinent reservations about nonfiction VR. Some had concerns about the emotional and persuasive power of the medium. Others worried that presence had the potential to amplify the impact of distressing or intense content, with implications for vulnerable users.

“I have had to flee… I have had to run for my life. I don’t know if that would trigger a memory.”

“I’d be careful about showing it to people on drugs, or if they’ve got mental illness, because I think it could be very confusing”

Some participants mused about VR’s persuasiveness, and wondered about its potential for manipulation.

“Actually, I trusted the content in the VR more… because I was in it. So I think it could be really persuasive, which is interesting.”

“I suppose — in that it had the potential for a person to empathize more deeply with a subject — that’s like the currency of propaganda.”

Others noticed how, while presence endowed content with a compelling veracity, it also obscured the mediated nature of the content — the director’s choices and point-of-view.

“It’s not the same, because you feel immersed in it — you feel like you’ve been somewhere, and you feel like you know about it; but actually, you just know one person — one filmmaker’s — perspective.”

While they offered these valuable insights, participants also expressed reservations about VR as a medium at home, and demonstrated those through a lack of sustained engagement. Seven out of the twelve households stopped engaging after one or two weeks. For three others, it was a more gradual tapering. Only two households persevered until the end of the study, and they conceded that doing so was out of a sense of duty to the research project. The headset was the problem. Most felt VR to be unsociable when others were at home, and they felt vulnerable if they used it when they were home alone.

More research will be needed to understand immersive media’s potential for nonfiction in a domestic setting. Perhaps augmented or mixed reality platforms might deliver some of what participants valued in VR, without the sense of dislocation from other people and the physical environment. However, participants’ wish for sociality led them to speculate on the potential of VR for social connection. Some wished that they could jointly experience the VR content that was made available within the study. Others mused on VR’s potential for co-presence with others who they were separated from. With Covid-19 enforcing social distancing, and people turning to virtual reality as a platform for connection rather than isolation, their insights take on particular relevance and poignancy, and suggest that sociality ought to be a central concern within future VR nonfiction research and production.

You can read a full analysis of the household study in Convergence (free access):

'You wouldn't get that from watching TV!': Exploring audience responses to virtual reality… Abstract Consumer virtual reality (VR) headsets (e.g. Oculus Go) have brought VR non-fiction (VRNF) within reach of…journals.sagepub.com

Citation: Green DP, Rose M, Bevan C, Farmer H, Cater K, Fraser DS. ‘You wouldn’t get that from watching TV!’: Exploring audience responses to virtual reality non-fiction in the home. Convergence. December 2020. doi:10.1177/1354856520979966

This article is part of Virtual Realities, an Immerse series by researchers on the UK EPSRC funded Virtual Realities; Immersive Documentary Encounters project. This project is employing an interdisciplinary approach to examining the production and user experience of nonfiction virtual reality content. The project team is led by Professor Ki Cater (University of Bristol), Professor Danaë Stanton Fraser (University of Bath) and Professor Mandy Rose (University of the West of England) with researchers Dr. Chris Bevan, Dr. Harry Farmer and Dr David Green and administrative support from Jo Gildersleve.

For more information see http://vrdocumentaryencounters.co.uk.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.